Series: Under the Gun: How Gun Violence Is Impacting the Nation

As America emerged from the pandemic, communities continued to experience a rising tide of gun violence. School shootings and the rate of children and teens killed by gunfire both reached all-time highs since at least 1999. ProPublica’s coverage of gun violence reveals how first responders, policymakers and those directly affected are coping with the bloodshed.

Reporting Highlights

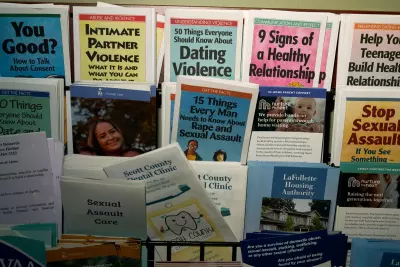

- Deadly Consequences: Tennessee consistently has one of the highest rates of women killed by men, and most of those homicides are committed with a gun.

- Unique Barriers: Victims in rural areas have access to fewer resources, while misconceptions about domestic violence and attitudes about guns can make it harder to disarm abusers.

- Unlikely Leader: One county on the Kentucky border has emerged as a model for how to keep domestic violence cases from escalating.

These highlights were written by the reporters and editors who worked on this story.

Before rural Scott County remade itself into a model for managing domestic violence, Jade Peters didn’t know where to turn for help. Her ex-boyfriend was stalking her and threatened to kill other men who talked to her.

She knew he had a gun, but so did many people in Scott County, and she didn’t think the justice system would take her seriously.

One night in 2009, Peters was walking up her steps when she saw someone approaching. As he got closer, she realized it was her ex-boyfriend. She fumbled with her keys, trying to set off her car alarm.

He pulled his hand out of his pocket. A sudden bright light pierced the darkness — the flash of a gun firing.

The bullet tore through Peters’ mouth and throat, with fragments lodging in her spine. When she was able to drag herself into her house to call for help, she remembers avoiding her reflection in the mirror, not wanting to see what damage the bullet had done.

A few years ago, Scott County decided that the system that Peters and other domestic violence victims across the state contended with wasn’t good enough. Tennessee consistently has one of the highest rates of women killed by men, and most of those homicides are committed with a gun. Yet, over the years, the state has loosened its gun laws, making it easier for people to buy and carry firearms. While the state bars domestic abusers and people with felony convictions from having guns, WPLN and ProPublica found that those laws are rarely enforced.

Tucked into the Appalachian foothills along the Kentucky border, Scott County recognized that victims in rural areas face unique barriers. There are few resources, like domestic violence shelters. Law enforcement and the courts typically lack staff and training. And cultural attitudes about domestic violence and guns can make officers and judges less likely to believe women or more reluctant to take firearms away from abusers.

The county completely overhauled the way it handles domestic violence cases. It brought most of the agencies that deal with domestic violence into one building called the Family Justice Center. It then started one of the state’s only court programs solely dedicated to handling domestic violence cases.

And vitally, the county took steps to better ensure that people subject to domestic violence charges or protection orders don’t have guns.

Peters said that if the reforms had existed when she needed them, she would have known where to get help. “It would have made a difference,” she said.

Separating dangerous people from their guns is an issue that much of the country grapples with. But in Tennessee, “it’s even more inconsistent in these rural communities,” said Heather Herrmann, who oversees a statewide group that studies domestic violence homicides. She said in rural areas, judges are more likely to consider things like whether accused abusers hunt or have jobs that require guns.

In rural Lewis County in Middle Tennessee, for example, Judge Mike Hinson said protecting gun rights weighs heavily in his decisions. It can be hard to justify signing an order of protection — which can bar someone from coming near the victim, contacting them or having firearms — if a gun wasn’t involved in the domestic violence incident, he said.

“It’s those close cases where I try to balance a person’s rights — because they do have a Second Amendment right, and they do have a right to protect themselves, and they do have a right to get a job,” Hinson said. “That’s the tougher balance.”

It’s a balance he acknowledged he doesn’t always get right.

Even if a judge orders someone to give up their guns, there’s a glaring gap in Tennessee’s system. It’s one of about a dozen states that allow someone to give their gun to a third party like a friend or relative instead of a law enforcement agency or a licensed firearms dealer. And it doesn’t require that the person be identified to the court. In such cases, someone could say they gave up their guns but still have access to them, advocates for domestic violence victims say.

Scott County saw that gap and decided to change its firearms form, requiring abusers to name the person who is holding their guns and list their address. That person has to sign to verify they have the guns. Scott is the only one of Tennessee’s 95 counties that has done this, victim advocates say. They have asked the Tennessee Administrative Office of the Courts to change the form statewide, but the office says the legislature would have to do that.

It’s difficult to measure Scott County’s success because the numbers are so small. But data from the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation shows that while domestic violence incidents have fallen slightly across the state, in Scott County, they’ve dropped by more than half, from nearly 250 in 2009 to an average of less than 100 in recent years. Victims are seeking protection orders from the courts more than they did before the reforms — a sign that there’s more trust in the system, victim advocates say. And far more requests are being approved.

