The dissolution of the Soviet Union is the first news story I remember.

I didn’t know exactly what it meant at the time. I knew it was something major. Adults were worried. I remember mom being on the phone, talking in an agitated voice; neighbors and family in the kitchen discussing how there were tanks in the streets of Moscow, repeating names and words that made no sense to me at age 5: Boris Yeltsin. Putsch. Mikhail Gorbachev.

On the Soviet TV set, in what we thought was still the Soviet Republic of Kazakhstan, the main channel was broadcasting a ballet performance of Swan Lake. The USSR had started to crumble, but a Soviet person living there wouldn’t know about it from TV.

There were many news stories and historic events before that time, in which Soviet people were the protagonists but we and others were not fully aware of it. In the absence of free press, they formed their realities based on what other people said, what they heard from censored news and what they saw.

They lived in an alternative reality believing that everything is under control and their leaders wouldn’t fail them.

The world has changed in 30 years since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. But very little has changed with regard to how Russia treats the truth. In Russia, truth has always had a target on its back.

The story of the free press is the story of an impossible struggle; during the war in Ukraine, it has reached what seems like a new low.

In the Russian mainstream media, there is no war but a special military operation. No aggression but an effort to “demilitarize and de-nazify” Ukraine. There have been no civilian casualties, just actors and “fake news.”

In Russia, truth has always had a target on its back.

But there is a lot of criticism for the Western media and its lack of journalistic standards, for unfairly treating Russia and not covering stories that expose “atrocities” committed by the Ukrainian forces, such as the murder of the mayor of the town of Luhansk. Most of the articles in Russian media claimed there were no Western journalists in Mariupol, and that images from the Associated Press are staged, are not real.

The technique of whataboutism is a known tactic of Russian propaganda meant to shift attention to other things, to undermine trust in the enemy’s message, and to sow doubt.

A few days after the invasion, Russia passed a law eliminating journalists’ ability to report the truth about the war or to even call it “a war.” Violating the law could lead to up to 15 years in prison.

This measure has caused throttling of independent journalism even further. TV rain, Russia’s independent channel, had to temporarily stop broadcasting; it said the law makes it impossible for them to do their job.

The radio station Echo of Moscow was liquidated by its board. Recently, the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta, edited by Nobel-winning Dmitri Muratov, ceased publication until the end of the war. Six journalists of Novaya Gazeta have been murdered since 2000. The New York Times pulled its staff from Moscow. Bloomberg News, BBC, ABC and CNN International had to suspend broadcasting from Russia. Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter are all blocked (unless you have access to your own VPN). Access to TikTok has been limited.

I realize it’s hard for people in Europe or America to understand how people could believe it all. How could they not see or get it?

I also used to think that censorship and propaganda could not work at a time when people have access to many different sources. I was wrong. I saw it happening in the United States. President Donald Trump knew how to manipulate the American media by “flooding the zone.” He knew how to exploit false equivalence, both-sideism and ineptitude of some in the American press to cover and recognize authoritarianism.

Propaganda can be stronger than love when people are in the mode of survival.

President Putin does not have to design new tricks to bamboozle his people. He throttles the free press the way the Communists did. He stages massive rallies to show how the people support him, doubles down on loyalty, and exploits nationalistic fears and history myths.

It’s hard for me to believe that to justify the war in Ukraine, Russian talk shows and intellectuals talk about Stepan Bandera, the Ukrainian nationalist who was assassinated in 1959, and show images of genocide the Nazi Germany commited in the USSR somehow suggesting that that’s what Ukrainians are doing now. But it works. It makes people believe that they are being attacked, the way their loved ones were attacked in World War II.

Propaganda can be stronger than love when people are in survival mode.

To many Russians, believing Putin is a survival tactic. Showing courage and joining protests is costly. The image of Putin as a protector, liberator and a strong leader remains appealing.

For years, the narrative has been that Russia and the Russians were being attacked, their language was being canceled, their culture erased. It’s easy to sell the war to people under attack.

Someone besides Putin understood it well. Herman Goering, a high-ranking Nazi and Adolf Hitler’s right- hand man who said in 1946:

“Naturally, the common people don’t want war; neither in Russia nor in England nor in America, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy or a fascist dictatorship or a parliament or a Communist dictatorship… Voice or no voice, the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country.”

To many Russians, believing Putin is a tactic of survival.

Remember the U.S. invasion of Iraq?

On Russian television these days, it is the West trying to destroy Russia. But the Russian people – as Putin says himself – are able to distinguish a true patriot from “scum” and “traitors” and the Russian society will be able to purify itself.

It is a powerful and far-reaching message. In Russia and the Russian-speaking world in the former Soviet Union, a lot of people still get their news from television, including my family in Kazakhstan and relatives in the Donbas region in Ukraine. The selection of channels is limited and most people watch government-controlled Channel One.

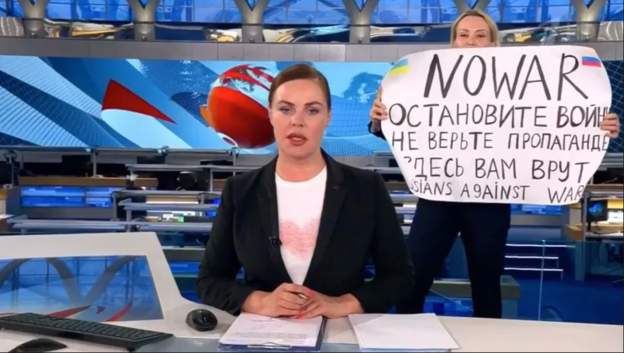

That’s why Marina Ovsyannikova is the face of courage and the struggle to get the truth out in Russia. She, an employee of Channel One, walked out with a poster, during a live news segment. Her poster read:

“No war

Stop the war.

Don’t believe the propaganda.

Here, they are lying to you.

Russians against war.”

Ovsyannikova was detained and fined. She was later released but now there is a criminal case pending against her. Channel One had to report on the incident with the poster blurred out in segments about the incident so as to not violate the new censorship law. France offered her asylum, but she made a decision to stay in Russia. For the West, she is a hero, for Russia, she is a traitor.

A popular Russian proverb says, “Trust but verify” (Доверяй, но проверяй) sounds especially ironic these days.

But if there is no way to verify, no free press to rely on, isn’t it only human to trust what is familiar, even if it’s not always accurate, especially in times of war?