Most Americans know St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital through television advertisements featuring Hollywood celebrities asking for contributions or the millions of fundraising appeals that regularly arrive in mailboxes across the country.

But a select group of potential donors is targeted in a more intimate way. Representatives of the hospital’s fundraising arm visit their homes; dine with them at local restaurants; send them personal notes and birthday cards; and schedule them for “love calls.”

What makes these potential donors so special? They told St. Jude they were considering leaving the hospital a substantial amount in their wills. Once the suggestion was made, specialized fundraisers set a singular goal: build relationships with the donors to make sure the money flows to the hospital after their deaths.

The intense cultivation of these donors is part of a strategy that has helped St. Jude establish what may be the most successful charitable bequest program in the country. In the most recent five-year period of reported financial results, bequests constituted $1.5 billion, or 20%, of the $7.5 billion St. Jude raised in those years. That amount, both in terms of dollars and as a percentage of fundraising, far outpaces that raised by other leading children’s hospitals and charities generally.

While a financial boon to St. Jude, the hospital’s pursuit has led to fraught disputes with donors’ family members and allegations that it goes too far in its quest for bequests.

St. Jude is a major research center with a 73-bed hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, that primarily treats kids from the Mid-South. Its bequest operation has a broad reach, with fundraisers based across the nation and a willingness to challenge families in court over the assets their loved ones leave behind. These battles can sometimes be lengthy and costly, spending donor money on litigation and diminishing inheritances. Family attorneys who specialize in such fights say that St. Jude can be especially aggressive, often pursuing cases all the way to state supreme courts.

“Think of all the fees for lawyers that didn’t go to St. Jude, not one child, not one cancer patient. Where is the sanity in all this?” — Vance Lanier, of Lafayette, Louisiana, who won a yearslong legal battle with St. Jude over his father’s estate but not before both sides spent heavily on the case

“At the end of it, there is very little to hold on to feel good about,” said Vance Lanier, of Lafayette, Louisiana, who won a yearslong legal battle with St. Jude over his father’s estate but not before both sides spent heavily on the case.

“Think of all the fees for lawyers that didn’t go to St. Jude, not one child, not one cancer patient,” Lanier said. “Where is the sanity in all this?”

The nonprofit even courts those who aid in estate planning and drawing up wills, sponsoring conferences where attorneys, financial advisers and estate professionals gather. On at least one occasion it offered attendees a chance to win a golf trip.

