Before that fateful day in spring 2020, Michigan Sen. Erika Geiss felt safe in Lansing.

“Even on [annual] open carry day,” Geiss (D-Taylor) said. “I didn’t feel there was an active existential threat to my existence.”

As a Black lawmaker from a Southeast Michigan district populated by plenty of hunters, the only real pang of concern Geiss felt during those armed gatherings at the state Capitol was about whether someone may not carry their firearm properly and accidentally cause an injury.

But those were the “before times,” she says. Everything changed on April 30, 2020, more than five years after she was first elected to the Legislature.

“I will never forget that date,” Geiss said. “That was a day that palpably changed this place and the sense of safety here.

“Lansing, the Capitol, is a very different place since that day.”

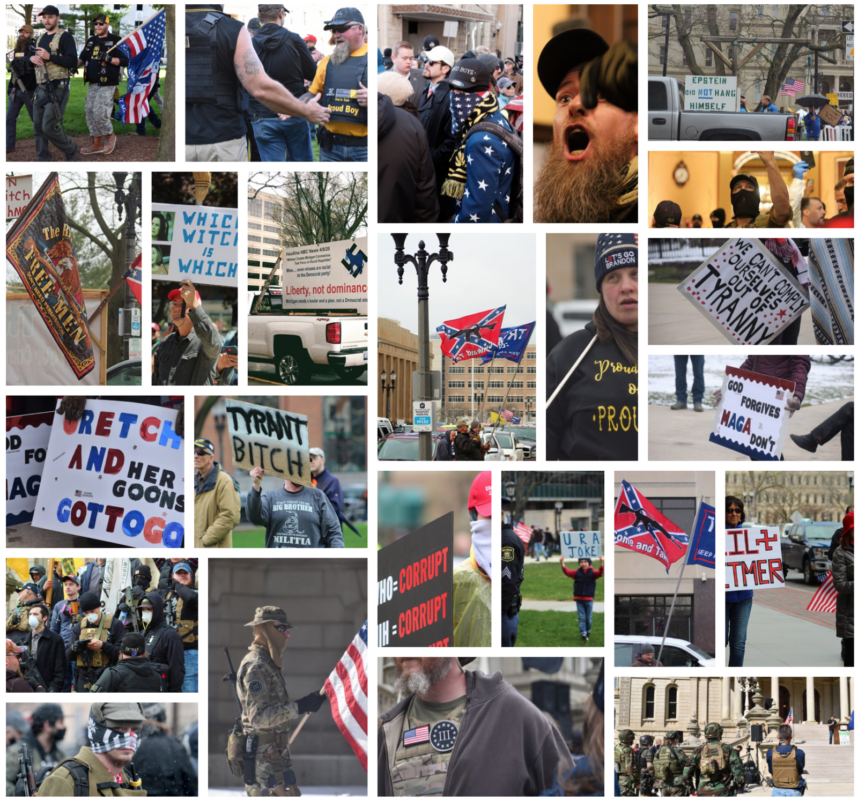

On that day, about 600 armed right-wing protesters rallied against COVID-19 health measures on the front Capitol lawn and pushed their way into the building. About 20 of them, some brandishing long guns and wearing tactical gear, entered the Senate gallery and loomed over lawmakers during session.

Some legislators, like state Sen. Dayna Polehanki (D-Livonia), said they feared for their life. Some wore bulletproof vests.

For Geiss, that was when she felt a palpable shift. What she experienced that day has never quite left the Capitol, she said, as members still continue to engage in the types of dangerous rhetoric and behavior that was brought to Lansing on that spring afternoon two years ago.

“Disturbing doesn’t even begin to describe it,” Geiss said.

“It seems like this coalescing of white nationalism, of Christian nationalism, has really morphed into something that we haven’t seen since the Civil Rights era. And something that seems to have been steeping and brewing very slowly and underneath the surface for quite some time.”

Indeed, the resurgence of white nationalism — which calls for a white nation and has deep roots in racism, antisemitism, anti-feminism and conspiratorial anti-government ideas — has, in many ways, shifted America’s political and social landscape toward the far-right. Rather than being condemned as they might have in years before, politicians who espouse these ideas are now often rewarded with name recognition, public attention and media coverage that can be accompanied by a bump in fundraising and perhaps even a high-profile endorsement.

And the fallout from the muted acceptance of such extremist views leaves in the crosshairs people of color, government employees and other vulnerable communities.

“They are going for the targets that are the most vulnerable, and we know that the targets that are most vulnerable are women, people of color — specifically Black women get it probably worse than anyone,” said Melissa Ryan, who runs the Ctrl Alt-Right Delete newsletter that details the rise of far-right extremism.

