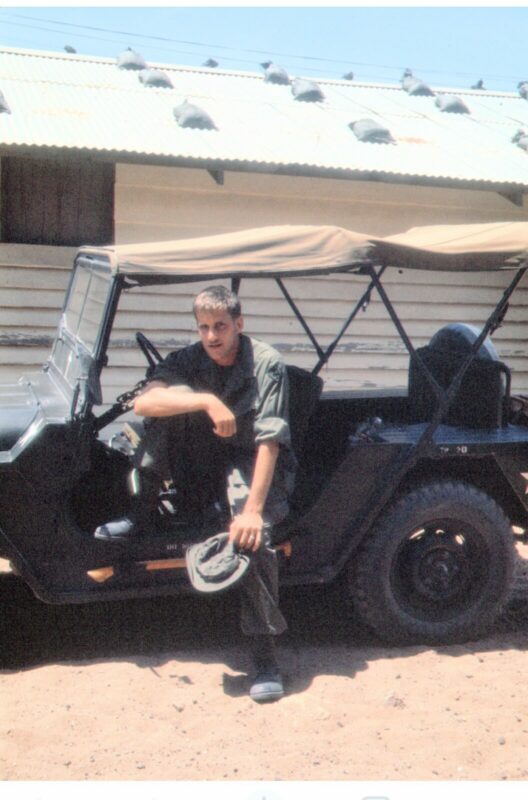

On a trip in 2019, a stranger took note of my Vietnam veterans’ hat.

“Thank you for your service. Do you ever get tired of hearing that?”

I flashed back to the climate of misunderstanding in the United States when I returned from Vietnam in 1970.

Smiling, I shook my head.

“Never.”

Nearly 50 years earlier, my wife Joanie and I spent five days in Honolulu, on my rest and relaxation break from the war. In a student bookstore, I was greeted with laughter because of my short military-cut hair.

A year later, I was dispatched from Arizona to San Francisco for a weekend conference and advised not to wear my uniform.

The war is over for me now, but it will always be there, the rest of my days

Back in civilian life in the Pittsburgh suburb of Freeport, an Armstrong County town of barely 2,000 along the Allegheny River, I used to hide my two Bronze Stars in my sock drawer in favor of displaying my completion medals from my four New York City marathons.

Not only didn’t I own a Vietnam hat, but I also would not have worn one at the time.

My transition into daily life at home was considerably more gentle than those of some fellow ‘Nam vets who shared their stories — not because I was a writer, but because I was one of them.

The clichés of that era were real for them: being called “baby killers,” being spat upon, being denied jobs because of the perceived baggage they brought back with them.

Vietnam was an undeclared war, with its own rules that often didn’t make sense, with its sad lies and hypocrisies. But we didn’t have to steal the soul, that spirit from some of the men and women who served there.

