ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

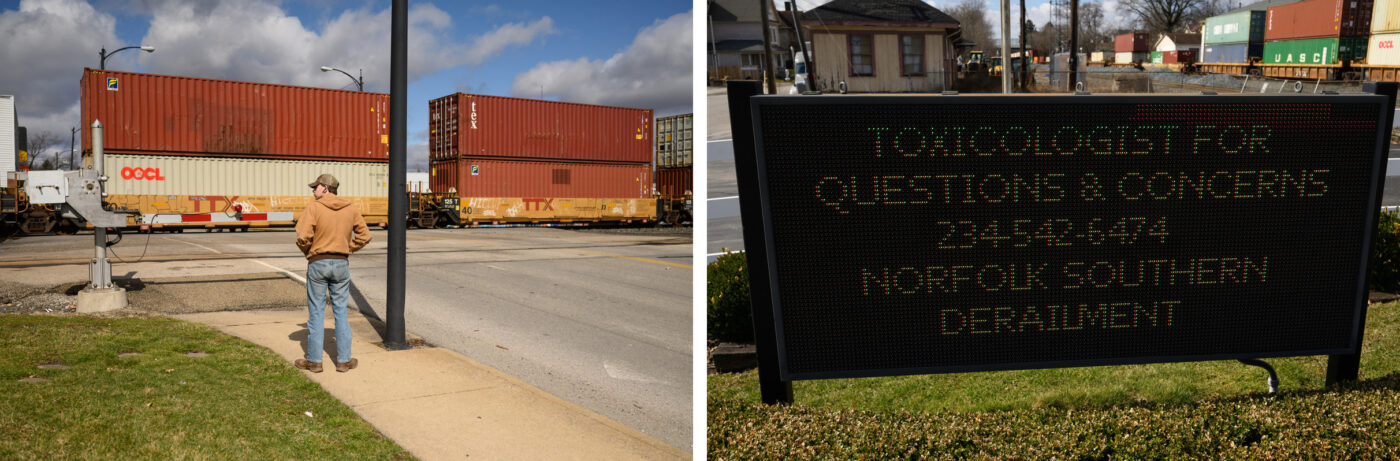

Last month, Brenda Foster stood on the railroad tracks at the edge of her yard in East Palestine, Ohio, and watched a smoky inferno billow from the wreckage of a derailed train. The chemicals it was carrying — and the fire that consumed them — were so toxic that the entire area had to evacuate. Foster packed up her 87-year-old mother, and they fled to stay with relatives.

With a headache, sore throat, burning eyes and a cough, Foster returned home five days later — as soon as authorities allowed. So when she saw on TV that there was a hotline for residents with health concerns, she dialed as soon as the number popped up on the screen.

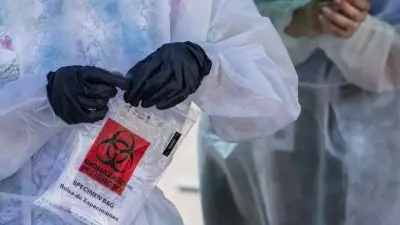

The people who arrived offered to test the air inside her home for free. She was so eager to learn the results, she didn’t look closely at the paper they asked her to sign. Within minutes of taking measurements with a hand-held machine, one of them told her they hadn’t detected any harmful chemicals. Foster moved her mother back the same day.

What she didn’t realize is that the page of test results that put her mind at ease didn’t come from the government or an independent watchdog. CTEH, the contractor that provided them, was hired by Norfolk Southern, the operator of the freight train that derailed.

And, according to several independent experts consulted by ProPublica in collaboration with the Guardian, the air testing results did not prove their homes were truly safe. Erin Haynes, a professor of environmental health at the University of Kentucky, said the air tests were inadequate in two ways: They were not designed to detect the full range of dangerous chemicals the derailment may have unleashed, and they did not sample the air long enough to accurately capture the levels of chemicals they were testing for.

“It’s almost like if you want to find nothing, you run in and run out,” Haynes said.

About a quarter century ago, the Center for Toxicology and Environmental Health was founded by four scientists who all had done consulting work for tobacco companies or lawyers defending them. Now known by its acronym, CTEH quickly became a go-to contractor for corporations responsible for industrial disasters. Its bread and butter is train crashes and derailments. The company has been accused repeatedly of downplaying health risks.

