As the destructive war in Ukraine drags on, some in the United States and Europe have grown weary of the fight, while leading Republicans like Trump and JD Vance spread lies aimed at undermining the Ukrainian struggle.

Postindustrial is proud to partner with The Ukrainians Media, a group of Ukrainian journalists dedicated to documenting the war by telling personal, sometimes gut-wrenching stories from the front. We applaud their courage and dedication to telling stories that illustrate bravery, heartache, and loss caused by the Russian invasion of a sovereign nation.

The late great American author Kurt Vonnegut wrote this about creating a captivating story: “Make awful things happen to your leading characters in order for the reader to see what they’re made of.”

I can confidently say that Ukrainians have endured enough over the last several years to reveal their true character to the world.

Some say tough times reveal our true selves; others believe we grow most when facing adversity. I learned that during the war in Ukraine, we discovered something completely new about ourselves and the world. This is knowledge that we never sought, and its cost is impossible to measure.

Covering an ongoing, destructive, and deadly conflict isn’t what we want to do

We should have been proud that our book, “77 Days of February,” a collection of stories and reportage from the early stages of the war, was translated into English, as translations like this don’t happen often.

But in truth, we wish it had been a different book with entirely different stories to tell.

We should have been able to admire our rescuers and firefighters during peaceful times when they release charity calendars filled with their portraits. Instead, we worry about them pulling people from the rubble every day—victims of Russian missile strikes—as they continue their life-saving work under unbearable circumstances, documenting their day-to-day life in heartwrenching photography projects.

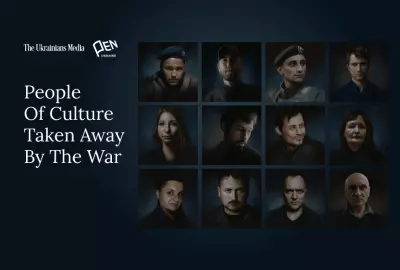

We would have preferred our writers to pen new books, host poetry evenings, visit children in schools to read them fairy tales—not for them, like Victoria Amelina, to be killed by a Russian missile strike, leaving us to write about them in projects titled “People of Culture Taken Away by the War.”

“I wish I’d never made this film,” said Mstyslav Chernov while receiving the first Oscar in Ukrainian history. We all share that wish—that this film had never been made, that Russia had never attacked our country, that Mariupol and hundreds of other cities had never been destroyed.

I wish I had never known just how resilient Ukrainian children are. I wish I had never edited the English translation of the story about little Romchyk Oleksiv, who survived a Russian missile strike in Vinnytsia but suffered multiple injuries and burns. Yet we published an entire anthology titled “Unbroken,” containing stories about people who survived the horrors of war and found the strength to keep moving forward.

I wish…

I wish none of this had ever happened.

But it is happening, and it is our reality. We don’t have the luxury of standing on the sidelines. We don’t have the privilege our colleagues from other countries have: to tell Ukraine’s story and then go home. We must do it all, here, at once.

****

My colleague, Danylo Pavlov, our media photographer and chief photo editor, often says that capturing the war through a camera lens makes him feel helpless—witnessing suffering while only being able to take a photo. After the explosion at the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant, he went to Kherson and took hundreds of photos, including one of a dog being rescued from the floodwaters.

Locals, seeing him take pictures, gave him judgmental looks. One told him to sell his camera and buy a boat, saying it would be more useful.

This moment illustrates the questions we, as Ukrainian journalists, now face. In peaceful times, it was easy to separate the personal from the professional. But now, we can’t just observe. Are we helping others or merely documenting? This is the question we live with daily—and,whether we want it or not, we become the heroes of our own stories, living in two worlds at the same time. Telling the stories and living in them.

We keep telling stories because we know that the lessons that the Western world supposedly learned after the two world wars are very easily forgotten, and the further we are from global events, the more they become mere statistics. We cannot allow war journalism to become like sports reporting, where only the score matters. We tell the stories of people; we preserve them from oblivion.

