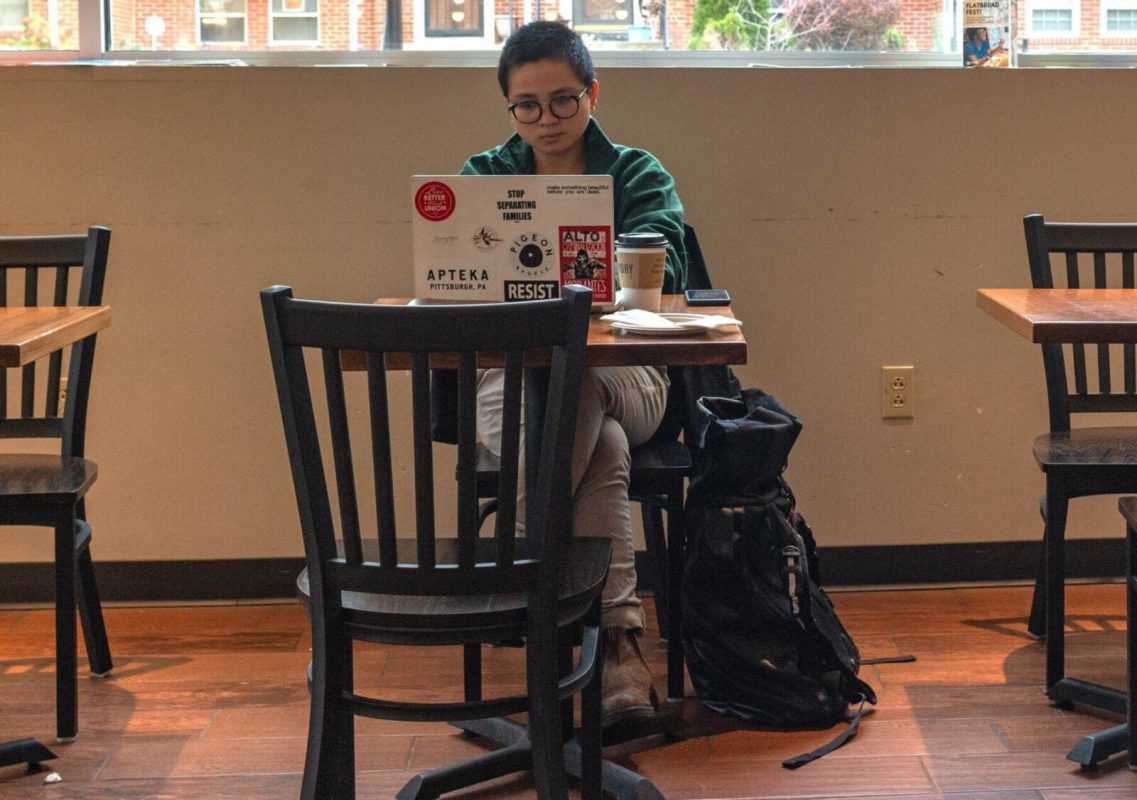

On a Tuesday afternoon at Everyday Cafe on North Homewood Avenue in Pittsburgh, two women meet for lunch and bring a puzzle to piece together while they catch up. Two tables over, a young man with headphones works quietly on his laptop. Nearby, two young professionals meet for a chat.

“I love coming here for that reason,” said Wasi Mohamed, Pittsburgh director for community entrepreneurship at Forward Cities. “Homewood needed this. There’s got to be a place that ties everyone together.”

Everyday Cafe, built in 2017 by the Oasis Project, a community and economic development effort by the Bible Center Church, puts profits from the cafe back into neighborhood-based causes and organizations. Mohamed, also a resident of Homewood, said that places like this are key to establishing inclusive growth for entrepreneurship in communities, which is the root of Forward Cities’ mission.

