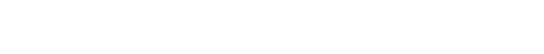

Many lament the “demise of American manufacturing.” However, as this Postindustrial columnist points out, manufacturing hasn’t disappeared in the United States, but it has “radically changed.”

If our politics were “normal” (meaning pre-Trump), the upcoming election would be decided on which candidate actually had a better plan to close the yawning economic divides between America’s thriving city regions – many on the Coasts- and hollowed-out heartlands—a chasm lamented by David Brooks in his recent New York Times column “Recipe for a Striving America.”

Wishing it so, I feel compelled to try and redirect the diagnosis of the thoughtful and well-intentioned Mr. Brooks around what ails our heartland’s economy, alienates its residents, and offers a better recipe for the heartland and, by extension, America’s revival.

I’ve lived and worked in Michigan for 35 years, grew up in West Virginia (both places hit hard by the economy’s restructuring from their glory days), and have made the spread of economic opportunity to the people and places that weren’t finding it on their own my work for some time, now on an international basis.

Brooks’ lament about the loss of good-paying manufacturing jobs in places like my Michigan, the pride and dignity that go with them, and the hopes for a new “industrial policy” that will rebuild manufacturing is certainly an au courant preoccupation on both sides of our politics.

But the hand-wringing about the demise of manufacturing, proffered with the somewhat patronizing air of the well-educated now eager to show empathy for those who “work with their hands” — misses the real issue. It masks the real lament, which is the loss of high-paying jobs that don’t require much education. That is like lamenting the demise of the Irish Elk or the Dodo bird (both animals were rendered extinct when they were overrun by new competitors).

For several decades after World War II, the U.S. economy operated in splendid isolation (and we had world markets to ourselves to boot). We could make and sell whatever we wanted, including junk ‘70s cars that fell apart before they hit the road.

Today, in an evolving, highly interconnected, highly competitive global economy, what we make and sell has to be high-value and high-quality. This means there are no high-paying jobs in places like America that don’t require high skills.

This reality is well documented by Georgetown University’s Center on Workforce and the Economy, whose studies have found that 99% of all jobs created since the Great Recession that pay a decent wage, require some form of post-high school technical or higher education.

And America never really “lost” our manufacturing, as Brooks laments; it has just radically changed.

In fact, US manufacturing has been vital and growing in value for some time. Since its peak in 1979 at 22%, the share of the total workforce directly employed in manufacturing has steadily declined to 9% today.

But after adjusting for inflation, manufacturing output, or the value of the product increased more than 80% over the next 30 years. Manufacturing creates tremendous wealth that puts other people to work in the burgeoning services sectors of our economy.

With some exceptions like meatpacking and other low-skill occupations (jobs native-born Americans increasingly aren’t willing to do), manufacturing jobs today are both high-paying and high-tech, requiring technical or advanced education past high school.

Given that reality, Brooks is wrong to join the chorus lamenting our recent decades’ push to raise education and higher education attainment levels.

There is overwhelming evidence that higher levels of education attainment, and advanced degree holding, including in manufacturing-related professions, means greater earnings, as well as healthier lives, greater job satisfaction and increased civic participation!

I just came back from guiding a tour of the US industrial heartland and our work to renew it with a delegation of 20 leaders from the US and Germany. Here’s what we learned about today’s manufacturing:

- We visited now thriving, high-tech Pittsburgh (which has rebounded after its Steel industry collapse of the 70s) as a center of robotics, AI, and computer and medical science. We toured the National Robotics Engineering Center run by Carnegie Mellon University- housed in an old, emptied-out steel mill. There, the researchers told us of their work to automate everything in our lives (except self-driving cars, too hard to avoid a calamitous “black swan” anomaly that caused a death)—and they lamented the lack of the thousands of highly-trained robot and automation technicians now needed to run these systems.

- Outside Erie, Pennsylvania- a historic manufacturing hub, making products ranging from the earliest bicycles to massive locomotives—at Penn State University Behrend’s campus, undergraduate students are developing new products and processes for local plastics manufacturers in their 3-D printing lab, collecting patents in the process, and getting wildly well-prepared for good-paying jobs in today’s clean-room-like high tech manufacturing environment.

- On to Youngstown, Ohio, another former steel city, where manufacturing startups are growing out of the Youngstown Business Incubator—(part of another federally funded manufacturing innovation hub,) making the super sophisticated giant high-tech machines that spit out custom-made precision parts for today’s defense and aerospace industry.

- Finally, in Detroit, we toured Henry Ford’s 2nd great invention, after he perfected the assembly-line manufacturing process, the vertically integrated River Rouge plant where over 100 years ago, 100,000 people turned raw material dumped on the docks one day into a Model A two days later. Today, six thousand workers, men and women, in an ergonomically sound, largely automated assembly platform making America’s best-selling car, the F-150 pickup (including the electric model), in one of the greenest, most eco-friendly manufacturing facilities around.

I offer these examples to point out that manufacturing is not dead but in need of revival, and the current debate and manic talk around a new industrial policy is not about manufacturing per se.

Rather, it needs to be about whether we can organize to help all our citizens make something or provide a service that is incredibly valuable and that people around the world will pay for.

Our tour showed us that “yes,” we can still make things the world wants—which tends to be in the realm of the uber-technologically advanced, where America still has the upper hand.