I never thought I’d say this: I’m glad my mother is dead.

Sounds harsh, but it’s actually a kindness. It has nothing to do with our relationship, but rather the current political climate in the U.S.

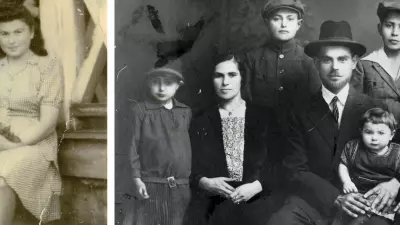

Paula Kreiter, nee Chaya Pola Rozenblum, was born in Radzyn, Poland, May 12, 1927 – actually, we were never sure if it was the 11th or the 12th, but it said 12 on her birth certificate – and was a Holocaust survivor.

She was 11 when Germany bombed her city. She was sitting between her sisters, one older, the other younger. Both were hit by shrapnel and died instantly. My mother was saddled with survivor’s guilt for the rest of her life.

After that she spent time in two ghettos and five concentration camps, including Auschwitz. On arrival at Auschwitz with her brother – the two had been inseparable because they were just 10 months apart – they were separated into lines: she to the left; he to the right. Her brother was in the line that went straight to the gas chamber. In a family of nine, she and her oldest brother were the only survivors – he because he spent the war in Siberia.

So, the rise of anti-Semitism in the United States would have hit her hard. Former President Donald Trump’s early rhetoric about Mexican immigrants would have been mildly worrisome, and she might have agreed with him about banning people from certain Muslim countries. But when he said there were “very fine people” on both sides at the white supremacist march in Charlottesville, Va., she would have started to freak out.

Growing up, there was always the fear that anti-Semitism would raise its head. There were little things, but nothing overt. When John F. Kennedy was assassinated and Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested, the first words out of my father’s mouth were: “Thank God, he’s not a Jew.” I was once at a convention where a salesperson from a competing company said she would try to “Jew down” hotel management about the cost of a hospitality suite. She wasn’t aware that what she had said was offensive.

And I’m not alone in feeling a change.

Lane Rubenstein was born in Wolomin, Poland, a small town with a Jewish population of 2,000 just a few miles from Warsaw in 1935. He remembers what he and his family went through during the war. He was among the lucky ones, hidden by Polish neighbors who risked their own lives.

As a child he saw Germans march into his town. He saw attacks on Jews just walking down the street. He saw people forced out of their homes and into a ghetto. He saw the ghetto emptied, people loaded onto boxcars and transported to Auschwitz. He spent 2½ years lying on his belly, hidden in a crawl space with his family.

After the war, he saw Jews chased out of Poland.

After spending more than a dozen years in Israel, where he served as an officer in the Israeli army, Rubenstein’s brother talked him into immigrating to the United States.

“I cannot believe what has happened to America. I cannot believe this could happen to a country like this,” Rubenstein said. “I came to America [in 1964] and people were friendly and nice. No one talked about anti-Semitism.

“[But] I see it here, and I’m afraid of the same thing happening [that happened in Europe]. The environment has completely changed.”

Chicago police statistics indicate the number of hate crimes against Jewish targets rose from eight in 2021 to 38 in 2022. Across the Midwest, they’re up 44%. Then, there was the deadly attack on the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh in 2018 and the hostage-taking at Beth Israel in Colleyville, Texas, last year.

In Washington, President Biden appointed Deborah Lipstadt as his anti-Semitism envoy and laid out a strategy for combating the increasing level of hate. Rep. Lauren Boebert, R-Colo., immediately took issue with the action, tweeting that Biden’s plan is an attack on conservatives. Huh? Being anti-Semitic is a right?

The Chicago Tribune reported (May 24) that leaders of Chicago’s Jewish communities brought the issue up ahead of the new City Council’s first meeting.

“Anti-Semitism, fueled by hatred and ignorance, is a stain on humanity’s conscience, and we must confront it head on with unwavering resolve,” Alderwoman Debra Silverstein, who represents the heavily Jewish 50th Ward, told reporters.

New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft said via Zoom he never would have believed he’d see “neo-Nazis raising swastikas and demonstrating. This is the United States of America in 2023. There’s no room for hate.”

There are nearly 16 million Jews worldwide, about 0.2% of the 8 billion people on this planet. In the U.S., the number is around 6.5 million, about 2.1% of the total population. How then, have Jews gotten the reputation that they are in control, manipulating the levers of power?

In European countries, Jews were stripped of their belongings on a regular basis. Countries barred them from owning land. Pogroms were a regular occurrence. So, they turned to businesses that could be packed up in a second if they had to flee.

Sure, there are some Jews in prominent roles: Rahm Emanuel, former congressman, former chief of staff to Barack Obama, former mayor of Chicago and current ambassador to Japan; numerous entertainers and actors – especially comedians like Mel Brooks, Jerry Seinfeld, and Sarah Silverman; those who have accumulated wealth like George Soros and the Rothschild family. But for the most part, the vast majority of Jews just try to live normal lives.

Most wealth and power is held by non-Jews. So, stop trying to blame us.