Wisconsin Watch is a nonprofit newsroom that focuses on government integrity and quality of life issues. Sign up for our newsletter for more stories straight to your inbox. and donate to support our fact-checked journalism.

About 50 abortion rights supporters stood on the bridge over the Wisconsin River into Sauk City on a sunny Saturday morning in mid-May.

They held signs reading “CHOICE” and “PROTECT ROE v. WADE” and cheered when passing cars honked in support.

Jennie Klecker brought three generations of her family out on the bridge for the demonstration: her mother and her daughter and niece, in the sixth and ninth grades.

“I’m here for them,” she says, gesturing to the girls. “They shouldn’t be forced to be mothers. These are human rights.”

A local group, Indivisible Sauk Prairie, organized the bridge demonstration. Across the state and country that Saturday, thousands gathered to protest in anticipation of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization that is expected to overturn the 49-year-old precedent guaranteeing a constitutional right to an abortion.

In Sauk City, a lone counter-protester wore a MAGA hat, yelled vulgarities and marched through the crowd. A woman stood across the street holding a large sign declaring: “70 PERCENT: ROE V WADE.”

Her sign reflected the sentiment from a recent Marquette University Law School poll, which found 69% of people nationwide oppose overturning the landmark decision. A Marquette poll from last year found 61% of Wisconsin residents support the right to an abortion “in all or most cases.”

While the Supreme Court’s final decision seems nearly certain to reverse federal protections for abortion rights, its impact on Wisconsin is far from clear. Observers agree that the state will see a legal battle over whether Wisconsin reverts back to a law from 1849 — a near-total ban on abortion passed 71 years before women had the right to vote.

That law makes it a Class H felony for anyone other than the mother to “intentionally (destroy) the life of an unborn child.” The maximum penalty is six years in prison and a $10,000 fine. The law provides an apparent exception for medically necessary abortions — referred to by an antiquated term “therapeutic abortion” — to “save the life of the mother.”

But what would constitute a legally allowable abortion? That is a daunting question for physicians across Wisconsin — not just those who specialize in providing abortion care — as they could soon face criminal prosecution for providing what they believe is a life-saving procedure.

“That uncertainty alone is going to likely severely limit, if not completely cut off, all abortion access in Wisconsin,” says Dr. Abigail Cutler, an obstetrician and gynecologist who practices in Wisconsin.

The Wisconsin Hospital Association did not respond to email and phone messages asking how overturning Roe would affect patients’ ability to get medically necessary abortions at hospitals.

In an interview, Attorney General Josh Kaul says the 173-year-old abortion ban may be unenforceable under a legal doctrine called desuetude, which holds that a long-unenforced law essentially becomes invalid. Kaul has vowed not to enforce that “draconian” law if Roe falls.

Wisconsin has multiple abortion laws passed after the 1973 Roe decision that acknowledged federal abortion rights, including several passed under former Republican Gov. Scott Walker. One could make an argument, Kaul says, that these statutes — which are currently enforced, as opposed to the 19th century ban — could imply that the right to an abortion remains intact in Wisconsin.

Kaul expects legal challenges seeking clarity on the status of abortion access in Wisconsin.

“We are in a process right now of evaluating what the different legal options are in the state,” Kaul says. “But who files those or what the exact arguments raised are, I can’t say.”

Wisconsin law ‘hostile’ to abortion rights

Wisconsin’s abortion laws are already considered restrictive.

Over the previous decade, under Walker, Wisconsin’s GOP majority in the Legislature passed a series of restrictions that turned the state’s landscape from “leans hostile” to “hostile” to abortion rights, according to the Guttmacher Institute, which researches sexual and reproductive health and rights.