That phenomenon of white nationalist ideologies being publicly embraced by political leaders, candidates and other right-wing officials is unique to the last few years, according to an analysis by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC).

Experts say such rhetoric accelerated after being brought into the limelight by former President Donald Trump. Like elsewhere around the country, white nationalist politics continue to leave a mark on state and local politics from county boards to the Michigan Legislature.

“We’ve seen a mainstreaming of ideas that were really, really fringe, in a way that I really never thought was going to be the case,” said Heidi Beirich, chief strategy officer at the Global Project against Hate and Extremism.

Sympathetic officeholders and candidates

Beirich began tracking far-right extremism in 1999 while working at the SPLC. She remembers when candidates and officials who embraced extremist ideas were “kicked to the curb” by Republicans who did not want to align themselves with the far-right.

But, “by the time Trump won the primaries [in 2016] and was on his way, that dynamic was over,” Beirich said. “People who made racist statements, misogynistic statements, who advocate policies that used to be on the fringes, were now embraced.”

Still, she emphasizes that Trump was only the accelerant to a movement that was already growing. Right-wing extremism was there, under the radar for most. Trump’s candidacy brought the movement mainstream.

“We’ve seen a mainstreaming of ideas that were really, really fringe, in a way that I really never thought was going to be the case.” – Heidi Beirich, chief strategy officer at the Global Project against Hate and Extremism.

Those ideas have seemingly saturated the politics of Michigan’s top Republicans, including Senate Majority Leader Mike Shirkey (R-Clarklake) and Michigan Republican Party Co-Chair Meshawn Maddock.

Shirkey, who has been called out during Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s tenure for making racist, misogynistic, conspiratorial and generally insensitive remarks, met with some of the armed protesters in the Senate gallery on April 30, 2020 and blocked reporters from covering their conversation.

Months later, Shirkey arranged a meeting in his office with leaders of three militia groups involved. He said they “talked about their messaging, their purpose, what they are trying to accomplish and how they could improve their message.” He claimed they get “a bad rap” and defended them for being patriotic citizens who are misunderstood.

On Oct. 8, 2020, Shirkey and then-House Speaker Lee Chatfield (R-Levering) attended an anti-COVID lockdown protest on the Capitol lawn — the same day authorities announced charges against 13 men who allegedly plotted to kidnap Whitmer, put her on trial and execute her. The conspirators, two of whom were acquitted on Friday, had attended Lansing lockdown protests.

Federal authorities said some of the men had ties to white nationalist groups like the Boogaloo Bois.

Shirkey has also baselessly claimed that the Jan. 6, 2021 insurrection was not carried out by Trump supporters, but by antifa and enemies of Trump. The meritless claim is commonly espoused in QAnon circles.

Lt. Gov. Garlin Gilchrist said Shirkey’s attitude and actions toward militias and related groups are “incredibly problematic,” and “legitimize[s] those people who came in to commit violence.”

Shirkey did not respond to a request for comment.

Just four days after the April 30, 2020 incident in Lansing that left lawmakers of color particularly anxious about their safety while at work, during a rare Friday session, state Sen. Dale Zorn (R-Ida) sported a face mask that appeared to have a Confederate flag design on it.

Gilchrist, Michigan’s first Black lieutenant governor, was presiding over the chamber at the time.

Facing backlash, Zorn denied it was a Confederate flag, but said he told his wife “it probably will raise some eyebrows.” The Republican then defended the Confederate flag as a part of American history.

“Even if it was a Confederate flag, you know, we should be talking about teaching our national history in schools and that’s part of our national history and it’s something we can’t just throw away because it is part of our history,” Zorn said.

Zorn eventually apologized, but Black lawmakers who pushed for Zorn to be censured and for Confederate flag imagery to be banned from the state Capitol never saw their requests answered.

More recently, Maddock — who’s married to state Rep. Matt Maddock (R-Milford) — received widespread condemnation when she referred to Gilchrist as a “scary masked man” after he uploaded a video speaking about COVID-19 measures to Twitter.

“Show this video to a [sic] babies and watch them cry,” Maddock said, quote-tweeting the video. “Scary masked man should #StayHome.”

Whitmer and others condemned the remark as racist.

Maddock did not respond to a request for comment.

A number of candidates for office in Michigan also espouse similarly white nationalism-tinged ideas, from AG candidates running on platforms of debunked election conspiracies to a state House candidate being publicly antisemetic, anti-feminist and pro-white majority.

“Feminism is only applied against white men, because … It is a Jewish program to degrade and subjugate white men,” reads a Facebook graphic reposted by state House GOP nominee Robert Regan.

