The flood that ruined Olena Lytvynenko’s home added more misfortune to a life fractured by war.

The misery began with Russia’s invasion in early 2022 that brought death and destruction to the Mykolaiv region of southern Ukraine, where she lives with her husband and two children. Three weeks later, enemy troops occupied their village of Yuriivka, imposing a climate of fear with house searches, arrests and interrogations.

The Ukrainian military liberated Mykolaiv that fall, and in the ensuing months, the sense of dread lifted as Yuriivka regained its bearings – until the flood last June. After Russian forces blew up the Kakhovka Dam on the Dnipro River, the rising water submerged dozens of villages and towns in Mykolaiv and the adjacent Kherson region, displacing 40,000 people.

The Lytvynenko family fled to a relative’s house. When the water receded, they returned home to find the interior beyond salvaging. The few items they had packed before evacuating now accounted for almost everything they owned.

Two months after the disaster, Lytvynenko, 45, guided me through her damaged house. Floodwater had gnawed through the drywall, exposing the bricks beneath, and only the dirt foundation remained of the floor. A shortage of construction materials throughout Ukraine had stalled the family’s rebuilding plans, forcing them to stay with in-laws indefinitely.

Lytvynenko had ample reason to lament her own and the country’s plight. Yet like nearly all the Ukrainians I’ve encountered during the past two years, she appeared immune to defeatism even when beset by personal loss. She instead voiced belief that her family and her besieged homeland would persevere — a conviction born of the shared suffering that Ukrainians present and past have overcome.

“I think that these tragedies unite us because of how our history lives inside us,” she said. “We understand — without saying it — that we will survive, the same as our parents and grandparents survived. It is like a national code.”

Their generational resolve has been on my mind as Ukraine confronts ever more discouraging news on and off the battlefield. The new year began with Russia launching massive missile and drone strikes on Kyiv and other cities across the country, killing dozens of civilians. The attacks occurred a month after Congress and the European Union failed to approve military aid packages for Ukraine worth a combined $115 billion.

Mired in a stalemate as the war’s two-year mark approaches, Ukrainian troops face dwindling supplies of munitions and mounting casualties while the army scrounges for new recruits and corruption plagues the defense ministry. Growing pessimism in the West about Ukraine’s chances of victory has amplified a pundit chorus urging President Volodymyr Zelensky to seek a ceasefire and cede land that Russian forces control.

But such unsolicited advice ignores the popular sentiment of Ukrainians, nearly 90% of whom still believe the country will prevail. Their hard-earned faith derives, in part, from lessons bequeathed by earlier generations who withstood Russian tyranny as far back as the 17th century.

A defiant solidarity

The people I met in Yuriivka and the nearby settlement of Afanasiivka embodied the steadfastness that lies at the heart of Ukraine’s legacy of persistence. In the aftermath of the flood that swallowed both villages – and claimed untold lives in Russian-occupied areas – residents reacted with equal disdain to the impulse of self-pity and the suggestion of surrender.

“What will change if we’re angry? If we’re sorry for ourselves?” asked Olga Yanevych, 36, as she stood inside her hollowed-out home in Afanasiivka. “We have to adapt – as a family, a community, a nation.”

Water engulfed the two-bedroom house up to the eaves after she and her husband escaped with their two children. The couple decided to gut the space, and the renovation would take months while the family lived with her parents in another town.

Growing up, Yanevych listened to her grandparents describing the anguish of the Holodomor, the man-made famine that Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin inflicted on Ukraine in the 1930s that killed 4 million to 10 million people. One of her grandfathers, forced to serve in the Red Army during World War II, instilled in her a distrust of Moscow long before Russian President Vladimir Putin launched his full-scale invasion.

“All of us know the history of what Russia has done to Ukraine,” Yanevych said. “Now we are going through the same history.” She recalled Russian soldiers entering her family’s home soon after occupying the Mykolaiv region. One pointed at the microwave and told her husband, “Open the safe.”

“The Russians have no education. It’s like they grew up in medieval times,” Yanevych said. “They want to drag us backward to the Soviet Union.”

Putin’s war of choice against Ukraine began 100 years after Russian leader Vladimir Lenin annexed the smaller nation and formed the Soviet Union in 1922. Stalin succeeded Lenin in 1924, and in addition to the millions he starved, he consigned millions more to death through forced labor, mass purges, and military conscription during his decades-long reign.

Ukraine broke out of Moscow’s iron grip and gained its sovereignty after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. The brutality, privations, and absence of personal and political freedom that defined the Soviet era remained vivid in the country’s collective memory when, only three decades later, Russian forces again invaded.

Their return provoked a defiant solidarity among Ukrainians that sustained residents in Yuriivka and Afanasiivka during the Russian occupation and after the flood.