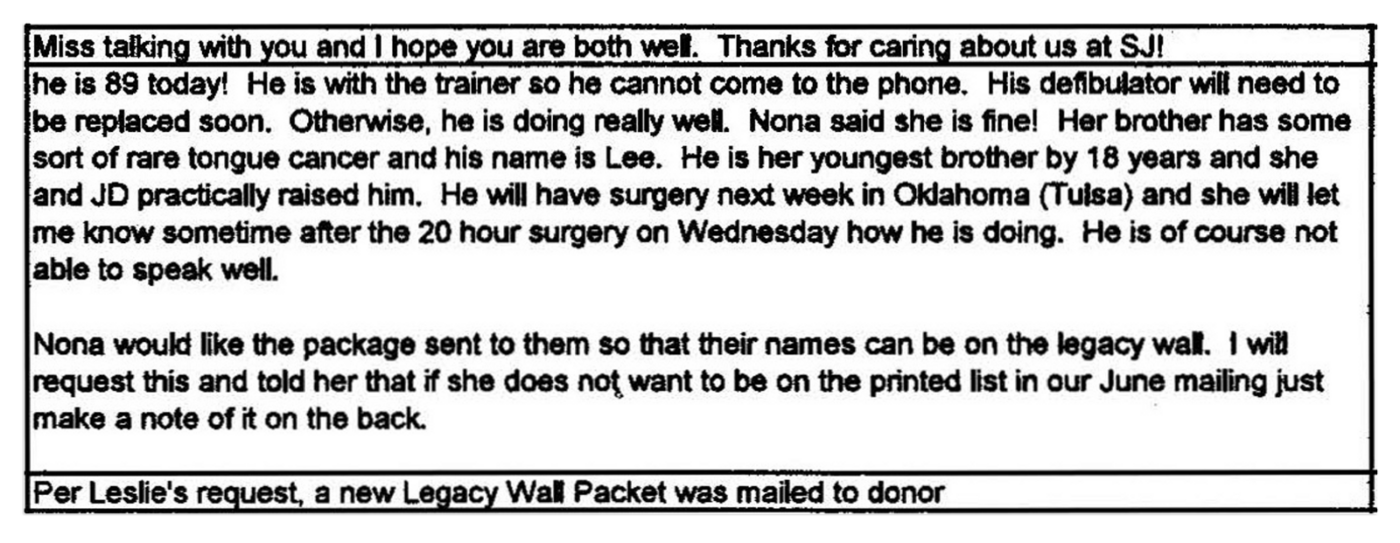

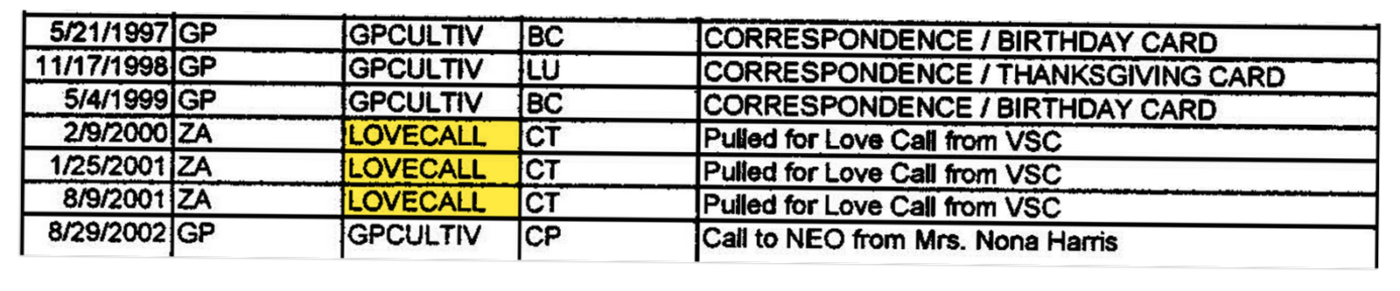

The prospective donors wooed by St. Jude are often people like Nona Harris: elderly, childless women with substantial wealth. Harris notified the charity in 1996 that she was considering leaving it a bequest. St. Jude spent the next two decades cultivating Harris. An internal database, built to collect information on donors, tracked nearly 100 calls and other contacts between Harris and the charity’s fundraisers during that time — an average of almost once every two months. It also noted information Harris shared with fundraisers.

By the time she died in 2015, the charity knew just about everything there was to know about her. It knew about the health problems of her husband, J.D., from the medicines that he took to the heart defibrillator that needed to be replaced. St. Jude knew that J.D.’s mother died when he was 13 and that one of Nona’s relatives had a rare tongue cancer. It knew the couple owned a condominium in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and a ranch with cattle and horses in Kansas.