In since-deleted marketing on its website, CTEH once explained how the data it gathers about toxic chemicals can be used later to shield its clients from liability in cases brought by people who say they were harmed: “A carrier of chemicals may be subjected to legal claims as a result of a real or imagined release. Should this happen, appropriate meteorological and chemical data, recorded and saved … may be presented as powerful evidence to assist in the litigation or potentially preclude litigation.”

Despite this track record, this company has been put in charge of allaying residents’ concerns about health risks and has publicly presented a rosy assessment.

It was CTEH, not the Environmental Protection Agency, that designed the testing protocol for the indoor air tests.

And it is CTEH, not the government, that runs the hotline residents are directed to call with concerns about odors, fumes or health problems. Local and federal officials, including the EPA, funnel the scared and sick to company representatives.

In a statement, Paul Nony, CTEH’s principal toxicologist and senior vice president, said the company has responded to thousands of incidents, and its environmental monitoring and sampling follows plans approved and directed by the incident commanders of each response. “Our highly skilled, certified specialists include Ph.D. toxicologists, masters in public health, industrial hygienists and safety professionals, as well as hazardous materials and registered environmental managers,” he wrote.

He added that CTEH has been “working side-by-side” with the EPA in East Palestine “and comparing data collected in the community and in people’s homes to ensure that we are all working with the most accurate data.” Hotline callers receive information, Nony wrote, that is “based on the latest data collected by CTEH and EPA, vetted together to ensure the accuracy of the public health information provided.”

The circumstances of the testing are unclear. The EPA said its representatives have, indeed, accompanied CTEH to residents’ homes, overseen the company’s indoor air tests and performed side-by-side testing with their own equipment. But some residents told ProPublica that even though multiple people came to their doors, only one person had measuring equipment. An agency spokesperson said CTEH’s testing protocol “was reviewed and commented on by EPA and state and federal health agencies.”

Stephen Lester, a toxicologist who has helped communities respond to environmental crises since the Love Canal disaster in upstate New York in the 1970s, said he was concerned about Norfolk Southern’s role in deciding how environmental testing is done in East Palestine. “The company is responsible for the costs of cleaning up this accident,” Lester said. “And if they limit the extent of how we understand its impact, their liability will be less.”

An EPA spokesperson said that the federal blueprint for responding to such emergencies requires responsible parties, in this case Norfolk Southern, to do the work — not just pay for it. But the agency has the authority to perform or require its own testing.

The relationship between CTEH and Norfolk Southern wasn’t clear to several residents ProPublica interviewed. Before testing begins, people are asked to sign a form authorizing the “Monitoring Team,” which the document says includes Norfolk Southern, “its contractors, environmental professionals, including CTEH LLC, and assisting local, state, and federal agencies.” An earlier version of the form included a confusing sentence that suggested that whoever signed was waiving their right to sue. Norfolk Southern said that was a mistake and pulled those forms.

In a written response to questions, Norfolk Southern said it “has been transparent about representing CTEH as a contractor for Norfolk Southern from day one of our response to the incident.” The company also pointed to a map on its website displaying CTEH’s outdoor air-monitoring results that says “Client: Norfolk Southern” in tiny type in the corner. “We are committed to working with the community and the EPA to do what is right for the residents of East Palestine,” a Norfolk Southern spokesperson wrote in an email.

When told by a reporter that the contractor, CTEH, was hired by the rail company, Foster’s face fell. “I had no clue,” she said. Looking back, she said, the people who came to her door never said anything about Norfolk Southern. They didn’t give her a copy of the paper that she had signed.

