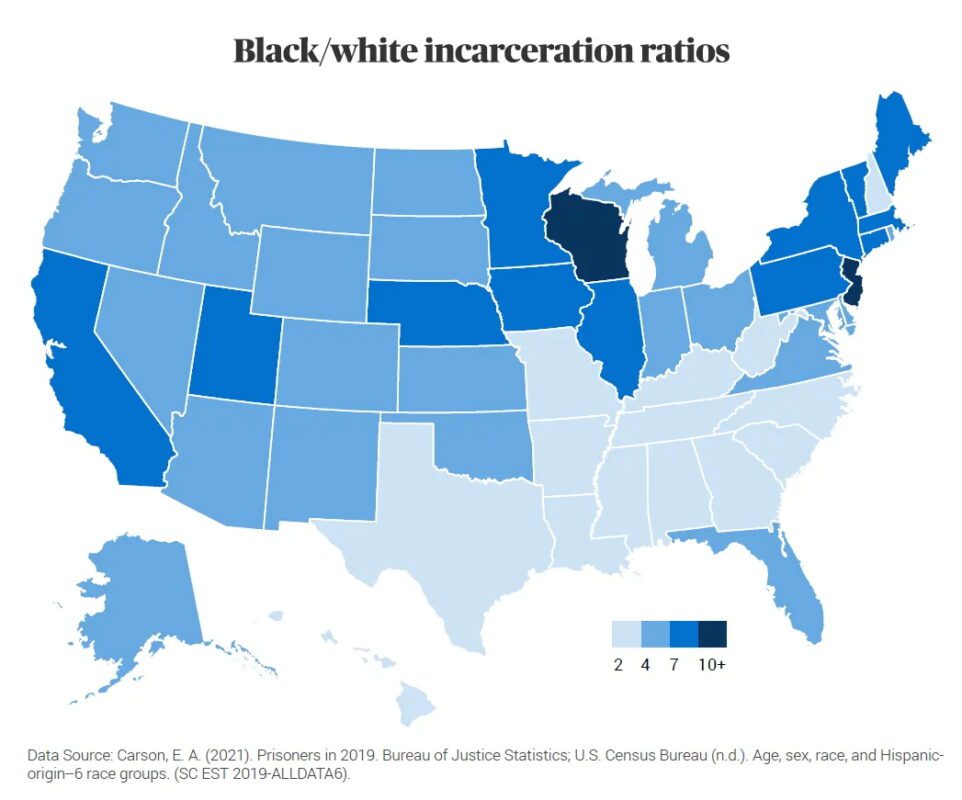

Wisconsin imprisons Black residents at a higher rate than any other state in the country, a new report found, highlighting long-standing and deep disparities in the state’s criminal justice system.

The report, authored by The Sentencing Project and released on Wednesday, used data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics to calculate states’ rates of imprisoning white residents and people of color.

A “staggering” one of every 36 Black Wisconsin adults is in prison, the report found. Black people comprise 42% of the Wisconsin prison population, but just 6% of the state’s population.

The analysis also examined the disparity in imprisonment rates between Black and white people. Nationwide, Black Americans are imprisoned at nearly five times the rate of white Americans, the report found, and in Wisconsin, the ratio is even higher: Nearly 12 times the rate.

The report cites pervasive racial bias across the criminal justice system. It notes that Black Americans face disproportionate arrest rates and factors that can lead to longer prison terms — including a greater likelihood of being charged as a habitual offender and more time spent in jail awaiting trial.

“To me, it’s like a slap in the face. How can we be the worst? That particular status quo is unacceptable.”

— Ramiah Whiteside, who was incarcerated for over 20 years

Re-entry is particularly difficult, according to Ramiah Whiteside, who was incarcerated for over 20 years. Now an organizer with EXPO, a Milwaukee-based advocacy organization for formerly incarcerated people, Whiteside encountered discrimination in finding employment, securing stable housing — and even buying life insurance.

“When it comes down to hiring you with a felony or waiting on other people less qualified, a lot of places wait,” he said.

For these reasons, incarceration is also associated with reduced lifetime earnings and negative life outcomes among children, contributing to high crime rates and “neighborhood deterioration” that exacerbate existing disparities, the report noted. Advocates have called for more funding for pre- and post-release services and efforts to counter the stigma attached to having a criminal record.

Milwaukee County Supervisor Ryan Clancy said governments “overinvest” in policing and punitive measures “rather than the systems and programs we know will make us safer and (give us) better places to live.”

Advocates for prison reform in Wisconsin were disheartened by the report’s findings, calling them “depressing” and “embarrassing.”

“To me, it’s like a slap in the face,” Whiteside said. “How can we be the worst? That particular status quo is unacceptable.”

While the report found some of the most extreme disparities in Wisconsin, the problem exists nationwide, even in states with relatively low rates of incarcerating Black people. Hawaii, the state with the lowest racial disparity, imprisons Blacks adults more than twice as often as whites.