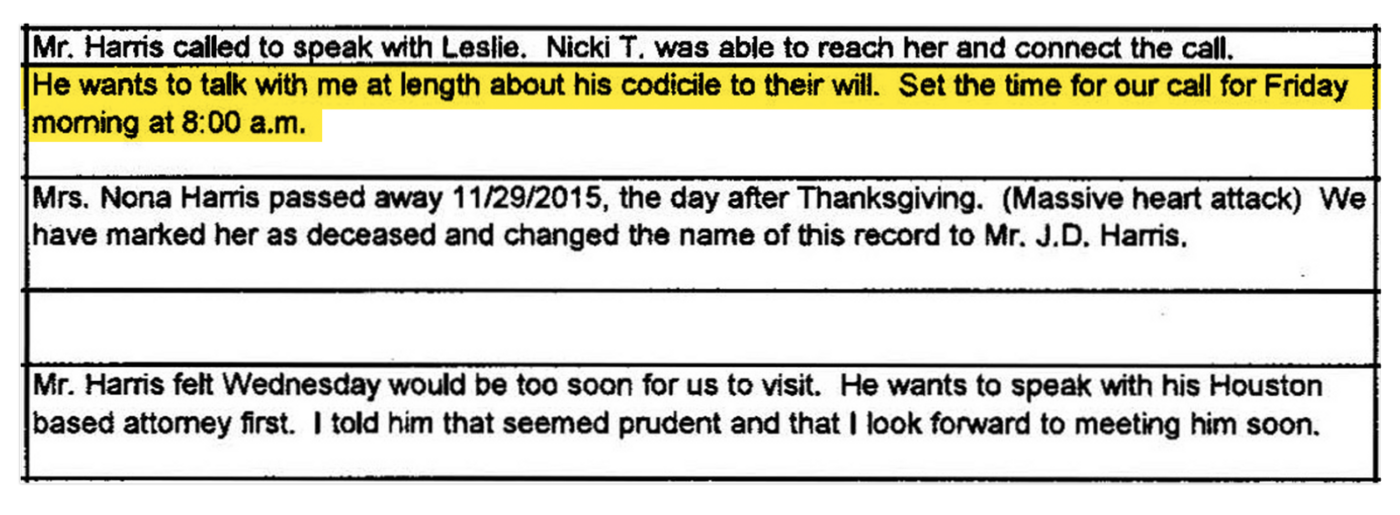

Most importantly, the charity knew the couple planned to leave their nearly $6 million estate to St. Jude. But Nona died before J.D., and after he changed his estate plan — reducing St. Jude’s payout by about $2.5 million — the charity went to court, triggering an expensive, drawn-out legal battle that pitted the hospital against several of J.D.’s family members.

Estate matters can be contentious, and many nonprofit organizations, including ProPublica, seek donations in people’s wills.

But St. Jude’s pursuit of such donations stands out. Bequests to St. Jude, as a percentage of total contributions, are more than double the national average of 9% as calculated by Giving USA.

And it receives more than other children’s hospitals that list bequest donations. Boston Children’s Hospital reported that estate and trust donations ranged from 3% to 6.5% annually during the three-year period of 2014 through 2016. Donations from estates to Children’s Hospital Colorado Foundation represents 3.5% of total giving at that hospital, according to its website. Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, said its bequest giving was aligned with national benchmarks such as the 9% figure from Giving USA.

For such organizations, any decision about waging legal fights with family members often comes down to a public relations decision.

“A legal fight could mar the reputation of a charity,” said Elizabeth Carter, a law professor at Louisiana State University who specializes in estate planning. “A lot of charities decide it is just not worth it; we don’t need that bad press. Occasionally you will see them fighting it, but not often because of the bad PR that comes from it.”

In a statement issued through its fundraising arm, the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities, or ALSAC, St. Jude said its bequest program “operates with the highest ethical standards and with bequest program best practices like other large charities.”

But it declined to answer specific questions about its bequest program, including how many cases are in litigation, or to respond in detail to questions about individual cases in which it has contested wills.

In 2017, Fred Jones, the ALSAC lawyer who oversees bequest matters, told an Oklahoma court that the charity was involved in more than 100 legal fights over disputed estates. Jones said many of those involved other parties challenging an estate in which St. Jude had an interest, but that it did pursue legal action on its own in some cases. Jones said St. Jude received about 2,000 new bequests in the fiscal year ending June 30, 2017. In a statement, ALSAC said it litigates less than less than 1% of the thousands of estate donations that it receives.

Jones told the court that neither St. Jude nor ALSAC “is in the business of trying cases,” in part because such efforts are funded with donations for the treatment of sick children. As a result, Jones said, St. Jude only initiates cases in which due diligence reveals substantial evidence to support a claim. “In effect, we’re using donor dollars — which we very carefully protect — in those cases where we believe that there has been a curtailment of the donor’s actual intent,” he said. Jones did not respond to a request for comment. St. Jude declined to provide further details on the use of donor funds to pay legal costs. In some jurisdictions, courts allow winning parties in a case to seek legal fees from the losing side and legal costs are sometimes reimbursed as part of settlement agreements.

To make the case that estate proceeds should go to St. Jude, the charity sometimes argues that relatives are not entitled to any proceeds from their family’s estates.

“Where I think the line is crossed is when they promote the disinheritance of children or families,” said Cary Colt Payne, a Las Vegas attorney representing a son who is battling St. Jude over his father’s estate.

In its statement, ALSAC said ProPublica’s reporting on bequests was “highly selective and flawed as it focused on a small handful of contested cases over several years out of the many types of these donations received each year. These contested estate matters often cover complex and sensitive family matters, include multiple charities, and involve local lawyers advising ALSAC/St. Jude.”

St. Jude’s responsibility, according to the statement, is “to carry out the clear written intent of a donor, typically stated in a written will or trust drafted by an independent lawyer, most often witnessed and notarized. These are beautiful legacy gifts with enduring impact, enabling us to remain focused on our mission: Finding cures. Saving children.”