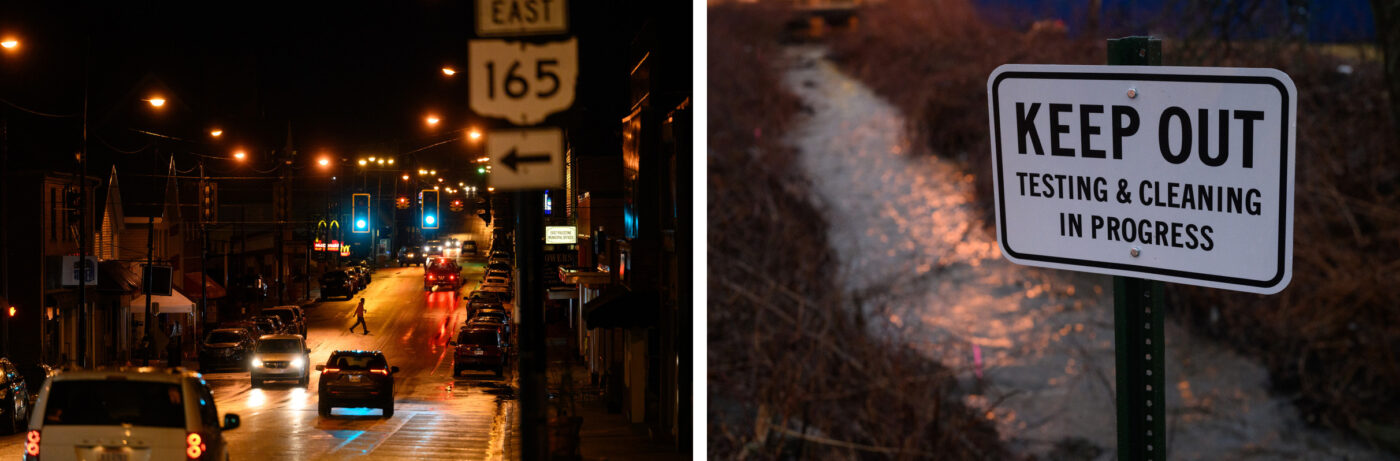

Before the derailment, East Palestine offered its 4,700 residents some of the best in small-town life. Its streets are lined with trees and charming houses. After school, kids played in the street, in the well-maintained park or in its affordable swimming pool. At Sprinklz on Top, a diner in the center of town, you can get a full dinner for less than $10.

Everything changed after the Feb. 3 derailment and the subsequent decision to purposefully ignite the chemicals, sending a toxic mushroom cloud over the town. Dead fish floated in local waterways, and “Pray for EP” signs appeared in many windows. Furniture is piled up on the curbs. Foster said some of her neighbors are replacing theirs because of concerns about contamination. But the 57-year-old, who works shifts painting firebrick, says she doesn’t have the money to do that. So she has come up with a solution she hopes will reduce her exposure: She sits in a single chair.

Tests May Miss Some Dangers

From the earliest days of the disaster, CTEH’s work has been at the center of the rail company’s reassuring messages about safety. Norfolk Southern’s “Making it Right” website cites CTEH data when stating that local air and drinking water are safe. (An EPA spokesperson said the agency has not “signed off” on any of Norfolk Southern’s statements “with regard to health risks based on results of sampling.”)

A video posted on Norfolk Southern’s YouTube account shows footage of a man in a CTEH baseball cap looking carefully at testing machinery. “All of our air monitoring and sampling data collectively do not indicate any short- or long-term risks,” a CTEH toxicologist says.

According to the EPA, CTEH’s indoor air testing in East Palestine consists of a one-time measurement of what is known as volatile organic compounds, or VOCs. These airborne chemicals can cause dizziness and nausea, and, over the long term, some VOCs can cause cancer. Vinyl chloride, a VOC that was carried by the derailed train and later ignited, can cause dizziness and headaches and increase the incidence of a rare form of liver cancer, according to the EPA. The machine that CTEH uses in East Palestine captures VOCs if they’re above 0.1 parts per million, but it doesn’t say which specific compounds are present.

CTEH said that when VOCs are detected, the company then tests for vinyl chloride. According to the EPA, the indoor testing has detected VOCs in 108 buildings before Feb. 21 and 12 buildings after that. Follow-up tests found no vinyl chloride, according to CTEH and the EPA. CTEH’s Nony said, “CTEH has not considered conducting long-term VOC air sampling in the homes because real-time air monitoring results do not indicate a significant impact of VOCs related to the derailment in the homes.”

But five experts on the health effects of chemicals consulted for this story said that the failure to detect VOCs should not be interpreted to mean that people’s homes are necessarily safe.

“VOCs are not the only chemicals that could have been in the air,” said Haynes, the environmental health professor. Haynes also said that because the testing was a snapshot — as opposed to an assessment made over several days — it would not be expected to detect VOCs at most household levels.