“We believe that within these postindustrial cities, main streets are an important part of the revitalization,” Mohamed said. “On main streets like Penn Avenue in East Liberty, we wish that, as it became a high-cost area, that community businesses were supported and they could benefit from that rising wave, but that rising wave sunk all those ships. Now you have macaroon and milkshake places, which are delicious, but they are not the flavor of the community.”

“We believe that within these postindustrial cities, main streets are an important part of the revitalization.”

The goal of Forward Cities is to ensure that something like that doesn’t happen again.

“North Homewood Avenue. used to be a thriving main street, and it completely died. Now they are trying to bring it back,” Mohamed said. “Can we do it right this time? That’s the hope.”

In January of this year, Mohamed joined Forward Cities, a national nonprofit working advancing equitable entrepreneurial ecosystems in local communities. Pittsburgh is one of 25 cities in the Forward Cities learning network and is in the middle of a two-year Community Entrepreneurship Accelerator initiative which includes launching pilot programs to increase support for local entrepreneurs in Pittsburgh neighborhoods, including Homewood.

Throughout the process, community organizations and entrepreneurs have been central to the design and implementation of the programs which are designed to be sustained well beyond the two-year Accelerator.

“The focus in on equity and ensuring that minority entrepreneurs and other entrepreneurs that are typically under-connected, underserved and under-resourced have a chance to sit at the table,” he said.

Before becoming Pittsburgh Director for Community Entrepreneurship at Forward Cities, he served as the executive director of the Islamic Center of Pittsburgh for four years.

“There aren’t that many Muslim jobs in the area, so I wanted to ensure that we had room for the next generation of leadership to grow,” he said. “I wanted to stay on the ground with people while working with foundations and nonprofits, and this job with Forward Cities allowed me to do that. Economic justice is a space that I am very passionate about… I wanted to contribute to making a more just economic system in the region and work towards economic inclusion.”

The program will take place in two zones, with the potential to scale and expand what works to other areas of the city in the near future. The east zone includes Homewood, Larimer, and Wilkinsburg, and the south zone includes Allentown, Knoxville and Mt. Oliver. Forward Cities worked with a broad array of cross-sector community leaders to choose these neighborhoods based on an analysis that determined what areas had an emerging entrepreneurial base and if they had existing community organizations to support the process.

Defining and Defying Barriers

As part of the initial stages of this program, Forward Cities sought out people and professionals within these communities to identify barriers that they face toward successful entrepreneurship. After a community survey, Forward Cities brought those individuals back into the process for idea sessions.

“We got them together and said, ‘here’s a barrier that the survey said. How do we address this?” Mohamed said. “One of them, for example, was awareness. People are not aware of existing support for entrepreneurs. How do you build out an ecosystem of entrepreneur resources when people don’t even know that they exist?”

After a brainstorming session, the groups narrowed down their ideas to four “MVS”s, Mohamed said, which stands for “minimal viable solutions.”

The first MVS is a community navigator—a case manager for entrepreneurs.

“One of the things we found was that there is an issue with cultural competence within entrepreneur-serving organizations. They aren’t understanding how to serve and market to minority communities, and there is lack of awareness of existing support,” Mohamed said.

The community navigator would be someone from the community who speaks the entrepreneur’s language and can explain the ecosystem of resources, while also helping them determine what resources to seek out based on the stage of their business.

“It’s hard to find your way into the right rooms,” Mohamed said, especially for those who already face so many barriers. “We are hoping that this navigator will be able to assist with that. It’s a simple solution that should make the ecosystem a little bit tighter.”

It’s important to note, Mohamed said, that community navigators are not new.

“Just people who are out there, giving their own time, helping business owners and aspiring business owners,” he said. “What we want to do is pay them, make sure they are supported and standardize the process.”

While the Forward Cities team is clear that this is what the community wants and that it is a good idea on paper, it still needs to see the effort at work.

“We are going to test it out, create the intake process and the training for navigators, get some people through the program and then see how it goes,” Mohamed said. “And if it goes well, we will expand, go into other communities and have more navigators.”