“Love Calls”

St. Jude, founded by the entertainer Danny Thomas, makes a unique promise as part of its fundraising: “Families never receive a bill from St. Jude for treatment, travel, housing or food — because all a family should worry about is helping their child live.”

That pledge, and the ubiquitous appeals for donations that accompany it, has helped St. Jude become the country’s largest health care charity. Recent years have seen record-breaking fundraising gains. The hospital raises so much money that between 2016 and 2020, it annually steered an average of $400 million into a growing reserve fund that totaled $5.2 billion as of June 30, 2020 — the most recent figures publicly available.

To raise money, St. Jude depends on the related nonprofit ALSAC, which conducts the hospital’s fundraising and awareness campaigns.

ALSAC’s interactions with Nona Harris provide a window into the techniques used by the charity to encourage bequests and cultivate those who express an interest in making them.

In January 1996, Nona called St. Jude to let the hospital know she was considering making a large bequest, which at that time she said could be up to $500,000.

Phone calls from potential donors like Harris are just one of the ways ALSAC learns of potential bequests. Other times, the hospital is alerted by a financial planner or estate lawyer of plans by clients to leave money to St. Jude. Most times, proceeds from bequests just show up with no prior notice after a person has died. The charity also solicits them in fundraising materials, encouraging anyone open to considering St. Jude in their will to notify it using an enclosed information card and envelope.

Harris, after notifying St. Jude of the potential bequest, then asked that no one contact her. That request was apparently ignored as an ALSAC staffer was tasked with getting in touch with Nona a few months after her call, according to a printout of a computerized log of interactions with Nona filed in court.

ALSAC bequest specialists maintain a “portfolio” of estate donors who are ranked by importance, according to current and former ALSAC employees. The size and range of the ALSAC bequest operation gives it the advantage of being able to meet in person with donors anywhere in the country.

ALSAC sent Nona handwritten birthday and holiday cards, and in one case, just a note to say, “I thought of you today.” The cards were often followed by phone calls around the holidays to check in with her.

On four occasions — in 2000, twice in 2001 and in 2005 — Nona was listed for what were described in the log as “love calls.” St. Jude declined to provide details on what such calls entailed.

The ALSAC staff invited the Harrises to special events, including a 50th anniversary gala party in Los Angeles, as well as asking them repeatedly to come to Memphis and visit the hospital. “I will be sure to be at the front door waiting for your arrival,” a staffer wrote in 2007. Family members do not believe the Harrises ever visited.

One hint in the notes of why Nona chose St. Jude as a beneficiary of her estate was a comment she made in 2004 that she “was thrilled to do it since St. Jude is her patron saint.” Although the hospital is named after the saint, it does not have any religious affiliations. J.D. also had a fondness for the children’s hospital, according to family members, and would occasionally wear a St. Jude baseball cap sent to the couple by fundraisers.

The Harrises were different from other large bequest donors in one significant way. It doesn’t appear anyone from ALSAC ever visited them at their home.

Former ALSAC employees who worked on bequests said they would visit some donors dozens of times. They said some of those were older donors who were lonely and enjoyed the companionship. Internally, the jobs came to be known as “the tea and cookie positions” since that’s what many visits to donors involved. One staffer said he became so close to one donor that he attended holiday dinners at the family’s home.

An ALSAC employee based in Rhode Island said she would meet in person with 150 to 200 people a year throughout New England and upstate New York who indicated they planned to leave money to St. Jude or were considering it, according to testimony she gave in 2015 in a New Hampshire estate dispute.

The employee, Maureen Mallon, was an estate lawyer in private practice for 20 years before joining ALSAC as a philanthropic adviser in 2010.

“Part of my role is to connect them, to build a relationship with them, to give them more information about the hospital,” she said of visiting potential donors.

Mallon testified about her relationship with one donor, whom she visited at her home in person five times, usually for an hour or more. The woman — who was elderly, widowed and did not have children — would have lunch ready for the two of them and always sent Mallon home with baked goods. One time she called to make sure Mallon made it home safely. Mallon said the woman discussed details of her estate and shared family histories and relationships. She confided that certain relatives would be unhappy if they learned she planned to leave her home to the Memphis hospital. The visits and notes about what was discussed were recorded in a database, according to the testimony. Attempts to contact Mallon were unsuccessful.

The Harrises were private people who had retired to their ranch in Kansas following years of traveling the world as part of J.D.’s work in the oil industry. They used their Tulsa condo when they came for medical care in the city.