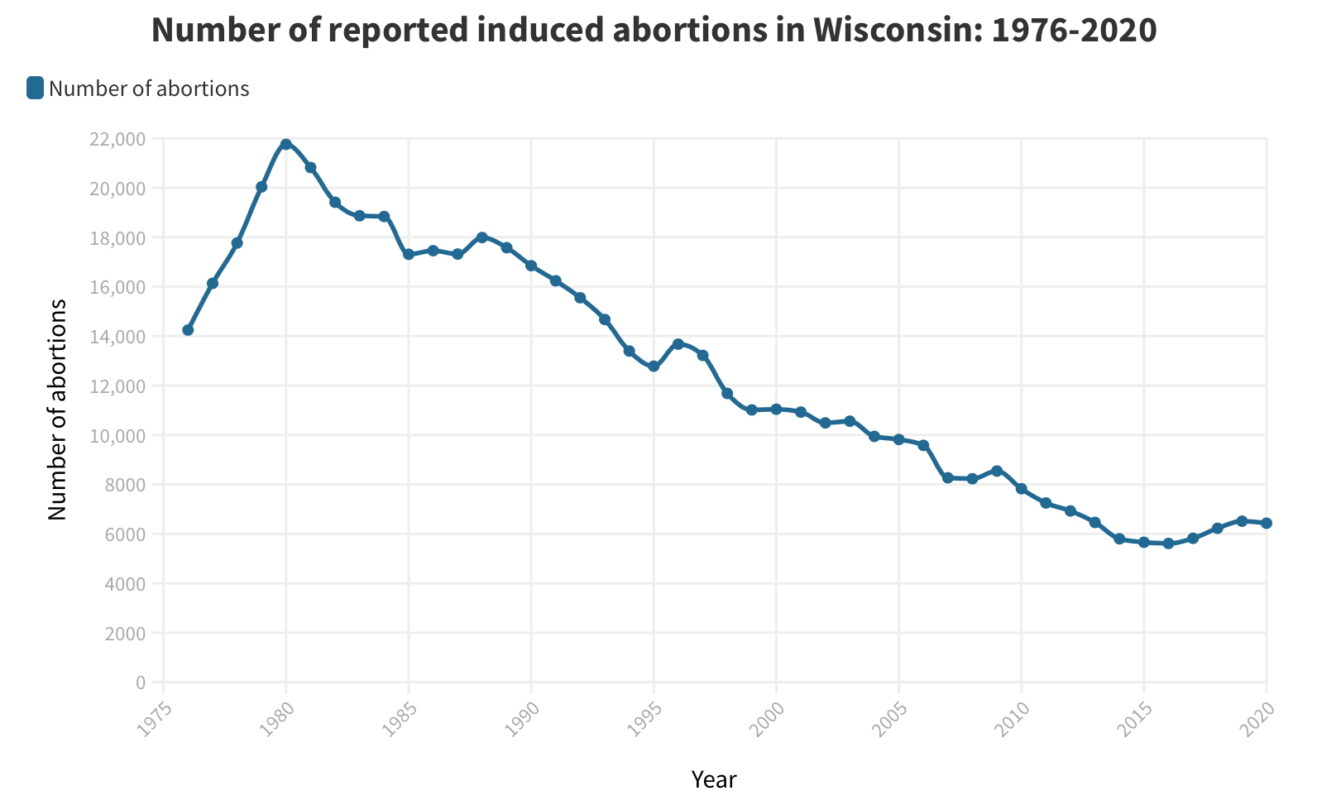

Over the past 45 years, the number of Wisconsin abortions has declined significantly. In 1976, the state Department of Health Services reported 14,243 induced abortions, rising to a high of 21,754 in 1980. By 2020, that number had dropped to 6,430.

University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Collaborative for Reproductive Equity (CORE) says Wisconsin already restricts many aspects of abortion, including banning government-funded insurance coverage, limiting availability through family planning programs, requiring mandatory counseling, ultrasounds and waiting periods for medication and surgical abortions and gestational limits, among other restrictions.

For example, Wisconsin law only allows licensed physicians to perform abortions, even though other medical professionals including nurse practitioners, certified nurse midwives and physician assistants can and do provide safe abortions in other states.

In Wisconsin, doctors must provide counseling and obtain spoken consent, both in person, at least 24 hours before administering care. In practice, a limited number of physicians can mean much longer waits between appointments — which can put patients beyond the 20-week gestational limit.

“None of these restrictions are evidence-based,” says CORE director Jenny Higgins.“There’s no medical reason for any of these restrictions. So just on that alone, these restrictions should be seen as onerous.”

Early law less restrictive

When originally passed in 1849, Wisconsin’s abortion ban was markedly less restrictive. According to the Legislative Reference Bureau, it classified the “willful killing of an unborn quick child” as first-degree manslaughter.