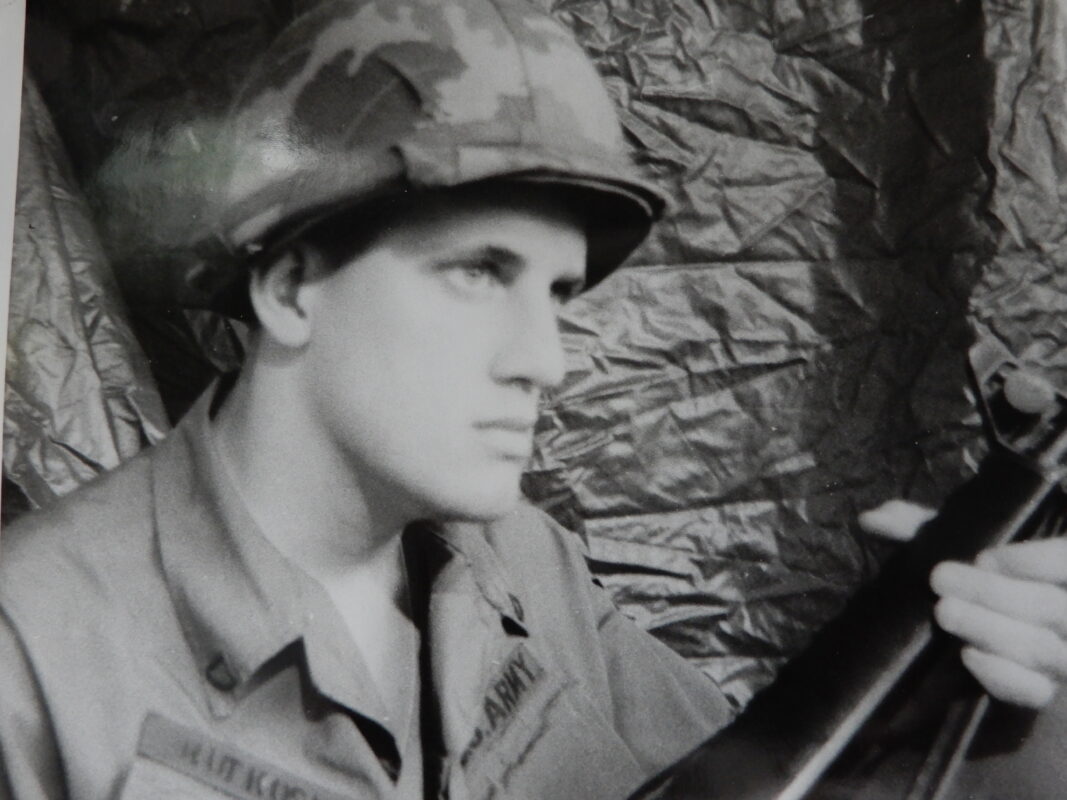

The warrior was often made to feel the war was his fault. But really, he was just the kid next door who went and did his duty.

What do you tell someone about war? How do you make something so personal understandable to someone else?

It’s not easy to make them feel the sand that you slept in, and sometimes, unavoidably, ate.

Nor is it easy to make them feel the results of the malaria pills you took each Monday that held your body prisoner for a day, and the loneliness and sometimes fear that gripped it for a year.

How do you tell people how some felt when, after a year in Vietnam, after missing some of the most important events in their lives, they stepped off that plane in the U.S. and into the darkened, ugly heart of an embarrassed nation?

What do you tell someone about the men and women you served with who are still hurting, still fighting Vietnam?

How do you explain to an employer, who asks you where you want to be in five years, that, with all due respect, you’re still struggling to find relevancy with that question?

Surviving Vietnam taught you to appreciate the right here, the right now, as a success.

And then we flash forward to the modern era of the desert wars and the new, welcome awareness that the men and women who go to war should not be criticized, but celebrated for what they have been asked to do for their country.

Many Vietnam vets are pleased that society, though decades late, seems to be trying to play ”catch up” for its initial oversight of their service, now making sure they are included in the modern wave of patriotism.

Restaurants offer discounted and, on Veterans Day, free meals. Schoolchildren fashion homemade cards. And sports teams, churches, and other organizations show their appreciation for service in a variety of ways throughout the year.

No longer are Vietnam War veterans swept under the rug of America’s consciousness.

Whether a result of the devastating reality check delivered in the terrorist attacks of 9/11, or just cultural change, many believe that society finally has gotten it right in its relationship with the men and women in the armed services.

Organizations such as the non-profit Vietnam Veterans of America are committed to keeping it that way. Its founding principle: “Never again will one generation of veterans abandon another.”

In this new era of understanding, I decided a couple of years ago that I want to live by the words of the character of Chris Taylor, portrayed by Charlie Sheen, in his soliloquy at the end of the Vietnam film “Platoon.”

“The war is over for me now, but it will always be there, the rest of my days … . But … those of us who did make it have an obligation to build again, to teach to others what we know, and to try with what’s left of our lives to find a goodness and a meaning to this life.”

The Bronze Stars have come out of my sock drawer. I bought a Vietnam veteran hat in Pittsburgh’s Strip District, which I wear every day to honor my hometown friend Dale who did not make it home from war.

That $10 hat has made connections almost everywhere I go. Strangers walking up to me in cities across the country and saying, “Thanks for your service.” Fellow ‘Nam vets coming forward to talk. Even a TSA agent acknowledging my service, escorting us to the head of the line at Denver International Airport.

Once, a flight attendant, noticing my hat, called attention over the public address system to the fact that there was a Vietnam veteran aboard. The passengers applauded.

I don’t seek recognition. But I do hope people remember and recognize those who didn’t come back, such as my friend Dale — and those who did and are still fighting that war in their heads