On the ranch, J.D. would rise early each day to drive the foreman around the 320-acre property to feed the scores of cattle and horses. He typically dressed in blue jeans, black cowboy boots with his initials on them, a cowboy hat and a white oxford shirt with two pockets that he used to carry a small notebook, a pencil and his checkbook.

J.D. was plainspoken and frank, friends recalled, while Nona was described as a generous person who was always impeccably dressed.

After Nona died on the day after Thanksgiving in 2015, J.D. became closer with his remaining family members, including two nieces and a nephew, according to court testimony.

J.D. was particularly fond of his great-nephew Brent Neitzke, who lived in Indiana and visited him at the ranch on a regular basis after Nona’s death. Most Sunday nights, J.D. and Neitzke would talk for hours on the phone. Neitzke said they discussed politicians, happenings in the world and J.D.’s travels. He said J.D. also talked about his estate and his plans to split it.

J.D. told his accountant that the estate plan he formed after Nona’s death was something of a compromise. He would still be honoring Nona’s wish to help St. Jude while at the same time taking care of his family.

When J.D. called ALSAC two months after Nona died to share the news that his wife had passed away, he told the staffer who was the main contact for Nona that he wanted “to talk to me at length about his codicile (sic) to their will,” according to court records. A codicil modifies or revokes parts of a will.

Later, the ALSAC staffer tried to set up a meeting with J.D. at his home, but J.D. said that it was too soon for a visit and that he wanted to speak to his attorney first, according to notes of the conversation recorded by ALSAC.

For ALSAC, the next step was the courtroom.

Court Battles

That’s where Vance Lanier found himself when St. Jude fought him over the distribution of his father’s estate.

Lanier is a financial planner in Lafayette, Louisiana, who helps clients with estate and trust matters. His father, Eugene, died in December 2015. His will directed that $100,000 from the proceeds of the sale of his home go to St. Jude.

But there was a problem. The elder Lanier did not own his home, according to his son. More than a decade earlier he had placed it in a trust, along with other assets, to benefit his three children.

To Lanier, it was a simple matter. St. Jude was not entitled to any money from the house sale. “He had given away his assets to put into a trust,” Lanier said. “My dad did not own it. He could have changed that while he was alive, but he didn’t.”

Still, recognizing that his father did want to make a donation to St. Jude, and hoping to avoid spending money on legal fees, Lanier said he offered St. Jude $25,000 to settle the matter. The offer was rejected, according to Lanier and his attorney, and St. Jude instead pursued the matter in a yearslong court fight. St. Jude argued that the elder Lanier, through his will, “clearly directed the sale” of the property and that $100,000 of the proceeds should go to the hospital.

A trial court ruled in favor of Vance Lanier. St. Jude appealed that ruling but eventually lost. The charity then asked the state Supreme Court to reverse that ruling, but the request was denied, ending the matter.

Lanier said the legal dispute was expensive for both sides. He spent $50,000 in lawyer fees. Even if St. Jude had won the case, he said, much of the money it would have received from the elder Lanier’s estate would have been wiped out by legal costs. St. Jude did not respond to questions about how much it paid its lawyers.

Lanier said he wrote to the chief executive of St. Jude complaining that the legal fight was a waste of time and the charity’s resources.

Before the estate dispute, Lanier said he and other members of his extended family were supporters of St. Jude and had collectively donated thousands of dollars to the Memphis hospital. That is no longer the case, he said.

“After this and seeing the waste, I don’t want anything to do with them,” he said.

Influence and Attorneys

One sign of the significance of bequests to St. Jude is that it frequently underwrites conferences for estate lawyers and financial planners, who can help clients determine which charities to leave money to in their wills.

In some cases, it is the only charity involved. Typical sponsors are mostly banks, trust companies and consultancies.

St. Jude has been a top-level diamond sponsor for the past several years of the Heckerling Institute on Estate Planning, an annual conference that typically draws more than 3,000 attendees.

The $30,000 cost of a diamond sponsorship allows St. Jude to bring as many as 10 employees to work at its deluxe suite on the exhibit hall floor. St. Jude also gets a list of all attendees and their emails and expanded networking times with conferencegoers.

At the 2017 conference, St. Jude raffled off a free trip to attend a PGA Tour golf event in Memphis.

The winner, estate and tax adviser Jack Meola, of New Jersey, said that in addition to attending the golf event, he and his wife were taken on a tour of St. Jude. “It’s a very emotional experience,” he said.

