Black farmers have endured over a 100 years of systemic discrimination by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. But they’re not giving up the fight.

This story was originally published by MLK50: Justice Through Journalism. Subscribe to their newsletter here.

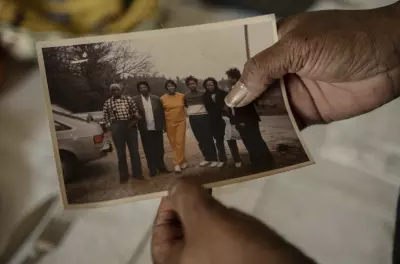

Mary Ferguson can still remember the farm where she was raised with six siblings near Bolivar, Tennessee; how her father worked the sprawling land and raised horses, chickens, goats and cattle – all while holding a job at a tannery. As children, they’d help by picking cotton and doing other chores.

At 73 years old, she cannot forget their financial struggles either. Her mother’s illness weighed heavily on her father. Banks wouldn’t give him a loan to support the farm, forcing them to sell more and more of the land. Ferguson said that her father, J.L. Ferguson, owned close to 70 acres at one point. But his land holdings had shrunk to some 20 acres by the time she graduated high school.

“Year by year, it just dwindled down until we didn’t have anything,” said Ferguson, who now lives in Memphis.

Only three acres of the family’s property remain.

Ferguson was one of nearly 40,000 farmers who applied for financial compensation through the Discrimination Financial Assistance Program created under the U.S. Department of Agriculture three years ago. The program was designed to address damages that occurred before 2021.

But she was told descendants — whose ancestors were hurt by the USDA’s discrimination but weren’t discriminated against directly — were not eligible to apply. This led the Memphis-based Black Farmers and Agriculturalists Association to sue the federal government on her behalf.

An undated family photograph of J.L. Ferguson on his land. Raising horses was the family’s passion. Each child grew up with a horse. Photo courtesy of Mary Ferguson

The case came before the Sixth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for an oral hearing late last month. A three-judge panel is expected to decide whether Ferguson and other descendants are entitled to compensation.

When someone inherits a property, they also gain all the rights and benefits of being the property’s owner, said Thomas Burrell, BFAA’s president. That includes any benefits from a legal proceeding.

By excluding legacy claims from the program, Burrell said the USDA deprived those descendants of their property rights. The discrimination claims are no different than an insurance policy or rental income from a home inherited from a relative, he said.

“This is a slippery slope,” Burrell said. “Property is property, whether it’s real or personal, whether it’s a bank account or a farm.”

Mary Ferguson’s brothers, Robert and Cecelious, ride their horses on the road that ran through family land in a 1986 photo. Photo courtesy of Mary Ferguson

It’s the latest installment in a long-running battle for economic justice between Black farmers and the USDA. For decades, these farmers have struggled to access financing from the federal agency that would help operate, improve or expand their farms. Racist lending practices are one of the reasons researchers believe Black-owned agricultural land declined by 90 percent over the last 100 years.

Hundreds of Black farmers sued the agriculture department in 1997 in a historic class action. Although a settlement was reached in the case Pigford v. Glickman, the relief only applied to discrimination claims over a 16-year span and left the USDA’s discriminatory practices intact.

The federal government has continued making funds available to Black farmers for past discrimination through other programs, including more than $2 billion for DFAP, the program Ferguson was prohibited from accessing.

BFAA argues in court records that excluding legacy claims is inconsistent with past debt relief efforts and extends a history of unfairness by the USDA. The association also said the application process was stricter than past programs. The application, for example, was 40 pages long compared to three pages in the Pigford settlements, and there’s no way for farmers to appeal if their claims are denied.

In court records, the association’s lawyer argued that barring descendants from consideration was not what Congress intended when it passed the law.

While a lower court judge disagreed with that argument, the appellate judges are expected to weigh in on the lawmaker’s intent, Burrell said.

Mary Ferguson holds an old photograph of her family on their land when her father was still alive. From left: J.L. Ferguson and his daughters Imogene Cox, Hortense Parham, Sandra Westland, Arnetta Wheeler and Mary. Photo by Andrea Morales for MLK50

Meanwhile, the descendants of farmers like Ferguson can only wait. Now retired after working in admissions at the University of Memphis, she said she feels an obligation to seek answers because she’s the youngest of her living siblings.

She had never tried applying for USDA compensation before but remembered stories shared among brothers and sisters about their father’s struggle to get a loan as an undereducated man.

Many of the land sales have been nearly impossible to track. But Ferguson found a record of one land sale recorded in 1975. Her father was paid about $2,800 for 55 acres, about $13,500 today. By comparison, the appraised value of the family’s three acres is $8,200, according to property records.

The price was too low in Ferguson’s opinion. The sale records are also an example of how other parcels might have been sold, she said.

“Being poor and then trying to maintain what you already have — it was just like giving (the land) away,” Ferguson said. “I don’t feel that’s just when that land could have been inherited by me as a daughter.”

Michael Finch II is the enterprise reporter for MLK50: Justice Through Journalism. Contact him at [email protected]