Keeps a sharp look out for sabotage,

Sitting up there on the fuselage,

That little frail can do,

More than a male can do,

Rosie (brrr) the Riveter.

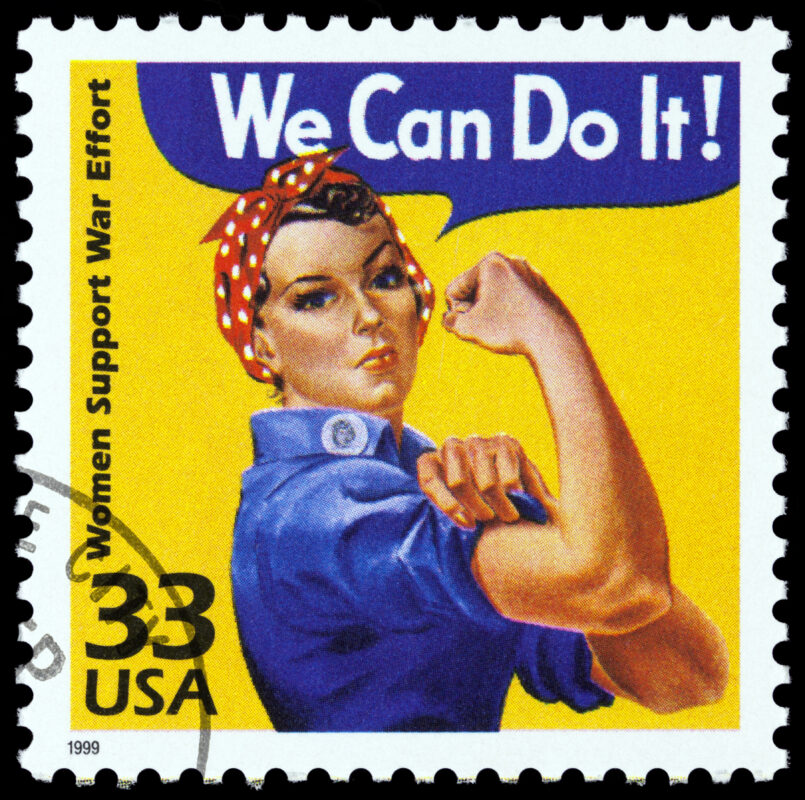

— “Rosie the Riveter” song, 1942

The World War II generation grows smaller with every year, but many nonagenarians — including real-life Rosie the Riveters, the women who helped America win the war by taking over factory jobs vacated by men fighting the war overseas — still cherish and share their memories of their work in the 1940s.

An estimated 5 million to 7 million women held war industry jobs during World War II. Living Rosies have a reason to be especially proud of their work now. However it wasn’t until 2020 that they received formal recognition, with the Congressional Gold Medal Act.

Three Rosies shared their memories with Postindustrial.

Florence “Flo” McCarty, 97

Livonia, Mich.

Though some memories of working at the Willow Run B-24 bomber plant may have faded, Florence “Flo” McCarty will never forget how it felt to work there.

In 1942 and early 1943, McCarty worked the afternoon shift at Willow Run, where she toiled in the plane’s fuselage as a hydraulic assembler — a difficult job that paid a paltry $1 per hour.

“It seemed OK then,” McCarty said about the low wage. She left her job as a lawyer’s secretary to work in the factory.

McCarty’s job was physically grueling, because she had to curl her feet up under her to get close to the side of the plane and install hydraulic lines that operate brakes and other functions. These functions are crucial to the plane’s safe operations and McCarty — who wore the jumpsuit and bandanna to protect her hair — knew she had lives in her hands.

“I used to sit there and say, ‘Oh, this has got to be perfect,’” she said. “I had to do a good job.”

McCarty doesn’t remember the men taking the women in the factory too seriously. Then again, there weren’t many men there, because so many of them were off fighting the war.

She was married to her husband David, who also worked at the factory on the same shift, when she worked at Willow Run, but they did not have children yet.