At the Heckerling conference the next year, ALSAC asked him to give a luncheon talk to attendees about St. Jude, Meola said.

He said he shares his experience of visiting the hospital with his clients when they are considering charities as beneficiaries.

“I always talk to clients and give them the example,” Meola said. “They may not end up choosing St. Jude, but I give them the emotional side.”

St. Jude’s relationship with a Las Vegas estate lawyer ensured it learned about a lucrative estate case in time to fight for the bequest all the way to the state Supreme Court, and it raised ethical questions about whether the lawyer had been fully transparent with her client.

The lawyer, Kristin Tyler, drafted a will in October 2012 for Theodore Scheide Jr. that directed his estate go to St. Jude. But after Scheide died in 2014, the original of that will could not be located. A guardian who served as the administrator of Scheide’s estate concluded that he destroyed it, rendering it null and void, and determined his money should go to his son.

In 2016, just as a court was on the verge of finalizing the passing of Scheide’s $2.6 million estate to his son, Tyler learned of the plans for the money and alerted Jones, the ALSAC attorney. Tyler knew to call Jones because in addition to Scheide she had another client: St. Jude.

A district court judge, after a hearing, ruled that the estate should go to the son as there were not two independent witnesses who could vouch for the existence and substance of the missing original will. St. Jude appealed that decision to the state Supreme Court, which overturned the lower court in 2020 and ruled in favor of the charity. Appeals in the case continue.

Tyler was vague about what prompted her to look into the matter at the last minute, writing in one email at the time that “for some reason I recently thought about Theo Scheide.” She was certain, however, that the money should go to St. Jude and not Scheide’s son. The two were estranged and Tyler said Scheide was adamant about disinheriting his son.

After calling Jones, Tyler then contacted a partner at a prominent Las Vegas law firm that worked with the charity. In an email, she advised the partner that St. Jude would be reaching out to him and “you need to jump on this quick.” She offered to help, writing, “I want to make sure this estate goes 100% to St. Jude and not to Theo’s estranged son.” She wrote that it would be “a shame” for the money to go to the son.

Tyler later testified that she had represented the hospital in at least two, and perhaps three, estate matters. She testified that she was unsure if she was working for St. Jude at the same time she helped Scheide draft his will. In any event, she said that it wouldn’t have been necessary to tell Scheide about her work for St. Jude because the interests of the two parties were not opposed to each other — meaning there was no conflict of interest. St. Jude did not respond to questions about its relationship with Tyler.

Legal experts said the need to disclose the relationship with St. Jude would depend on the nature and extent of Tyler’s dealings with the charity. Tyler declined to comment.

A district court judge, after a hearing, ruled that the estate should go to the son as there were not two independent witnesses who could vouch for the existence and substance of the missing original will. St. Jude appealed that decision to the state Supreme Court, which overturned the lower court in 2020 and ruled in favor of the charity. Appeals in the case continue.

Key to the supreme court ruling were affidavits from Tyler and her assistant testifying to the legitimacy of the missing will, saying that they witnessed Scheide sign it and that, to their knowledge, he had not intentionally destroyed or revoked it.

For Scheide’s son, Chip, the most painful part of the legal fight with St. Jude was not potentially losing out on his father’s estate but the way he was characterized by the charity and years of uncertainty over the potential inheritance. In appealing the case to the state Supreme Court, St. Jude repeatedly referred to Chip as a “disinherited” son and claimed his father had “no interest” in contacting him. He called it “intentionally hurtful.”

Chip acknowledges an estrangement from his father but says it was not rooted in anger or a dispute. Instead, Chip said, it was the result of a decision his father made in the wake of his parents’ divorce to remarry and move from Pittsburgh to Florida when Chip was 11 or 12. After he moved away, Chip only saw his father a few times.

“He made a choice,” Chip said of his father and the distant relationship between the two. Still, he said, the two stayed in touch. They regularly exchanged holiday cards and just a year before he died, Theodore sent Chip a congratulatory card and a check when he married for a second time.

Chip was in Las Vegas about a year before his father died and tried to contact him, without success. Later he learned his father was in the hospital at that time.

Despite the contention of St. Jude that Theodore did not want to contact Chip, Diane Prosser, a case manager for the guardianship service that managed Theodore’s affairs, said in an interview with ProPublica that Theodore talked frequently about his son toward the end of his life.