Part B of the navigator program includes “entrepreneurship hubs” that can serve as a meeting place in these target neighborhoods.

“We ideally want the navigators to meet people from the communities that they are in and not require people to go to the North Side if they are from the East End, for example,” Mohamed said. “Right now, we decided that the Homewood CEC is where one will be, and another one will be at Work Hard Pittsburgh in Allentown.”

To grow on the navigator option, Forward Cities is also trying to build an “Ecosystem Resource Platform,” which will serve as an online, one-stop-shop for entrepreneurial resources.

“It’s like the navigator, but online,” Mohamed said. “It will have a front end that you as an entrepreneur or aspiring entrepreneur can interface with and use to quickly find a resource.”

Not only will this become a directory of resources for communities, but it will also have a back-end that Forward Cities can use to track their case management. Navigators can use the system to track information on clients who come into the intake process and see where they are in the program.

Changing the Face of the Entrepreneur

Another way that Forward Cities plans to create a more inclusive economic ecosystem in Pittsburgh is by launching a campaign that challenges the idea of the “typical entrepreneur,” and tells more stories of successful minority businesses.

“When a lot of people say entrepreneur, they assume it is like a white dude in their twenties, working in a basement and doing tech stuff,” Mohamed said. “That’s the stereotype when in reality, that is not the majority.”

According to a report by the Federal Reserve, businesses owned by black women account for 59 percent of all black-owned businesses, which makes black women the only business owners with a higher business ownership share than their male counterparts. Another study by the National Immigration Forum showed that, as of 2015, immigrants have founded 51 percent of the country’s startup companies worth $1 billion or more.

Mohamed said that controlling the narrative about the types of people who are successful entrepreneurs can not only enhance the local perception of the city being inclusive and innovative, but it can also inspire other minorities to launch their own business.

“We want to highlight people who are doing phenomenal work, people of color who having amazing businesses,” he said.

The other part of the inclusion campaign will target entrepreneur-serving organizations and show them how to become more culturally competent and inclusive in the Pittsburgh ecosystem.

“We want them to see through an equity lens within their organizations,” Mohamed said.

“The problem with the growth that has come in is that it has exasperated the issues of income inequality and wealth inequality.”

An Inclusive Story for Pittsburgh

While Pittsburgh continues to acquire accolades including the second most livable city in the U.S., according to the 2019 report from Economic Intelligence Unit, and Glassdoor’s 2018 best city for jobs, two years in a row, there is still work to be done to become a more inclusive city.

A recent report led by the University of Pittsburgh researchers—“Pittsburgh’s Inequality Across Gender and Race,” showed that, compared to similar cities, black women in Pittsburgh face lower rates of employment and college readiness and higher rates of poverty and maternal mortality. It also found that black men face higher rates of homicides, occupational segregation, and disease.

“As of now, [Pittsburgh] is not a place where people of color feel like they see the rest of their lives here, regardless if their black or brown or an immigrant, this is a city that you stop in or are often trying to get out of,” Mohamed said.

“What can we do to reverse that? What can we do to make the story of the new Pittsburgh be one that is inclusive?”

The answer to that question, he said, “is how we retain our growth.”

Mohamed added that while Pittsburgh’s growth is exciting, is it important to not leave minorities behind in the process.

“The problem with the growth that has come in is that it has exasperated the issues of income inequality and wealth inequality. Inclusion hasn’t been a part of the vision of Pittsburgh,” Mohamed said. “It was just trying to survive. It was just trying to make sure that we clawed our way out of recessions and hard times, but it did not think of the people of color who stuck through it and stayed in Pittsburgh.”

And now, as Pittsburgh is moving into the renaissance, these disparities are coming to the forefront.

“Like East Liberty,” Mohamed said. “It became a ‘nicer’ area by removing certain people. That’s not the story we want for Pittsburgh. We believe that the people who want to work hard should be given the opportunities to do so, to start businesses and grow.”

Click here for a video featuring more about Forward Cities.