They got married in 1942. She recalls climbing on the back of her husband’s motorcycle, wrapping her arms around his waist, and riding together to work. They often stopped to eat at the Bomber Restaurant, which is still open and serving folks in Ypsilanti, Mich.

Flo McCarty left her Willow Run job in 1943 to join the U.S. Navy Hospital Corps as a nurse’s aide; at the same time, David McCarty joined the Army before he got inevitably drafted. Husbands and wives couldn’t serve in the same branch, so she chose the Navy and enlisted for two years. Flo McCarty attended boot camp in Bronx, N.Y., and served her Navy time at the Naval Station Great Lakes in Illinois.

After the war ended, Flo McCarty spent the rest of her pre-retirement years in the workforce as a secretary; her husband worked in heating and air-conditioning.

She looks back fondly on her service to the country, both as a Rosie and at Willow Run in the 1940s, and knows how crucial it was for America’s victory in World War II.

“I think it was very important,” she said. “We like to think that, anyhow.”

Her Rosie the Riveter role has been a big part of her life, and not just during the war. She regularly attends potlucks for Rosie alumnae and has made friends with women in her area. McCarty was thrilled to hear about the Congressional Gold Medal awarded to Rosie the Riveter in December of 2020.

“I thought it was wonderful,” she said. “It was quite a tribute.”

Marjorie Haskins, 98

Saline, Mich.

It seems pitiful today, but Marjorie Haskins’ $1-an-hour pay at Willow Run factory near Ypsilanti, was an improvement over the $17 a week she was making working full-time hours at a five-and-dime store prior to World War II.

Still, Haskins wasn’t too concerned about money. She jumped at the chance to serve her country at Willow Run, a plant constructed in 1941 by the Ford Motor Company to build B-24 Liberator bombers for the military.

“I figured I was helping to make things to get the boys back home again,” said Haskins, who began the Willow Run job in 1942 at age 19 and stayed through the end of the war. “I thought I was doing a job that would help to win the war.”

“I thought I was doing a job that would help to win the war.”

Haskins didn’t work on the assembly line, where she remembers workers making an entire plane from scratch in about an hour. She worked in a “crib” — similar to a modern-day cubicle — located in the area of the big, loud metal presses that made several parts of the plane. People seeking parts would approach Haskins, who would look the part up in a catalog and then tell them where it was located.

She recalls older, male colleagues treating her nicely during her time at Willow Run, when she carpooled with friends because gas was rationed. She remembers one particular man at work who made her a bracelet out of scrap metal — with the word “Marge,” her nickname, stamped into it and the numbers 19 and 43 at each end to depict the year.

When Haskins started her job, she wasn’t married — but she married Gordon Haskins, whom she had known since she was a kid, while employed at Willow Run. Her husband was in the Coast Guard and worked internationally on a ship that carried tanks and troops.

When the war ended, Marjorie Haskins was one of the last Willow Run women to lose her job, because of her role locating parts. She enjoyed her job, but she wasn’t disappointed that it ended because of the trade-off: It meant the terrible war was over and her husband was coming home.

Gordon and Marjorie Haskins were married for 61 years, and they had one daughter, Linda. After the war, Marjorie Haskins stayed in the workforce, with jobs including at an automobile plant. Later, she and her husband bought a hardware store. She made many female friends at the factory and attended Rosie reunion events over the years, and she still talks to and sees some of those friends.

Haskins looks back fondly on her years as Rosie the Riveter, and recognizes the significance of her and her comrades’ role in American history.

“I’m just glad that I was able to work and do things like that to bring the boys home,” Haskins said.

Mae Krier, 95

Levittown, Pa.

Only a tiny portion of Mae Krier’s Rosie the Riveter career was spent actually working at the Boeing factory in Seattle, building planes from 1943 through 1945. The Philadelphia-area woman has spent some four decades advocating for the proper recognition of her Rosie cohorts while many are still alive to appreciate it.

One could argue that Krier is the top living Rosie the Riveter ambassador. Her promotion efforts over the years, including lobbying lawmakers, played a big role in securing the Congressional Gold Medal.

