Martin Kuz is too modest for his own good.

Despite producing some of the most insightful and compelling reporting from the Afghan War, it seemingly pains Kuz to talk about himself, even when prompted.

However, his most recent work covering the war in Ukraine puts him in a more talkative mood due to his personal connection to the country’s history of hardships.

Kuz’s late father emigrated from Ukraine in 1955, during the tyranny of the Soviet era and he still has extended family in the country.

He’s been traveling to Ukraine for two years, producing excellent work for Postindustrial, and others.

[Be sure to subscribe to his must-read Ukraine reporting substack]

Kuz took a moment — with some prodding — to discuss his close connection to Ukraine, how it impacts his work, and what he sees in the country’s future.

Postindustrial: Your connection to Ukraine is personal. Does that make covering this war more difficult than the reporting you’ve done in Afghanistan?

Kuz: A little background: My late father, Eugene Kuz, was born to Ukrainian parents in 1923 in Lviv, a city then inside Poland’s borders. Ukraine reabsorbed Lviv after the Soviet Union annexed a large swath of eastern Poland on the eve of WWII in 1939. He immigrated to America in 1955, and I still have relatives in western Ukraine.

In one respect, the family connection has made reporting on this war easier because, from the start, I was more familiar with the country and its history. Also, spending the better part of three years in Afghanistan — the first war I covered — helped prepare me for what to expect when missiles began falling in Ukraine.

The main difference is that this war evokes stronger emotions. I understood the tragedy of Afghans – how they had endured decades of strife and needless suffering dating to the late ’70s, when the Soviets invaded. But my feelings about Ukraine run deeper because of the personal ties. I learned from my father about Russia’s legacy of tyranny against his homeland, and now, only 30 years after Ukraine gained independence, Moscow is once again terrorizing his people. My people. So there’s a persistent sadness — and anger — about what’s happening. That doesn’t make the work more difficult — it serves as motivation to keep sharing Ukraine’s story.

Postindustrial: What are we, at home, and the news media largely missing about the war in Ukraine?

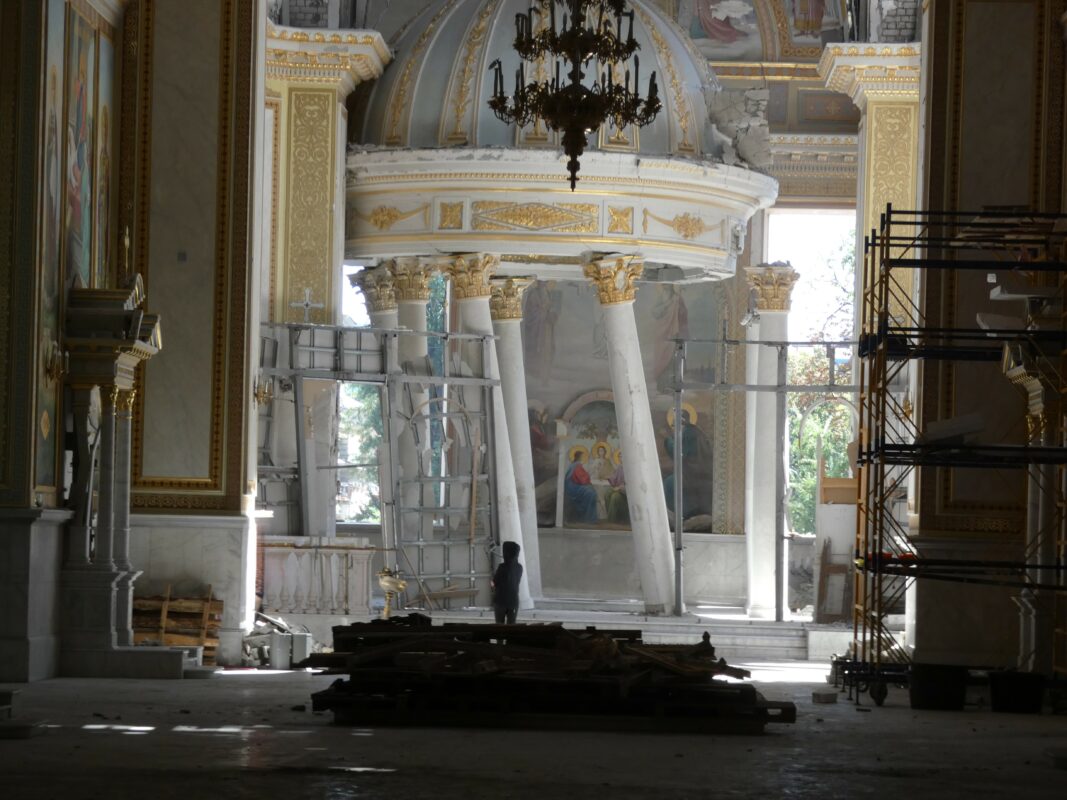

Kuz: One thing that doesn’t fully come across in photos and videos is the sheer vastness of the destruction that Russia has inflicted: houses and apartment towers, museums and churches, middle schools and universities, shopping malls and government buildings, factories and power plants, bridges and dams, roads and train stations. On and on and on. Ukraine is about the size of Texas, and from one end of the country to the other, in villages and cities alike, the ruins are everywhere. The breadth of the damage almost defies imagination, even when you see it in person.

News coverage tends to focus on the latest missile and drone strikes, and that’s the lens through which most Westerners view the war — another day, another attack, pass the chips. They’ve grown numb. After two-plus years of blow-by-blow headlines, most people outside Ukraine have forgotten the horrors in Bucha, Izium, and Mariupol and are oblivious to the war’s relentless daily toll. But Ukrainians will always remember, and the coverage seldom captures that sentiment. So, in the same way that it’s hard to comprehend from afar the scale of the devastation, it can be difficult to grasp the intense defiance that still burns within them.

How intense? A recent poll showed that nearly 90% of Ukrainians believe their country will prevail over Russia. The figure might surprise Westerners. But when you see the destruction all across Ukraine, you begin to understand why its people — no matter how war-weary and bereft — refuse to kneel before Moscow.

Postindustrial: In your estimation, how will this war end?

Kuz: What I want to happen differs from what I think will happen. I want Russian forces pushed out of Ukraine and the country’s 1991 borders restored, which includes Crimea; fast-track NATO and EU membership for Ukraine to avoid a replay of the disastrous agreement that stripped the country of its nuclear weapons in 1994; permanent economic, financial, and trade sanctions imposed on Russia to limit its global influence; and Russian President Vladimir Putin and every last one of his generals, government ministers, and advisers tried before the International Criminal Court.

What I think will happen is something resembling the armistice that ended fighting in Korea in 1953, without achieving full peace. I don’t foresee an Afghanistan scenario where Russian troops capture Kyiv and Ukraine’s government collapses. But Ukrainian forces will struggle to reclaim occupied territory as cracks widen in the Western coalition and isolationist Republicans in Congress block U.S. efforts to fund Ukraine’s military.

Time and numbers — troops, weapons, ammunition reserves — are on Putin’s side, and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky realizes his own options are dwindling. And so, with heavy heart, I envision an agreement that cedes most, or all, of the land in the south and east to Russia that its troops now control, including Crimea; the creation of a demilitarized zone between the illegally annexed regions and “mainland” Ukraine; and the presence of international peacekeeping forces in the DMZ. That last element will be crucial because Putin will violate the armistice before the ink dries.

To learn how you can support Martin’s important work in Ukraine, click here.