We document events, even though it’s hard and painful, to show people the truth so that no one doubts what really happened in Bucha, Mariupol, or in Kharkiv Oblast, where 370 people were found in mass graves.

In 2017, a Russian photographer received one of the World Press Photo Awards for images taken in Ukrainian territory under Russian occupation. Since there were no Ukrainian documentary photographers present, the Russian photographer was able to spread misinformation globally by “omitting” Russian direct involvement in the war in Donbas in his photo captions.

In 2023, the main World Press Photo of the Year Award and the Pulitzer Prize were both given to Ukrainian photographer Evgeniy Maloletka. He, along with his Associated Press team members, was the only one to document Russia’s war crimes in Russian-besieged Mariupol at the start of 2022. These photos shook the world, revealing Russia’s true nature.

We see our mission in speaking up. It’s important to tell our own story, using the pictures of Ukrainian photographers and the columns of Ukrainian intellectuals. When their work in the fields and their texts are seen worldwide, and when a Ukrainian documentary about Mariupol wins an Oscar, this makes a significant contribution to our decolonization process, where we finally have the right to our own voice, and the world is eager to hear it.

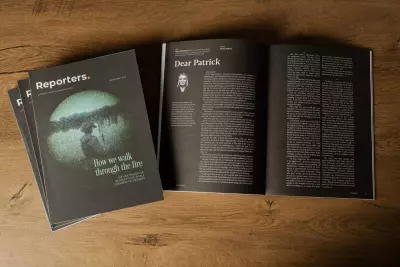

We gathered 155 images of the first months since the full-scale invasion started in a magazine so people could see what has happened to us, to our country, to our people—so we could embody that struggle against oblivion.

Yet, amidst these powerful images, what struck me the most in this magazine was actually a piece of text—a column by Ukrainian writer from Donetsk, Olena Stiazhkina, written as a letter to a friend named Patrick.

She writes: Dear Patrick, I still get scared whenever the Russians are bombing Kyiv. Dear Patrick, you won’t believe it, but right now, me, who hates Russians with cold, deadly passion, I am persuading my friend under occupation to get a Russian passport. Because those who don’t accept Russian citizenship will be sent to a special camp, from which they may never return… At funerals, Patrick, even at funerals, I try to hold myself together. I grip my shoulder tightly, pressing on it so hard it hurts. I do this to appear strong. My left arm is covered in bruises. To avoid explaining this to others or looking like a victim of domestic abuse, I wear long sleeves. I am fifty-five years old. And you, Patrick, are my dear imaginary friend. This is precisely why I invented you—to be able to talk to you, and to explain what’s going on in my country. “

This is what strikes me the most.

So how is “The Ukrainians Media” different from others covering this deadly war?

Our mission is to tell stories fully, to ensure they are understood and shared. The story of this war didn’t start in 2022; it began in 2014, at the same time as The Ukrainians Media, right after the Revolution of Dignity. We’re here to remember this and ensure it’s not forgotten—by you or by us.

We are the heroes of our own stories, and we cannot walk away.

When a missile killed four members of one family not far from our office, in central Lviv, we were horrified by the extent of the grief felt by the father of this family, who lost three daughters and his wife in one moment.

We were horrified, but we also couldn’t be silent. Because maybe their story and others like them could change how other people think about this war—and that this, in turn, might persuade foreign governments to give us the resources and permissions we need—so that we won’t lose any more of our people.

We continue to tell these stories, even when we are hurting and grieving because we believe that sharing them may save someone in the future.

We can’t stop being storytellers; we can’t stop being heroes. We must speak out.

Storytelling doesn’t just need a narrator—it needs an audience. We believe we are not speaking into a void. We trust that all the sacrifices made over these years are not in vain, that the price we’ve paid is worth it, and that truth will prevail.

So we keep telling these stories: recording audio, capturing videos, taking photos, making films, and writing about the war—not just since February 24, 2022, but since 2014. And we do so with one conviction: our readers are not imaginary, like Patrick. They are as real as the heroes whose stories we share.