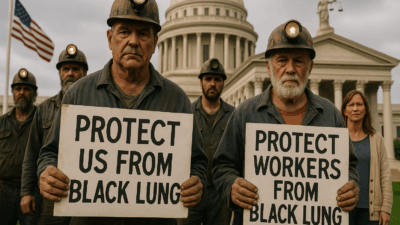

As the federal government moves forward with a “reorganization” that has left the Coal Workers Health Surveillance Program (CWHSP) largely unstaffed, attorneys for West Virginia coal miners are asking a federal judge to issue a preliminary injunction to keep the program running and grant miners a protection against developing dangerous black lung disease.

During a recent hearing, attorneys for the coal miners argued that the shutdown of the CWHSP — which operates within the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) — means the government is not meeting its legal obligation to coal miners or others as the work the agency is statutorily required to do is no longer being performed.

Attorneys for the federal government argued that the closure of the CWHSP — as well as other departments within NIOSH — is temporary.

Workers were notified that they were to be on administrative leave on April 1. Last week, some were told to return to work. But this week they were once again moved back to leave and permanent terminations are slated to take place come June.

NIOSH as well as the services performed in it, attorneys for the government said, will eventually return in a reorganized form under the federal Department of Health and Human Services. As such, they contended that the lawsuit on behalf of coal miners was premature.

Those testifying during the hearing in front of U.S. District Judge Irene Berger included coal miners, epidemiologists from the CWHSP and supervisors from within NIOSH.

No one, including the attorneys representing the federal government, provided details or a timeline for when the agency would resume the duties it is required by law to perform.

Laura Reynolds, a supervisor over the CWHSP, was asked if she was aware of any plans or discussions happening to transfer the agency’s services to U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Her response was one word: “No.”

Scott Laney, who worked as an epidemiologist at NIOSH, said the community of researchers and providers qualified to do the work done by those at the CWHSP is quite small. He hasn’t heard of anyone being asked to do it and has not been included in any plans to train others.

“There is nobody who does the surveillance and breadth of what we do at NIOSH [for black lung],” Laney said.

Without plan to resume services, coal miners left exposed to dangerous dust

Meanwhile, coal miners who have been diagnosed with black lung — including Harry Wiley, a coal miner in Raleigh County who is the lead plaintiff on the class action suit — are in a dangerous position.

NIOSH plays a critical role in the Part 90 program, which allows workers diagnosed with black lung to transfer to a less dusty part of a mine without facing retribution or negative repercussions from a mine operator. Miners transferred under the rule have their pay, benefits and hours protected while being able to work in an area that is less likely to advance their black lung disease.

In order to qualify for Part 90, miners anywhere must have their black lung testing results evaluated and marked eligible by a NIOSH worker in order to be approved.

But now there are no NIOSH workers. Laney said labs certified to test miners for black lung were instructed to stop in April since there was no one at the CWHSP to evaluate the results.

This leaves Wiley, who was diagnosed with black lung in November and who applied for a transfer under Part 90, without any options to protect himself from the dangerous disease advancing.

And the disease will advance, said Noemi Hall, another NIOSH epidemiologist.

The best protection to stop the progression of black lung — which has no cure and few treatment options — is prevention and reducing any exposure to coal mine dust, Laney said.

“We know that this intervention [of transferring workers to less dusty areas] works from the science,” Laney said. “[It’s] very clear in the scientific research.”

Debbie Johnson, the black lung program director at Bluestone Health in Princeton, told the court she knows of at least four coal miners from her clinic who are depending on the CWHSP to resume services.

Two have already entered their applications for a Part 90 transfer and two others need their results evaluated and certified.

None have heard from NIOSH.

Anita Wolfe, who retired from NIOSH in 2020 but still worked for the agency on a contract basis, said the CWHSP could see more than 5,000 x-rays a year that need to be evaluated. That’s 5,000 workers who could be at risk of developing a complicated and severe form of black lung disease without intervention.

Freeze on CWHSP occurs while silica dust rule under threat

While the federal government says its sorting out what a “reorganization” of NIOSH and the CWHSP will look like, it has also delayed the implementation of a federal labor rule that would have limited miners’ exposure to dangerous silica dust for the first time ever.

That rule was meant to go into effect in April.

It’s been delayed until August, however, partially due to the shakeups at NIOSH and the critical role workers there would have played in its implementation.

Sam Petsonk, a labor attorney representing the miners in their lawsuit against the federal government, said in an interview after the hearing that without the silica rule and without Part 90 transfers, miners are left with little to nothing to protect themselves.

“West Virginia coal miners fought to create these programs because workers here walked off the job, picketed and demanded protections for themselves and miners throughout the world,” Petsonk said. “This whole program was created to protect our miners. And now the government isn’t doing its part.”

Meanwhile, more than just the response actions NIOSH is mandated to perform are going undone. The agency was also responsible for critical research to aid in identifying and preventing black lung in miners.

That’s especially important today in central Appalachia, where the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that about 20% of the region’s coal miners are suffering from black lung — the highest rate detected in more than 25 years. One in 20 of the region’s coal miners are living with the most severe form of the condition.

And the resurgence of black lung is hitting coal miners at younger ages than ever before. This is due to miners, because of a lack of easily accessible coal, being forced to dig through more silica-rich sandstone than their predecessors in order to reach what little coal remains.

“We’re seeing a lot of younger miners who are at that point [of needing a Part 90 transfer],” Johnson told the court.

Before being told not to come to work in April, Hall was researching cases of black lung where individuals did not show symptoms but were developing the disease. Hall hoped that research could go toward working with miners to get tested early and frequently throughout their careers in order to stop symptoms from onsetting.

Now, she said, that work has been dropped and she doesn’t expect it to pick back up again.

While on the stand, both Hall and Laney were asked two questions by Mike Becher, an attorney from Appalachian Mountain Advocates who is representing the coal miners.

“Do you feel through your work you’ve made a difference in the lives of coal miners?” Becher asked.

“I know that to be the case because of the scientific evidence,” Laney responded.

“Yes,” said Hall.

“Do you feel you’ve saved miners’ lives?” Becher asked.

“I do,” Laney said.

“Yes,” responded Hall.

The class action lawsuit against the federal government was filed on behalf of miners by Appalachian Mountain Advocates, Mountain State Justice and Petsonk PLLC in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of West Virginia on April 21, 2025.

Judge Berger said she would have a response to the plaintiff’s request for a preliminary injunction to order NIOSH to resume its work “soon.”