A “quick child” referred to a fetus that had noticeably moved in the womb. Prior to reliable testing, this was often the first indication of pregnancy. Quickening typically occurs “near the midpoint of gestation,” according to James Mohr, who wrote a 1978 book on the history of abortion in the United States.

Wisconsin’s original law, then, prohibited abortion only after an observable change that occurred about halfway through pregnancy, and sometimes as late as 25 weeks.

This statute became more restrictive in the following decade. By 1858, lawmakers had removed the reference to quickening, prohibiting abortion of an “unborn child” — language that remains in the statute today.

In addition to undergoing multiple revisions over the generations, Wisconsin’s pre-Roe abortion law has also faced legal challenges that complicate its interpretation and enforceability.

In 1970, just three years prior to Roe v. Wade, a panel of federal judges in the Eastern District of Wisconsin decided a case called Babbitz v. McCann. A physician sought an injunction against the Milwaukee County District Attorney E. Michael McCann, arguing that the abortion statute was unconstitutional.

The court agreed, holding that under the Ninth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, a woman has “the basic right … to decide whether she should carry or reject an embryo which has not yet quickened.”

According to UW associate law professor Miriam Seifter, the judges found a right to privacy based on precedents dating back to the late 19th century. The opinion concludes that the “mother’s interests are superior to that of an unquickened embryo,” regardless of whether that embryo is “mere protoplasm,” in the view of the physician, or “a human being,” in the view of the Wisconsin statute.

But the impact of that decision is complicated, Seifter says. As a federal district court decision, it’s “not formally binding.” Instead, it serves as “persuasive authority” — and may seem less persuasive depending on the Supreme Court’s eventual ruling in Dobbs. In other words, although the judges in 1970 found a federal constitutional right to abortion in Wisconsin, courts today are not required to follow that ruling.

There’s a “tangled series of abortion-related laws in Wisconsin,” Seifter added. “Most likely some court will need to figure out whether those statutes are enforceable or compatible (and) how to read them together.”

And any challenge filed in state court would likely end up before the Wisconsin Supreme Court, currently controlled by a 4-3 conservative majority. Justice Brian Hagedorn, sometimes deemed a swing voter, was endorsed by two Wisconsin anti-abortion groups.

Little access to abortion in Wisconsin

Today, Wisconsin has only four clinics providing elective abortion procedures: two in Milwaukee, one in Madison and one in Sheboygan. Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin operates three of the four clinics, and Affiliated Medical Services operates one of the Milwaukee locations.

Sheboygan’s Planned Parenthood clinic only provides medication abortion, which is induced through pills, and Wisconsin has some of the strictest medication abortion laws in the country.

The UW-Madison’s CORE notes that nearly 70% of Wisconsin women between the ages of 15 and 44 live in a county that lacks an abortion care clinic. That statistic does not account for transgender men and non-binary people who also could become pregnant.

Higgins says cost is a key barrier to accessing abortions. Federal law prohibits federal Medicaid funding for abortions. Wisconsin law prohibits state, local or federal funding for programs that “provide, promote, or encourage abortion services or make abortion referrals,” according to CORE.

Wisconsin’s Medicaid and BadgerCare health insurance programs do not cover elective abortions except when deemed medically necessary or following sexual assault or incest that has been reported to law enforcement.

Research shows people often seek abortions because they cannot afford to raise a child, but the cost of abortion often remains out of reach, Research also shows that women who are denied wanted abortions suffer physically, psychologically and financially for years afterwards — conditions their children suffer too.

Post-Roe agenda unclear

Meanwhile, Wisconsin’s Republican legislative leadership remains mum on any post-Roe plans.

Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, R-Rochester, and Senate Majority Leader Devin LeMahieu, R-Oostburg — as well as ardent abortion opponent Sen. André Jacque, R-De Pere — did not respond to Wisconsin Watch’s emailed questions about their plans. Vos’ staff shared a prepared statement that read, in part, “I’ve always been proudly pro-life. If this is the final ruling, it will empower states to make their own decisions.”

Wisconsin Democrats have tried and failed to shore up abortion rights, and at this point, any attempts to pass new legislation would be largely symbolic.