Vasyl Khomko, head of the village council that represents both settlements, lived his first 31 years under the Soviet regime, watching as the idea of an independent Ukraine morphed from faint mirage to vibrant reality.

“This is a terrible war,” said Khomko, 64, as we sat in his peach-colored office inside the village hall. A wall map above his desk showed every property in the two towns, where the combined population of 1,900 fell by more than half after the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam. “But we know it still is better than being controlled by Russia.”

Starting in the 1600s, Russian czars seized ever-larger portions of Ukraine and attempted to terrorize its people into submission. The Kremlin’s oppression of the country extended through the Soviet Union, and the desire to prevent a revival of that dark history fortifies Ukrainians in their struggle against Putin, who rose to power in 2000.

“Russians have raped us, killed us, destroyed our homes and cities for centuries,” Khomko said. “So, we understand these feelings of invasion and occupation already because of what our ancestors went through. It’s in our DNA.”

“We will survive Russia”

Most of Ukraine’s 44 million people either grew up during the Soviet period or were born to parents who endured its gray, grim austerity and culture of suspicion. The experience has given older Ukrainians — unlike Western analysts calling for Zelensky to capitulate — a visceral awareness of what their country would lose if Russia triumphs.

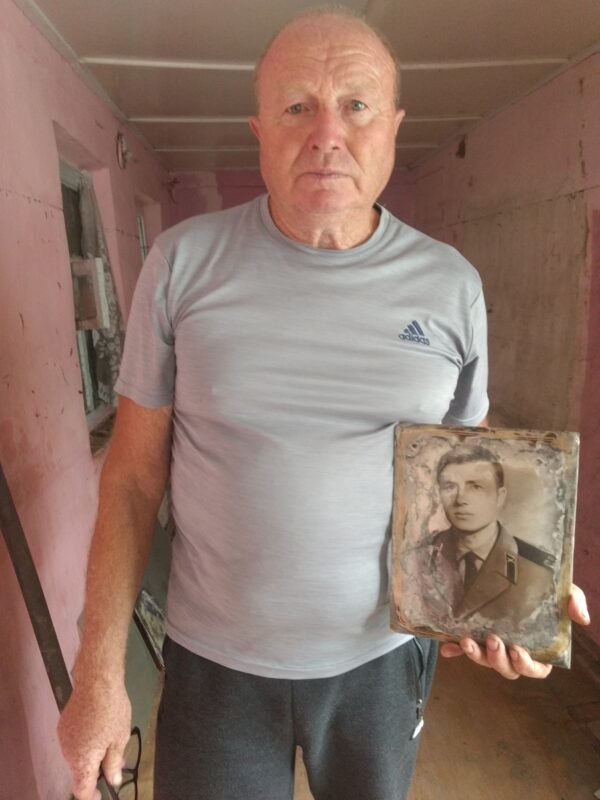

Following the flood, Mykola Tiupalo, 70, sifted through his sodden possessions in his home in Yuriivka. He recovered a black and white portrait of himself as a young conscript in the Soviet army in the early 1970s. He had chafed at serving on Moscow’s behalf, and a half-century later, he shared with quiet pride that his son and grandson wear the uniform of the Ukrainian military.

“We did not want war,” he said, standing amid the rubble of his family room. “But our young people have grown up in a free country, and they have learned from those of us who didn’t, that Ukraine is not part of Russia.”

In 2014, Putin annexed Crimea and dispatched military operatives to lay claim to a swath of the Donbas region in southeastern Ukraine. The siege bewildered Tiupalo at first. “It was hard to understand that the Russians were attacking us,” he said. “When I realized what was happening, I knew they wouldn’t stop.”

The United States and the West offered a tepid response to Putin’s aggression a decade ago, and undeterred, he chose to unleash war on all of Ukraine in 2022. In Yuriivka and Afanasiivka, as across the country, destroyed houses and the sudden absence of loved ones testifies to the toll of the West’s hesitation.

Early in the invasion, Lyudmila Mavrych recalled, Russian troops searched door to door in both towns for military veterans who fought in the Donbas in 2014. The soldiers detained two Ukrainian men and drove off. Their families had since heard nothing from them.

“All my life I never hated anybody,” said Mavrych, 60, an administrator with the village council. “Now I hate an entire country.”

The flood last summer ravaged the home that she and her husband built in Afanasiivka in 1982. The couple lost furniture, family heirlooms, and most everything else. I walked with her through the debris, and as we entered the living room, she picked up a framed icon that somehow had eluded the water’s reach.

The religious painting has belonged to her family for more than 100 years, predating the Soviet Union. Mavrych viewed its durability as symbolic of the Ukrainian people and their refusal throughout history to surrender to Moscow.

“We survived the invasion, then the occupation, then the flood,” she said. “We will survive Russia.” She paused for a moment before adding a final thought that she wanted me to bring back to America.

“We have a strong spirit. What we need are weapons.”