“Some People, It Was Just a Bad Day”

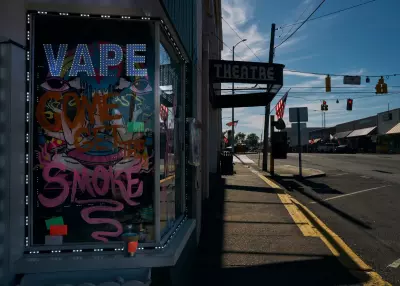

No other rural county in Tennessee has yet followed Scott’s lead. And throughout the state, old attitudes prevail. On the other side of Nashville from Scott County is a region of rolling hills and cropland where guns and hunting are also a big part of life.

This area of Middle Tennessee is represented in Congress by Rep. Andy Ogles, a Republican who in 2021 sent out a Christmas card of his family holding guns. (Ogles didn’t respond to calls or emails from WPLN and ProPublica but has told reporters he didn’t regret the card.) Jason Aldean’s controversial music video, “Try That in a Small Town,” was filmed at a courthouse in the area and served as an anthem of old-school, small-town values that critics said was a racist rallying cry for vigilante justice and gun violence. (Aldean has defended the song and video.)

That culture permeates all the way up the justice system to judges, Herrmann said.

“When you have a really insular community, a really gun-focused community, and often a community that maybe has some misconceptions or stereotyping of what domestic violence is and what it means, then you have judges, not always, but often, who carry those same beliefs,” she said.

Judges in Tennessee have an incredible amount of power in how they run their courtrooms, which can greatly affect domestic violence cases. If a case lacks obvious physical signs of abuse, judges may fall back on their own notions about domestic violence, which research shows favors defendants.

Hinson said he sees himself as a representative for the culture of Lewis County. The county proudly boasts one of the largest collections of mounted trophy heads in North America. The old courthouse has a bullet hole from when a man going through a divorce brought a gun to confront his wife. The new courthouse is across the street from a store advertising that “we sell ammo.” With only about 12,500 residents, the county is the type of place where most people know each other, which can make domestic violence cases difficult.

Since 2014, many of those cases have gone before Hinson, a Lewis County native with icy blue eyes and gray hair.

Some folks around Lewis County call him “the people’s judge”: He often wears a quarter-zip sweater or a button-down shirt in court instead of a judicial robe. And he speaks plainly, like he’s talking to a friend he ran into at the store instead of someone in a jailhouse jumpsuit.

Hinson’s casual attitude and off-the-cuff remarks caused him to be suspended by the Administrative Office of the Courts’ Board of Judicial Conduct in 2021. In one case, in which he denied a woman an order of protection, the board said he made a “demeaning” comment, telling the couple that another judge would “wade through the bullshit” in their divorce. He later apologized for the remark.

Sometimes, Hinson said, he finds the law constricting and prefers to take his own approach. Once, that resulted in him dismissing hundreds of traffic tickets because he thought the community was being overly targeted. It made him popular among some residents — and less so with the Tennessee Highway Patrol.

“I don’t believe the law was made for us to worship,” Hinson said. “I believe the law is a tool.”

Photographed by Stacy Kranitz.

That applies to the domestic violence cases he sees in his courtroom, which, he said, often result from addiction. It’s a struggle Hinson himself relates to. He said he had a drinking problem and anger issues that ended his last marriage — something he shares with the men who appear before him in court.

“Some people just might need a little anger management,” Hinson said. “Some people, it was just a bad day and the only time it’s ever happened.”

Hinson also said he thinks some women overuse protection orders to gain the upper hand in a divorce case or custody battle.

“This is stuff that we hear from every corner of the state,” Herrmann said. “In these small towns in particular, people talk. They know what the judge has said to other people. They know how other people’s cases have gone.”

“I’m Gonna Take His Side”

Some victims who went through Lewis County court said Hinson’s sympathy for the men made them feel dismissed or like they were the ones being reprimanded. Multiple victims asked not to be named because it’s a small community and they worried it could affect their cases. WPLN and ProPublica also sat in on Hinson’s court.

In February, Hinson admonished a woman who sought a protection order against her ex-boyfriend after he fired a gun into the ceiling during an argument. Instead of granting the order of protection, Hinson put the man under a no-contact order, which didn’t require him to give up his firearms.

He told the man he couldn’t reach out to the woman, but he also told the woman her ex-boyfriend wouldn’t be held responsible if she contacted him first and he replied. If that happens, Hinson said, “I’m gonna take his side.” And he urged her not to do what some women do, reaching out to their partners after leaving court to work out their problems. “We’re not going to be doing that,” he told her.

A month later, another woman in Hinson’s court seemed surprised by the way the judge spoke to her estranged husband after he assaulted her. Instead of chastising him about his behavior, Hinson appeared to try to motivate her husband by telling him his wife thought he was “a great guy.”

The woman, sitting in the courtroom that day, leaned over to a victim’s advocate and said, “I never said that.”

Scott County’s New System

About 200 miles away, as the early morning fog cleared over the Scott County Justice Center in May, men slowly trickled into the courtroom under a sign in Greek that translates roughly to “a man’s character is his fate.” Their work boots thudded on the floor as they found seats on the wooden benches.