Regan has posted other antisemitic conspiracies on Facebook, as well as a slew of baseless conspiracy theories about COVID-19.

Regan gained widespread public backlash last month, when he said during a virtual panel that rape victims should “lie back and enjoy it.”

The Michigan Republican Party criticized his comments, but did not disavow Regan or ask him to withdraw from the race that he is heavily favored to win.

“Mr. Regan’s history of foolish, egregious and offensive comments, including his most recent one are simply beyond the pale,” party co-chair Ron Weiser said in a statement. “We are better than this as a party and I absolutely expect better than this of our candidates.”

Ryan said white nationalist views like Regan’s and others have become so prevalent in GOP candidates that it has become “easier to track who isn’t” subscribed to those ideas than who is.

“It was amazing to me just how rapidly the Overton window moved on what language was acceptable in political rhetoric and online,” Ryan said.

Some candidates have used their controversies to fundraise or gain more publicity for their campaigns, like GOP gubernatorial candidate Garrett Soldano. After receiving backlash and national coverage for saying that rape victims who become pregnant must “protect that DNA and allow it to happen,” no matter the circumstances, Soldano said the attention was “great news” for exposing his candidacy to a national audience.

Other Republicans with similar viewpoints include Kristina Karamo, a candidate for Michigan Secretary of State who has spoken at a QAnon conference, and attorney general candidate Matt DePerno, who has promoted the long-debunked conspiracy that Trump would have won the 2020 election if not for widespread voter fraud.

Both have been endorsed by Trump.

Citizen activity and online hate

Emboldened by Trumpism and promoted in conservative circles, the ideas and conspiracies held by white nationalists have led a large chunk of the Republican base itself to buy into the rhetoric.

According to a December poll conducted by the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, only 21% of Republicans nationwide say President Joe Biden’s 2020 victory was legitimate.

“There seems to be a greater comfort level of people who have just really blatantly racist, white nationalist views to just parade that out publicly. It is scary.” – Michigan Sen. Stephanie Chang, D-Detroit

The networks of conspiracies and hate have only exploded more through the popularization of social media. Facebook groups with hundreds to thousands of members share a broad range of conspiracies and violent messages, including some in 2020 thathoused violently misogynistic remarks and threats toward female officials including Whitmer, Attorney General Dana Nessel, Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson and others.

“There seems to be a greater comfort level of people who have just really blatantly racist, white nationalist views to just parade that out publicly,” said state Sen. Stephanie Chang (D-Detroit). “… It is scary.”

“In the U.S., [with] people who are anti-COVID response, you also saw swastikas and Confederate flags and these types of things,” Chang said. “It’s concerning because you’re seeing people mixing some of these views up and giving another platform for some of these really extreme nationalist views.”

That all came to a head in October 2020, when state and federal law enforcement unveiled a foiled militia plot to violently overthrow the Michigan government, kidnap and execute Whitmer, subdue law enforcement, burn down the Capitol building, kidnap other government officials and instigate a new civil war.

Two of the men who allegedly participated in that scheme were acquitted of charges Friday, while a jury could not reach a verdict on the other two.

Many who ran in those circles also participated in the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. During Trump’s second impeachment trial, Nessel and others have said the April 30, 2020, storming of the Michigan Capitol was a “dress rehearsal” for the insurrection less than a year later.

“With the rise of social media and the internet, you don’t have to be some card carrying member of a group to ascribe to extremist ideas about race. You can just be involved in online networks,” Beirich said.

Ingrained in history, fueled by far-right funding

Extremist right-wing groups are often thought of as a problem primarily for Southern states, with a prominent example being the 2017 alt-right protest in Charlottesville, Va., in which participants chanted, “Jews will not replace us” and other racist and xenophobic rhetoric.

But the Midwest, particularly Michigan, has also been a breeding ground over the years for grassroots extremism. An estimated 100,000 Michiganders were Klansmen during the 1920s. Ku Klux Klan (KKK) hotspots formed in the state, including near Howell, where infamous Michigan KKK Grand Dragon Robert Miles held hate rallies and cross burnings until his death in 1992.

The KKK’s presence in Michigan is no longer what it used to be, and the SPLC has not recorded an instance of the group in the state since 2019 in Alpena. But as the KKK’s influence died down, the anti-government influence of militias found new life.

The most well known group, the Michigan Militia, took root in the state just two years after Miles’ death. It has been tied to the deadly 1995 Oklahoma City bombing and is known for having a range of conspiratorial ideas about government and other issues.

Experts say this militia- and KKK-rich history may have made Michigan uniquely positioned to support white nationalism ideals and let them fester once the opportunity arose.