“I know towards the end, he mentioned his son a lot,” Prosser said. “I remember saying, should we be looking for his son?” Prosser said she discussed the matter with her boss but doesn’t remember any effort by the guardianship service to find Chip before Theodore died on Aug. 17, 2014.

“He Knew Exactly What He Wanted to Do”

J.D. Harris was admitted to the hospital for a heart valve procedure on Dec. 15, 2016, a little over a year after his wife died. During the operation, his kidneys failed, according to court testimony. Doctors told J.D. that if he didn’t begin dialysis he would die within days. J.D., who was 92, told the doctors he wasn’t interested in the treatment.

By this point, J.D. had not yet made the changes to his estate that he talked about during the previous months. On Dec. 19, he called his longtime accountant, Dwight Kealiher, from the hospital and told him he wanted to rework his trust and will.

Attorney Jerry Zimmerman, a well-known Tulsa estate lawyer, met twice with J.D. at the hospital on Dec. 21. Zimmerman questioned J.D. to make sure he was competent, asking him personal questions and inquiring about his assets. He said in court testimony that J.D. was lucid and accurately recalled details of his estate and his existing trust.

Zimmerman said J.D. told him he wanted to change his estate plan to split it between St. Jude and four family members, including Neitzke. J.D. also wanted $100,000 to go to Jim Tibbets, the foreman of his ranch, whom he considered a friend, Zimmerman testified.

Zimmerman returned to the hospital the next day with the reworked estate documents, but J.D. said he wanted Kealiher to be there to review them and didn’t sign. A day later, on Dec. 23, Zimmerman came back with Kealiher, who had just been released from a different hospital.

J.D., however, was in no condition to sign, according to his medical records. A hospital notary said he was “laboring” and might be confused. A nurse, concerned that J.D. was too weak to sign and incoherent, eventually asked everyone to leave the room.

Tibbets slept in J.D.’s room that night and said that J.D. woke up several times asking about the estate documents and requesting that Zimmerman come to the hospital so he could sign them. Tibbets explained it was the middle of the night and that wasn’t possible, court records show.

The next day was Christmas Eve and Zimmerman was not available to come to the hospital, court records show. He gave the papers to be signed to Tibbets. Overnight, Tibbets said J.D. again woke up and asked about the estate documents as well as inquiring about the animals on his ranch.

“He was adamant about it,” Tibbets said in an interview of J.D.’s desire to finalize his estate plans. “His mind was still sharp right until he passed away.”

Tibbets said he put a piece of cardboard underneath the papers and that J.D. meticulously signed each letter of his name, understanding the importance of the moment. When he finished, he told Tibbets he was “glad” it was done. He died later on Christmas Day.

Six months later, St. Jude began the court fight seeking to overturn a district court finding that the restated trust was properly executed and requesting a new trial on the matter.

The hospital said that it didn’t receive proper notice of the nature of the district court hearing on J.D.’s estate and that it was unfairly denied a chance to introduce medical records showing that J.D. was often incoherent, comatose or otherwise incapable of decision-making at the times he was asked to sign the reworked estate plan. The charity did not contest that J.D. signed the documents.

“He talked to his lawyer. He talked to his accountant. He talked to his family. He talked to his ranch hand, who was family to him,” Tulsa District Court Judge Kurt G. Glassco said in a ruling, which found that J.D.’s reworked estate plan was valid. “And he knew exactly what he wanted to do.”

After Glassco denied St. Jude’s request for a new trial, the charity then appealed to the state Supreme Court, which delegated the matter to the Court of Civil Appeals.

As the case dragged on, J.D.’s nephew Doug Holmes, who was one of the family members named as a beneficiary in the restated trust, wrote a letter to the St. Jude board of directors.

“The continued unfounded litigation has caused significant pain to family members, as we repeatedly have to relive the final days of our dear uncle,” he wrote in December 2018. “With each of St. Jude’s legal filings, the attorney fees increase, sapping precious dollars that could go to St. Jude families.”

In December 2019, the appeals court upheld the lower court ruling. In 2020, more than three years after J.D.’s death, his family members finally received their shares of his nearly $6 million estate.

Neitzke said his family remains mystified as to why St. Jude challenged the distribution of J.D.’s trust. The charity was still being granted a generous, multimillion-dollar bequest and J.D. even told the charity to expect a change from what Nona had promised before she died, he said.

Neitzke said he had been a supporter of St. Jude, but the litigation had changed his view.

“I thought this was a waste of time and money,” he said. “I will never give them another dime.”