The Edgerton Earth, a tiny weekly newspaper in northwest Ohio, is a scrappy, long-serving provider of news for Northwest Ohioans seeking truth … not to mention a full-body bronzing by way of its tanning beds.

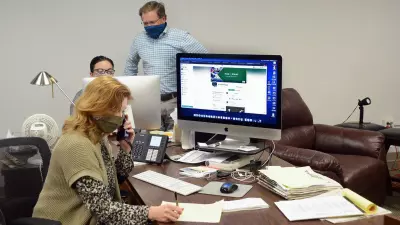

Whether you want to pitch a story idea, place an ad, talk to the publisher — or even book a tanning booth — Cindy Thiel is your person at the Edgerton Earth, a tiny weekly newspaper in northwest Ohio.

Owner Cindy Thiel started out at the Earth in the 1980s, working as a bookkeeper for the former owners of the newspaper, which dates back to 1878. Though she didn’t have any previous interest in journalism, Thiel started typesetting, then doing advertising layout, and later photography and writing sports stories. In2006, Thiel bought the newspaper — and got an attached tanning salon as part of the deal.

“Now I do the whole thing, all by myself,” she said. “I am it, yes.

“I have a desk; you walk in and see the counter where you can pay for tanning or subscriptions. We took one room and put a wall down the middle. … It’s just crazy — small town, you know.”

Thiel used to have a few employees but lost them to things like caregiving duties or new opportunities. She never replaced them and, like many owners of the nation’s smallest newspapers in small towns, makes money by diversifying revenue streams and even becoming a one-person operation.

Let’s face it: Traditional newspapers today aren’t the most profitable businesses. But they provide a very important service by covering news the major outlets in nearby big cities won’t cover, and they must find business models that work, industry experts said.

People who live in areas served by small newspapers know they can go to the Internet, television, or the nearest big-city news outlet for national and international news. But if they want to know about a nearby festival, city council, school board, or church fish fry, they need the local newspaper — particularly one owned by local people who know and are invested in the community, said Andrew Conte, director of the Center for Media Innovation at Point Park University in Pittsburgh.

“By delivering those kinds of stories, that’s where local news outlets can create value,” Conte said.

On the business side of things, small newspapers provide local businesses a parallel opportunity to reach readers with advertisements they wouldn’t see in large national media, Conte said.

“(The newspapers) serve the public in a way that is meaningful to readers but also meaningful to commercial businesses who want to get their word out.”

Jim Iovino, Ogden Newspapers Visiting Assistant Professor of Media Innovation at West Virginia University in Morgantown, W.Va., directs a graduate program aimed at turning journalists into entrepreneurs who want to take over rural community newspapers around the country. The school’s NewStart Newspaper Ownership Initiative, which is in its first year, seeks to match the next generation of media entrepreneurs with small newspapers — mostly weeklies with a circulation of 1,000 to 5,000 — that are up for sale because their owners are reaching retirement age or just want to get out of the industry.

“We train folks on community journalism and the business side of things, and help them create new business models and structure,” Iovino said. “We match them up with people who are selling and help secure those deals. We help them learn how to make it sustainable for the long term.”

While there is no one-size-fits-all specific solution for each individual newspaper, which needs a personalized plan, the key foundation is combining many sources of revenue, Iovino said. The classic business model of print advertisers and paid print subscribers has crumbled.

“What we stress significantly is diversifying revenue streams so you’re not all that reliant on print subscriptions and print advertising,” he said.

Aside from selling paid digital subscriptions and ads along with the print versions, publications need to think outside the box for alternate sources of money, Iovino said. One possibility is creating sponsored content, where businesses pay the publication to write stories that they direct and approve. Newspapers also can create community events, and both sell tickets and bring in business sponsors. They can create a merchandising leg and sell things such as T-shirts.

Newspaper owners, Iovino said, must ask: “What are the needs that the community has, and what are the things the newspapers can do to fulfill those needs?”

“What they need at this point is basically an updated business model,” he said. “If you have that diverse revenue model, you can withstand a lot of these things better.”

Penny Abernathy, former Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics Professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has studied “news deserts” — places that have no local newspaper. Her research found that between 2005 and 2020, the United States lost a quarter of its newspapers: 2,100, about 2,000 of which are small dailies or weeklies.

Economically depressed communities are especially at risk of losing their newspapers, Abernathy said, and they suffer from not knowing what is happening with their school board, city hall, and neighbors when local reporters no longer have jobs.

“For me, when you lose a local paper, you lose the ability to know how you share the same problem and issues with people in your community,” Abernathy said. “My favorite definition of a good, strong news organization is that it shows you how you are related to people you may not know you’re related to.”

Although foundations sometimes support newspapers, they tend to fund organizations in big cities, so smaller newspapers are out of luck, said Abernathy, who recently accepted a role as a visiting professor at Northwestern University, in Illinois.

If small papers want to stay in business, they need three conditions to make money, Abernathy said. One, they must be located in a market with at least average economic or population growth. Two, the owner has to be creative and disciplined, and have the local autonomy and discretion to identify and meet the unique needs of both businesses and residents. Three, the owner has to have the capital to invest and experiment for five years.

Abernathy points to her home newspaper — The Pilot, a twice-weekly, 100-year-old publication in Southern Pines, Moore County, N.C. — as a strong example of a diverse business model. The Pilot has an editorial staff of 11, including reporters, editors, photographers, and designers. The paper has a circulation of about 12,000, with about 8,000 subscribers.

The Pilot has built a multimedia business that includes the newspaper; an independent bookstore called The Country Bookshop, which brings in prominent authors for signings; digital newsletters with targeted audiences, such as one for millennials; a digital ad agency; and lifestyle magazines for four North Carolina areas: Charlotte, Raleigh, Greensboro and Wilmington.

The company also publishes Pine Straw, a tiny local magazine that the Pilot publisher picked up 13 years ago in a swap for a set of golf clubs. David Woronoff — president and publisher of The Pilot, the name for the broader business as well as the paper — chuckles at the memory.

Diversity and personalized community service are the keys to business success for a newspaper, Woronoff said.

“We feel like if the only tool you have is a hammer, then every problem looks like a nail,” he said. In that case, the solution to everything is more of the newspaper, but that’s not the case, Woronoff said.

“Our core mission is to serve our community,” he said. “We put our community first, we put our advertisers second, and we put our shareholders third.

“That means we have to serve more than just people who want to pick up a printed copy of the newspaper,” said Woronoff, who thanks the paper’s loyal readership.

The Pilot, which opened in 1920, was going to celebrate its centennial in 2020, but will wait until the 101st anniversary due to the pandemic.

Nobody can expect to make big money running a small newspaper, said Thiel of the Edgerton Earth, which she bought when it was in a building that housed a hair salon with a back room for tanning. In 2011, she moved the newspaper to a downtown building with a separate area for her two tanning beds and one tanning booth. The newsroom consists of just her desk and computer in the divided room.

However, Thiel makes just enough to pay the bills and get by with her overall business — called SWW Publications Ltd. — and that is good enough for her. About 90 percent of Thiel’s income comes from the newspaper rather than the supplementary tanning, and when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, print circulation dropped from about 1,200 to about 450. She shut down printing for a while because advertising dried up and provided free digital subscriptions.

“Let’s put it this way: We paid the bills,” Thiel said about profitability. “Making ends meet … to me, that’s all I really care about. As long as I can pay the bills at the end of the day.”