“Getting the medal was so important, but what was most important was the journey getting there,” Krier said. “The things you value the most in life are the things you work the hardest for.”

“I guess I would describe myself as being determined. I just wanted to see that the women were recognized for what they did before I met my maker.”

Krier was just 17 when she, a sister, and a friend left their homes in North Dakota for the Boeing factory in Seattle, where they made B-17 and B-29 warplanes. Only men had those types of jobs before the war, and the presumption was that only men could do those jobs adequately.

“Oh gosh, we sure showed them,” Krier said. “Up until 1941, it was a man’s world. They didn’t know how capable American women were. … Some of us were better than the men.”

Yet, after the war ended, the women lost their jobs to the returning men.

“The men came home to flying flags and parades. Rosie came home with a pink slip,” Krier said. “It wasn’t fair because they couldn’t have won the war without us.”

Over the years, Krier has participated in numerous events to honor Rosie the Riveter and other historical occasions, such as the D-Day anniversary. She travels often, meeting intriguing characters along the way and politicians including U.S. Sen. Bob Casey.

Meanwhile, she used her crafty talents to make bandannas — and then, in 2020, face masks for the pandemic — in the iconic white polka dots on red as depicted in the ubiquitous “We Can Do It!” image.

Undoubtedly, Rosie the Riveter became a lifetime part of Krier’s identity and mission.

“I guess I would describe myself as being determined,” she said. “I just wanted to see that the women were recognized for what they did before I met my maker.”

Dorothy Schrag, 96

Sun City, Arizona

Originally from Canton, Ohio

Dorothy Schrag had just graduated from high school in 1943 and was planning on attending college, but she put her plans on hold to serve her country by working at Republic Steel and building B-24 Liberators.

At this steel plant in Canton, Schrag took the bus across town along with at least a dozen other Rosies each day to work the late-night shift, which ran 4 p.m. to midnight, because it paid more. It seemed like the right thing to do, since all the men she knew – including her boyfriend and future husband, Charles Arthur Schrag, who joined the military to fly B-17s – were either getting drafted or enlisting to fight the Germans or Japanese.

The U.S. Air Force wasn’t officially formed as its own branch of the military until 1947, and in building fancy warplanes, “we just really had to play catch-up,” Schrag said.

Schrag worked as a buffer who would hold the wing still while the riveter on the other side installed the rivet. Both workers would shake as the rivets were installed, making the wings vibrate, and Schrag’s job was to hold the wing to stabilize it. It was very challenging physically and demanding, she recalls.

“When the inspector would come by and look, even one mark off would damage the metal,” Schrag said. “You had to develop a steadiness … and just the muscle work. It was exhausting.

“We were so dedicated to rallying ourselves to make this thing work for our boys who had … left their careers to go over and defend us. It was just a rallying spirit.”

“I didn’t have a social life at all,” she remembered. “I came home and was so tired. I never missed a day of work. … Whatever was required, I went along with it.”

Schrag recalls older women taking her under their wing, so to speak, and treating her very well. The men also showed Schrag and her female coworkers respect, and they earned it, she said.

“We were so dedicated to rallying ourselves to make this thing work for our boys who had … left their careers to go over and defend us,” Schrag said. “It was just a rallying spirit.”

Schrag worked for a year at the factory, and then gave notice and went to Wittenberg University; after that, she enjoyed a fulfilling career as a teacher of kids in grades 4 to 6. Meanwhile, Dorothy and Charles Arthur Schrag, who met in their church youth group, married, and went on to have two sons. Dorothy Schrag, now widowed, has three grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

Her Rosie identity became a big part of Schrag’s life, which she now lives in a senior-living community in suburban Phoenix. On Memorial Day, a band from Luke Air Force Base plays, and a member asks: “Are there any Rosie the Riveters in the audience?”

For a while, there were three Rosies there. Then, there were two. And now, Schrag is the only one left.

“People say, ‘Did you really do that?’” Schrag said. “I say, ‘Yes I did.’ I’m a patriot. I’m still alive.”