My nightmares about Iraq come about once a month. They’re one of the “benefits” of my 2004-05 deployment with an Army combat arms unit.

These nocturnal angst-fests present themselves in a few forms. Most commonly, I’m left behind as the convoy drives off into the night, leaving me alone in an Iraqi city. There also are general anxiety dreams where I can’t find my helmet, ammo, or some other critical component of my combat load.

My experiences are not uncommon. I’ve spoken with other veterans about their dreams and even have asked some pointedly, “So, how are your nightmares?”

Such nightmares are one of the more subtle effects of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), the manifestations of which can run a gamut from nightmares to fear of crowds to substance abuse to even suicide.

The National Center for PTSD notes that about 11% to 20% of Iraq and Afghanistan vets exhibit symptoms of PTSD (versus 6% for the general population).

A 2004 study in the New England Journal of Medicine stated that 26% of combat troops who returned from Iraq and/or Afghanistan suffer from some mental health disorder.

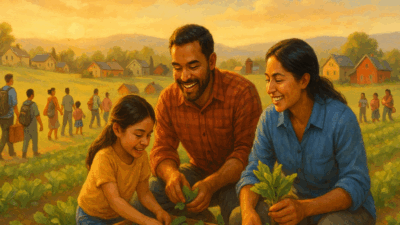

To help address PTSD (and other traumas, including traumatic brain injury and military sexual trauma), there was a groundswell of organizations founded in the early 2000s built around a belief that veterans could find healing through outdoor recreation.

“The proliferation of outdoor programs then was problematic, in part, because few of us were working together,” said Stacy Bare, the former director of Sierra Club Outdoors, which included a military program. “And it seemed like every week someone would say they’re starting another nonprofit.”

Bare describes a rather tantalizing environment in which veterans could access funding, develop an organization built around their own passions, get a bit of a personal spotlight, and maybe even help other vets along the way.

“Many of us said, ‘I’m a vet, listen to me, and give me your dollars.’ And funders said, ‘OK.’ But we didn’t have a way of verifying programs or proving what we said was happening, was actually happening. We missed an opportunity to build stronger, healthy institutions with better veteran engagement,” Bare said.

Today, there are an array of outdoor therapy organizations for veterans — focused on hiking, biking, hunting, fly-fishing, skiing, rock and ice climbing, deep sea fishing, whitewater rafting, surfing, horseback riding, mountain biking, and SCUBA diving.

There are national programs hosted by organizations such as Outward Bound and The Izaak Walton League, and hyper-local ones started on the fly by individual vets. Most provide services to veterans for free — and usually cover travel expenses.

There are organizations that offer day trips, weeklong trips, and at least one, Warrior Expeditions, that will help fund months-long trips to bike across the nation or hike the Appalachian Trail.

While he notes that the overall initiative to get vets into outdoor therapy programs is overwhelmingly positive, Bare calls out an uglier side to some of the organizations, including those that didn’t operate with insurance or secure appropriate permits.

Many provided a multi-day experience, pushing vets to open up about their personal traumas, and then sent them home without any sort of plan for follow up, for example.

“Back then, there were no standards,” notes Kate Dobbie, executive director of Higher Ground. “We liked to say that there were ‘big hearts, bad practices.’ Many of these organizations had a lot of funding, but they were really only providing assisted vacations.”

Over the years, organizations such as Dobbie’s evolved to become more focused on developing strategies to positively impact veterans’ health, through outdoor recreation therapy.

Higher Ground’s trips are limited to eight to 10 veterans and are generally staffed with a recreation therapist, a staff member who is a veteran, and a mental health professional.

They engage in six to seven hours of outdoor activity, then do 90 minutes based on a theme of the day, such as “Healing Tools” or “Building Bonds.”

Many organizations now work with mental health professionals to try to provide proof that their programs are effective in decreasing the manifestations of PTSD in veterans.

For example, Warrior Expeditions works with two psychologists (both veterans) to administer pre- and post-trip surveys to measure symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, depression, and seven other mental health conditions in the vets they serve.

Eventually some organizations saw a need for both establishing standards and working together, setting the stage for the development of an association focused on the needs of these nonprofits.

Now, the Four Star Alliance, an initiative of America’s Warrior Partnership, counts more than 60 of these organizations as members. Each organization must agree to abide by a set of standards and is vetted for financial stability, business practices, and appropriate referrals.

“There are a lot of great programs out there, but they are often at capacity,” said Kaitlin Cashwell, director of community integration for America’s Warrior Partnership. “We’re trying to raise awareness of the great work provided by existing programs, to increase capacity through collaboration, and to demonstrate impact by providing them information about evaluation.”