“Our ability to actually present and pass legislation that would attain what we hope, which is unimpeded access to reproductive health care, will probably not be successful,” says Senate Minority Leader Janet Bewley, D-Mason, who is not running for re-election.

Two prominent anti-abortion groups in Wisconsin celebrated the possible end to Roe, but they have separate visions for the future.

Wisconsin Right to Life, a non-religious organization, supports exceptions that allow for medically necessary abortions, legislative director Gracie Skogman says. However, the group opposes an exception for rape or incest — which also is not in the 1849 law.

“Our position has always been to support women who are in their utmost need, and when we think about the heartbreaking situation of rape, that is the utmost violence against women,” she says. “But an abortion only continues that cycle of violence.”

Matt Sande, legislative director for Pro-Life Wisconsin, argues that removing a medical exception will not prevent people from obtaining life-saving treatment for ectopic pregnancies — which involves removing a non-viable embryo from the fallopian tubes — because “legally such operations are not considered abortions.”

The leaked U.S. Supreme Court draft in Dobbs, and current and proposed legislation in states like Texas and Louisiana, also raised alarms that lawmakers might eventually criminalize people who have abortions — or even use contraception. In Texas, a district attorney charged a woman with murder for a “self-induced abortion” — even though murder legally does not apply if a woman terminates her own pregnancy. Eventually, he dropped the charges.

Both Pro-Life Wisconsin and Wisconsin Right to Life say they’re not seeking to criminalize people for having abortions. Wisconsin law did criminalize women who sought an abortion starting in 1858 — later rendered unenforceable by court decisions— but such a penalty remained on the books until 2012.

Pro-Life Wisconsin also opposes contraception, claiming on its website that birth control leads to the “attitudes and even moral character that are likely to lead to abortion.” But Sande says the group has no plans to push for a legislative ban on contraception.

Who would enforce the law?

In the interim, while court battlelines form, access to abortions will certainly diminish.

Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin will pause providing abortions “until there’s clarification from the court of competent jurisdiction, declaring that (1849) law is not enforceable,” says Mike Murray, vice president of governmental relations for Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin, the largest provider of elective abortion care.

Were physicians to continue providing abortions in any of the four clinics — or in any other setting — enforcement of laws prohibiting abortion would lie with prosecutors.

“When it comes to holding people accountable, it would be a question of, are investigative agencies going to investigate?” Kaul says.

So long as the Democrat remains attorney general, the Wisconsin Department of Justice will not investigate abortions, he says. But Kaul is facing re-election in November. Two of his Republican challengers, Fond du Lac County District Attorney Eric Toney and former lawmaker Adam Jarchow, have both tweeted support for a decision overturning Roe. Toney also criticized Kaul’s refusal to enforce the old law. He declined to provide additional comment on the record, and Jarchow did not respond to emails requesting comment.

Local prosecutors in Dane, Milwaukee and Sheboygan counties — which currently have abortion clinics — could choose to pursue charges against providers if abortions continued.

None of these district attorneys — Democrats Ismael Ozanne and John Chisholm and Republican Joel Urmanski — returned multiple emails and phone calls asking if they would prosecute physicians providing abortions if Roe is overturned. However, in 2020, Chisholm signed an open letter announcing he would not prosecute anti-abortion laws.

All three district attorneys’ terms end in 2025. The Wisconsin statute of limitations for most felony charges is six years, meaning their potential successors could pursue charges targeting physicians who provided abortions after Roe was struck down — even if the current district attorneys declined to do so.

The future of abortion rights in Wisconsin, then, likely lies at the ballot box, in statewide and local elections for governor, attorney general, Supreme Court, state Legislature and district attorney.

“It’s scary,” says Jennie Klecker, out on the Sauk City bridge. Klecker’s life was saved by removing an ectopic pregnancy that occurred between the births of two of her children.

“I’m here for their future. I’m here for my future and (the future of) women in general.”

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Phoebe Petrovic joined the Center in 2019 as a Report for America corps member. She is leading creation of an investigative podcast examining prosecutorial power. She formerly worked at WPR through the Lee Ester News Fellowship and was an editorial intern at “Reveal” from the Center for Investigative Reporting. She also worked as a producer for NPR’s “Here & Now” and a reporter for WCPN ideastream. Petrovic earned a bachelor’s degree in American Studies from Yale University, where she founded and led various audio projects.