“[Michigan] has an infrastructure with militias already, and then there’s a lot of money between the DeVos family and others. [So] I feel like Michigan just gets pummeled especially with it,” Ryan said.

The Grand Rapids-based billionaire family of Betsy DeVos, former U.S. education secretary under Trump, has long provided funding for conservative causes in Michigan. After right-wing rhetoric began to turn against Whitmer’s COVID-19 orders in early 2020, the DeVos family donated to groups that organized in opposition to the health measures, including the Michigan Freedom Fund.

With solid support and funding, including from the Michigan Republican Party, those groups continue to organize protests against COVID-19 restrictions (which no longer exist in Michigan) and the outcome of the 2020 presidential election.

According to the SPLC, there are at least 18 known hate groups in Michigan as of last year. Beirich said numbers like this in recent years are about double of that recorded in the early 2000s.

Feeling the impact

Many lawmakers of color have been vocal about the personal toll the last few years have taken, particularly since the 2020 election brought about a groundswell of often violent anti-government rhetoric. Many Black lawmakers have experienced an uptick in credible death threats against them and their families.

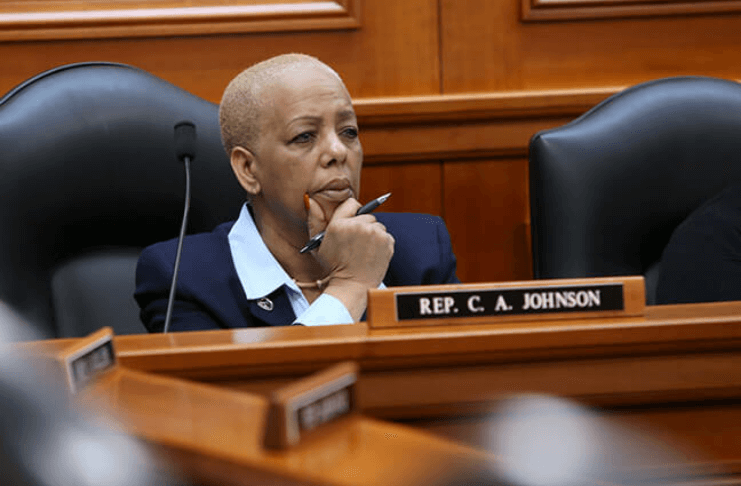

That includes state Rep. Cynthia Johnson (D-Detroit), who says she has received thousands of voicemails containing racist threats against her life. The calls started coming in after former Trump lawyer Rudy Guiliani made a highly publicized appearance before the state House Oversight Committee in December 2020 and promoted election conspiracies.

Johnson was the Democratic vice chair on the panel.

“These guys keep doing it and it keeps becoming more intense, because there’s really nothing in place to stop them,” said Ryan, the far-right extremism expert.

Since spring 2020, lawmakers of color have pleaded with GOP leadership in Michigan to enact rules to make them feel safer in the state Capitol, including a ban on firearms.

Those requests to legislators have mostly fallen on deaf ears, although Shirkey did eventually reverse course and support the open-carry ban that the Michigan State Capitol Commission (MSCC) passed nearly a year after the infamous 2020 incident. House Speaker Jason Wentworth (R-Clare), however, opposed the ban.

Geiss described it as “difficult,” “frustrating” and “sad” to work alongside members who are complacent in regards to the concerns that she and her colleagues feel.

“We are still being ignored and challenged by people who have some semblance of power and authority,” she said.

Aside from individual safety concerns, also problematic are GOP bills in recent months that have aggressively pushed back against the idea of teaching students about America’s racially oppressive history.

“They are going for the targets that are the most vulnerable, and we know that the targets that are most vulnerable are women, people of color — specifically Black women get it probably worse than anyone.” – Melissa Ryan, who runs the Ctrl Alt-Right Delete newsletter that details the rise of far-right extremism

From book bans to legislation prohibiting critical race theory (CRT) from being taught in schools, some say this is yet another facet of white nationalism ideals trickling into real-life policy changes.

“I think it is a very subversive way to inhibit or marginalize people in this country,” said state Rep. Joe Tate (D-Detroit). “Clearly when you want to undermine democracy, these were methods that were used in the past. So it’s unsettling.”

CRT is a college-level theory that examines the systemic effects of white supremacy in America and is not taught in the overwhelming majority of Michigan K-12 schools.

“It’s sad, because you think you come to this space of such remarkable esteem, to be able to be shaping policy and hopefully making things better for everyone, especially folks who have been traditionally marginalized,” Geiss said.

“And yet, you have people who have come here to do harm. It’s sad, it really is sad.”