So much postindustrial attention gets lavished on economic rebounds, neighborhood revitalization, and yes, sports, that we risk missing out on what captures and sparks our collective community imagination: Art, and the arts. Cities should inspire, not simply serve. At its best, that’s the purpose of public art and art in public.

In May, Pittsburgh’s Warhol Museum announced a plan to spend $60 million over 10 years to transform its corner of the North Side into a “Pop District”: an expanded museum and performance space; arts education and training programs for the community; abundant art on public display; and a blocks-wide district of arts organizations, galleries, and associated development.

Nearby, as I wrote last time, the Pittsburgh Steelers have rebranded their stadium with the “Acrisure” name as a signal that technology should rule Pittsburgh’s roost. The folks behind the Pop District say: Not so fast.

It’s not a competition. Pittsburgh is plenty big enough for both visions to flourish. And while Steelers Nation may be cautious about Acrisure, fans have every reason to cheer what the Warhol Museum is up to.

Here’s why — and none of this requires that anyone like Andy Warhol’s art as much as I do — back in 2002, then-Carnegie Mellon University professor Richard Florida published a book titled “The Rise of the Creative Class.” Florida, now based at the University of Toronto and a successful consultant as well as academic, collected data that (he argued) showed that economic growth in U.S. cities was associated with phenomena including a percentage of residents who belong to “the Creative Class” — mostly artists and entrepreneurs. The Creative Class thesis was born (“ambitious cities should attract and retain creatives”) and it has lived a long and influential life.

Was the Creative Class thesis correct? The data are mixed. Maybe a vibrant sector of “creatives” follows, rather than produces, a vibrant city.

That’s not to say that “creatives” and “creativity” aren’t important to all cities. They are. Professional artists and arts communities energize communities in ways different than our other neighbors do. They reassure us in who we are; they push us to be more, or better. Done right, art, especially public art, captures and expresses the diverse souls of a city. And no city can survive for long without it, or wants to.

But trying to identify and recruit “creatives” puts the cart before the horse. Here’s my Pop District-inspired amendment to the Creative Class thesis. The Pop District plan is evidence of a better strategy:

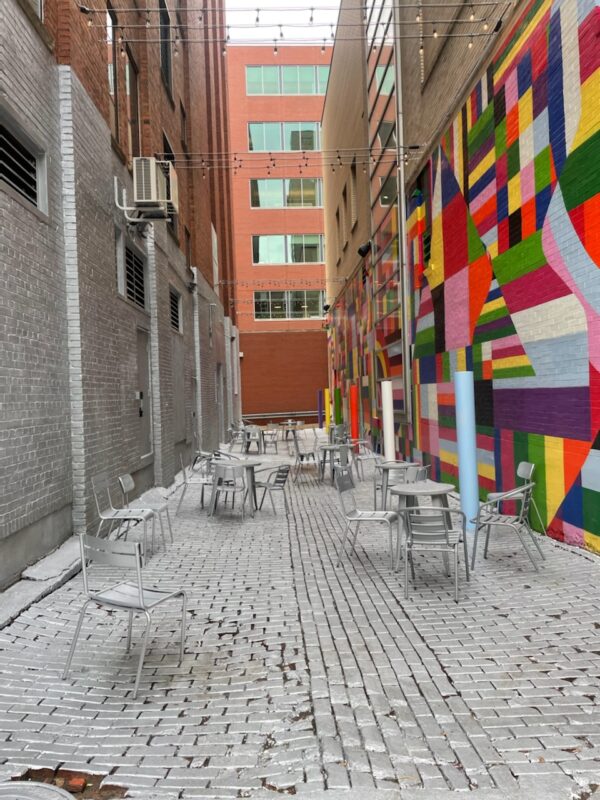

When we’re talking about creative sectors and creative industries, a postindustrial city should focus on supplying infrastructure, not on recruiting or retaining people. Infrastructure means physical spaces — public space, private spaces, and blended spaces — and educational, cultural, financial, and even transportation resources that welcome and encourage art and the arts and people who can see them, hear them, experience them, and even participate in them.

Some of those infrastructures come from the public sector, which can supply money, but more importantly, can supply leadership and coordination. A couple of excellent public projects are in the works right now.

A new Fern Hollow Bridge in Pittsburgh’s East End is on track to be completed by the end of 2022, replacing the structure that collapsed early this year. Thanks to thoughtful planning and procurement supported by the Pittsburgh Art Commission, the completed bridge will include commissioned art, both as part of the bridge’s design and as part of its site, spanning Frick Creek. In August, Allegheny County announced a plan to decorate the Rachel Carson, Andy Warhol, and Roberto Clemente bridges with 600,000 programmable LED lights.

Some of those infrastructures come from nonprofit organizations, like the Warhol Museum itself; from private philanthropy, like the R.K. Mellon and Hillman Foundations, which are footing most of the bill for the Pop District; and even from private companies. Pittsburgh’s Office for Public Art is a beacon and resource coordinating many of their efforts.

Putting “private” anything into the process of producing publicly-accessible art raises potential red flags about the “privatization” of public, collective experience. I’m a cheerleader for the Pop District today, but I’ll be disappointed if it evolves over time into a playground for elite “art world” descendants of Warhol’s vision. The Pop District can count itself a success only if it pushes against the pull of contemporary arts snobbery.

What’s more, true public art — commissioned, installed, and maintained under the supervision of public authorities — is far from bias-free. How Pittsburgh funds public art, via a tax on development of public structures, inevitably pushes more public art into neighborhoods that already have most of it. The full diversity of Pittsburgh artistry rarely has been expressed in the city’s public artworks. And only during the administration of Mayor Bill Peduto (and before the COVID-19 pandemic) did Pittsburgh’s Art Commission abandon its practice of holding public meetings at times and in places that were functionally inaccessible to residents of most Pittsburgh neighborhoods.

In short, making and maintaining infrastructures is a complicated job. But someone has to do it, and it’s the right thing to do. That’s because public art isn’t just about economic development. Public art is an indispensable part of getting all people to pay attention — to each other, to their communities, and to their shared futures.

Pittsburgh has a history of being built and led by small numbers of powerful people. If that’s going to change, we need to find ways to build connection and identity across a broader community, even if those things emerge from debate, rather than from Super Bowl wins or the history of the steel industry.