Many of the toxic chemicals that were airborne in the early days after the derailment, including pollutants that can cause cancer and other serious problems, may have settled out of the air and onto furniture and into crevices in houses, Haynes said. So she also recommended testing surfaces for compounds that could have been created by the burning of vinyl chloride, such as aromatic hydrocarbons, including the carcinogen benzene. Young children who play on the floor are especially vulnerable, Haynes added.

Even a week after the derailment, Haynes said VOCs likely would have dissipated. “To keep the focus on the air is almost smoke and mirrors,” she said. “Like, ‘Hey, the air is fine!’ Of course it’s going to be fine. Now you should be looking for where those chemicals went. They did not disappear. They are still in the environment.”

In addition, Dr. Ted Schettler, science director at the Science and Environmental Health Network, noted that some VOCs can cause symptoms at levels below 0.1 parts per million, which CTEH’s tests wouldn’t capture. Schettler gave the example of butyl acrylate, one of the chemicals that was carried by the derailed train. “The symptoms are irritation of the eyes and throats, headaches and nausea,” he said.

In its statement, Nony acknowledged that some homes in East Palestine had the odor of butyl acrylate, but he said that “current testing results do not indicate levels that would be associated with health effects.”

Health experts are particularly concerned about dioxins in East Palestine because the compounds can cause health problems, including cancer. The combustion of vinyl chloride and polyvinyl chloride, two of the chemicals that were on the train and burned after it derailed, have been known to produce dioxins.

But, in his statement, Nony dismissed the idea that the incident could have created dioxins “at a significant concentration” and said testing for the compounds was unwarranted. The company based that assessment on air monitoring it did with the EPA when the chemicals were purposefully set on fire; they were looking for two other chemicals that are produced by burning vinyl chloride.

Last week, the EPA said it would require Norfolk Southern to test for dioxins in the soil in East Palestine. And the agency has since released a plan for soil sampling to be carried out by another Norfolk Southern contractor. But some are arguing that the EPA should do the testing itself — and should have done it much earlier.

Results Used to Deny Relief

The results of CTEH’s tests in East Palestine were used at one point to deny a family’s reimbursement for hotel and relocation costs. Zsuzsa Gyenes, who lives about a mile from the derailment site, said she began to feel ill a few hours after the accident. “It felt like my brain was smacking into my skull. I got very disoriented, nauseous. And my skin started tingling,” she said. Her 9-year-old son also became sick. “He was projectile puking and shaking violently,” said Gyenes, who was especially concerned about his breathing because he has been hospitalized several times for asthma. “He was gasping for air.”

Gyenes, her partner and son left for a hotel. At first, Norfolk Southern reimbursed the family for the stay, food and other expenses. The company even covered the cost of a remote-controlled car that Gyenes bought to cheer up her son, who was devastated because he was unable to attend school and missed the Valentine’s Day party.

But the reimbursements stopped after Gyenes got her air tested by CTEH. Gyenes was handed a piece of paper with a CTEH logo showing that the company did not detect any VOCs.

The next time Gyenes brought her receipts to the emergency assistance center, she said she was told that no expenses incurred after her air had been tested would be reimbursed because the air was safe.

A post office clerk, Gyenes described her financial situation as “bleeding out.” Nevertheless, she continued to foot the hotel bill. “I still feel sick every time I go back into town,” she said.

When she called the hotline, she got upset when she said a CTEH toxicologist told her that there was no way her headache, chest pain, tingling or nausea could be related to the derailment.

ProPublica asked Norfolk Southern about Gyenes’ situation. A spokesperson said the company reimbursed her $5,000, including some lodging and food expenses, after the initial air tests even though the company said her home is outside the evacuation zone. It noted that Gyenes used “abusive language” when questioning the toxicologist. (Gyenes acknowledged that she called her a “liar.”)

Norfolk Southern said it is working with local and federal authorities to arrange another test of the air in her home. “We’ll continue to work with every affected community member toward being comfortable back in their homes, including this resident,” a Norfolk Southern spokesperson said in an email.

After ProPublica asked about the family, Norfolk Southern restarted payments.

On Wednesday, when Gyenes returned to the emergency assistance center, she said that she was given $1,000 on a prepaid card to cover lodging, food and gas.

Sharon Lerner covers health and the environment. Previously, as an investigative reporter at The Intercept, she focused on failures of the environmental regulatory process as well as biosafety and pandemic profiteering.

Kirsten Berg contributed research.