The report also found that states in the northeast and upper Midwest showed the greatest racial disparities in their prison systems.

“If nothing else, this report says we’re all doing something wrong, including the advocates,” said David Liners, a statewide coordinator for Wisdom, a statewide faith-based social justice organization.

“We haven’t really raised the sense of urgency that as a state this is a complete violation of what we in Wisconsin like to think that we are,” Liners said. “We don’t like to think of ourselves as the most racist state in the union, or the harshest people on Earth when it comes to Black people … Unfortunately it’s not who we want to be but who we are right now.”

A 2020 study by the Wisconsin Court System found that men of color, particularly Black and Native American men, are significantly more likely to receive prison sentences than their white counterparts — 28% and 34% more likely, respectively, with white men 21% less likely than non-white men to receive a prison sentence.

Liners applauded The Sentencing Project’s recommendations for reducing the disparity. They include decriminalizing low-level drug offenses, eliminating mandatory minimum sentences and adopting racial impact statements to gauge the effect of proposed crime legislation on different populations.

“For Wisconsin, though, I believe we need something much more fundamental,” he said. “We need leadership to stop pretending that we have a slightly damaged system that needs a few adjustments. Instead, we need to re-imagine every step of the process, from policing to extended supervision, and everything in between.”

Others noted that Wisconsin’s split state government — a Republican-run Legislature and Democratic Gov. Tony Evers — makes sweeping changes difficult. “The challenge, of course, is amassing the political will in a divided government,” said state Rep. Evan Goyke, D-Milwaukee, and former public defender.

In a statement, Kevin Carr, secretary for the Wisconsin Department of Corrections, made a similar point.

“I understand that, for too long, with too little result and at too large a cost to taxpayers, Wisconsin’s criminal justice policies have increased incarceration and had disproportionate effects on communities of color,” Carr said. “Governor Evers offered multiple proposals related to criminal justice and juvenile justice reform in the budget he sent to the Legislature, only to have the Republican-controlled Joint Committee on Finance throw them out.”

Carr said the state prison system has taken administrative steps to lower the prison population by expanding eligibility for the Earned Release Program and changing community supervision policy, resulting in fewer people returning to prison. And although the prison population dropped during the pandemic — reaching its lowest level in two decades — it has begun inching back up past 20,000 as courts return to processing cases. The state’s total prison population as of Oct. 8 exceeded the design capacity of prisons by 16%.

Goyke pointed to some measures that could ease the impact of incarceration, including Assembly Bill 69, which passed the Assembly and is now before the Senate.

The bill would allow lower-level, nonviolent offenders, including those with convictions for drug possession, to get their records expunged. Currently, a person is only eligible for expungement if the judge makes that determination at a sentencing hearing, and only if the person is 25 or younger. The bill would eliminate those conditions.

“Thousands of people would benefit from this legislation,” he said, noting that more than 200 professions in Wisconsin bar some or all applicants with criminal records from getting licensed.

“I’m not suggesting it’s the only thing we should do as a Legislature,” Goyke added. “We need to take as many (steps) as we possibly can.”

Wisconsin has also seen calls for action from the judiciary. From the day she was sworn into office, Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Rebecca Dallet has stressed the imperative to reduce racial inequities in the state’s justice system.

Dallet was elected in 2018, one of three left-leaning justices on the seven-member court. After the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer in 2020, Dallet and dozens of current and retired state Supreme Court and appellate court judges called for a re-examination of how people of color are treated in Wisconsin’s justice system.

“We cannot turn a blind eye to the issues of racial disparity and mass incarceration,” they wrote in an open letter. “Too many people of color are behind bars in Wisconsin. We need to carefully consider treatment as a means of addressing issues of trauma, mental illness, and addiction.”

That letter led Dallet to form a group of representatives from the criminal justice system and community groups which she co-chairs with Bayfield County District Attorney Kimberly Lawton. A subcommittee of the state’s Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, the group is in the early stages of learning about the causes of inequity and possible solutions, she said.

“I think unfortunately Wisconsin has been at the top of the list of incarcerated people of color — specifically, African American — for years now,” Dallet, a former prosecutor, said in an interview. “It’s not an honor that we want to hold. It’s not an honor.”

Whiteside said he has seen small victories recently — such as the Department of Corrections’ decision to stop using terms such as “inmate” and “offender.”

“The fact that we’re having this conversation, and I’m included in this conversation — that’s a win,” Whiteside said. “Whether it’s the different language that the DOC used — saying ‘people in our care’ versus inmate or offender — those are small but big for us. … That’s a win. But all of that is not enough. Those statistics didn’t just happen overnight.”

Dee J. Hall contributed to this report. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Wisconsin Watch is a nonprofit newsroom that focuses on government integrity and quality of life issues. Sign up for the newsletter for more stories and updates straight to your inbox.