“All rise,” the bailiff said. “Domestic violence court is now in session.”

The men had already been convicted of domestic violence or were subject to protection orders. They were there so that Judge Scarlett Ellis could monitor whether they were keeping up with their probation appointments and other conditions like mental health and addiction treatment.

She looked up over her glasses with a kind smile at the group of men in front of her, the way a teacher might greet her class. Then one by one they stood in front of her. Ellis peppered them with questions: How has therapy been going? Have you avoided contact with your victim? What have you learned in batterers intervention class?

Ellis’ approach is encouraging but not lenient. When it’s clear that the men before her have made strides toward changing their behaviors, she doesn’t hesitate to tell them. One man stood at the podium, his hands clasped behind his back as he responded to her questions with, “Yes, ma’am,” and, “No, ma’am.” He had an interview later that day for a better-paying job, he told her.

“You’ve changed your life,” she told him. “I can see it. I really can.”

Ellis can use her discretion to have those who are doing well come to court less often. But if they’re not complying, she can also extend their probation or send them to jail.

Later in the day, when victims came to the domestic violence court for new cases to be heard, they were ushered by a court advocate into a back room to keep them separate from the men they say abused them. It’s one of many victim-centered changes the court has made. When their protection order hearing comes up, the victim stands at one podium, the offender at another, with the court advocate and a sheriff’s deputy between them.

Domestic violence court is held on a separate day from other cases to protect victims’ privacy.

“I was already embarrassed with what all had happened and being assaulted and then to have to be in a room with people who had done drugs and stole from others was just more embarrassing and belittling,” one person wrote in a community needs assessment that was conducted before the court was created.

Ultimately, a judge’s orders are only as strong as their enforcement, which Scott County has also tried to address. Like many rural counties, the Scott County Sheriff’s Department is small and understaffed. But it has a dedicated domestic violence officer to help victims.

“I’m their voice,” Deputy Danielle Gayheart said in a raspy twang. “They’ve done their side of it” by getting the order of protection, she said.

Photographed by Stacy Kranitz.

Gayheart has listened to jailhouse phone calls to see if an abuser was contacting a victim. She also checks social media. Once, a man posted a picture of himself hunting deer with a gun. When she sees those things, she’ll charge people with violating protection orders.

“When it comes to anything like that, I’m your girl,” she said.

“We Repeat What We Don’t Repair”

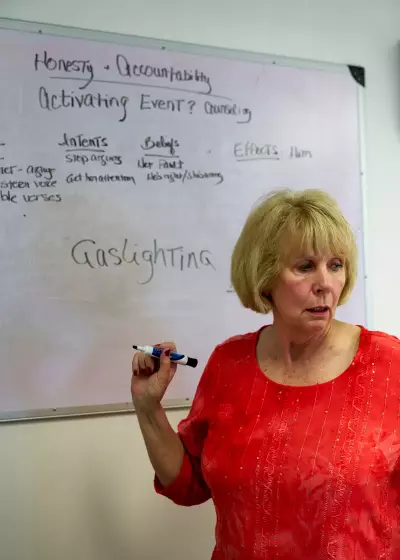

One of the keys to holding defendants accountable in Scott County is its batterers intervention program. In other rural counties, attending one can mean a long drive: In Lewis County, for example, the closest one is over an hour away. Judges in those places often won’t list it as a court condition because it’s too hard to get to. But Scott County’s class is 10 minutes from the courthouse.

During one class, six men crowded around folding tables pushed together in a square. “We repeat what we don’t repair” was scrawled on a white board on the wall.

The facilitator led them through an exercise on how to recognize the signs of anger in their bodies and stop it before they take it out on someone else. Feeling hot-headed? Try sticking your head in the freezer. Feeling restless? Take a walk. Clenching your teeth? Chew a piece of gum. Many of the men are still in the relationships that put them in court, so creating these plans is urgent.

While the 26-week class is court-ordered, the men weren’t shy about participating.

“I’m not real good at showing my feelings,” one man said. “I never have been. You know, I was raised —”

“You don’t wear your feelings on your sleeve,” another chimed in from across the table.

“That’s right,” the first man said. “Growing up, you know, I was raised that you’re a man. You’re not supposed to show that because nobody gives a shit. You’re supposed to be stronger than that.”

Photographed by Stacy Kranitz.

Programs like this one have led to change, according to Peters. After the shooting, her ex-boyfriend pleaded guilty to attempted murder and was sentenced to prison. Peters recovered from her wounds and went back to school to become a lawyer, representing clients in Ellis’ domestic violence court.

She said men in Scott County know that when they’re brought to court on a domestic violence charge, there will be serious consequences.

“Men are somewhat afraid of that,” Peters said. “They’re very aware that you can be dispossessed of firearms for a year, that you can lose a lot of your rights, that you can be sentenced to programs and court appearances.”

She said that empowerment for victims and accountability for offenders has had an impact beyond just the court program — the system change has led to broader cultural change in Scott County.

“There’s still women who are in bad situations,” Peters said. “It’s just that now there’s more help for them.”

Mariam Elba contributed research.