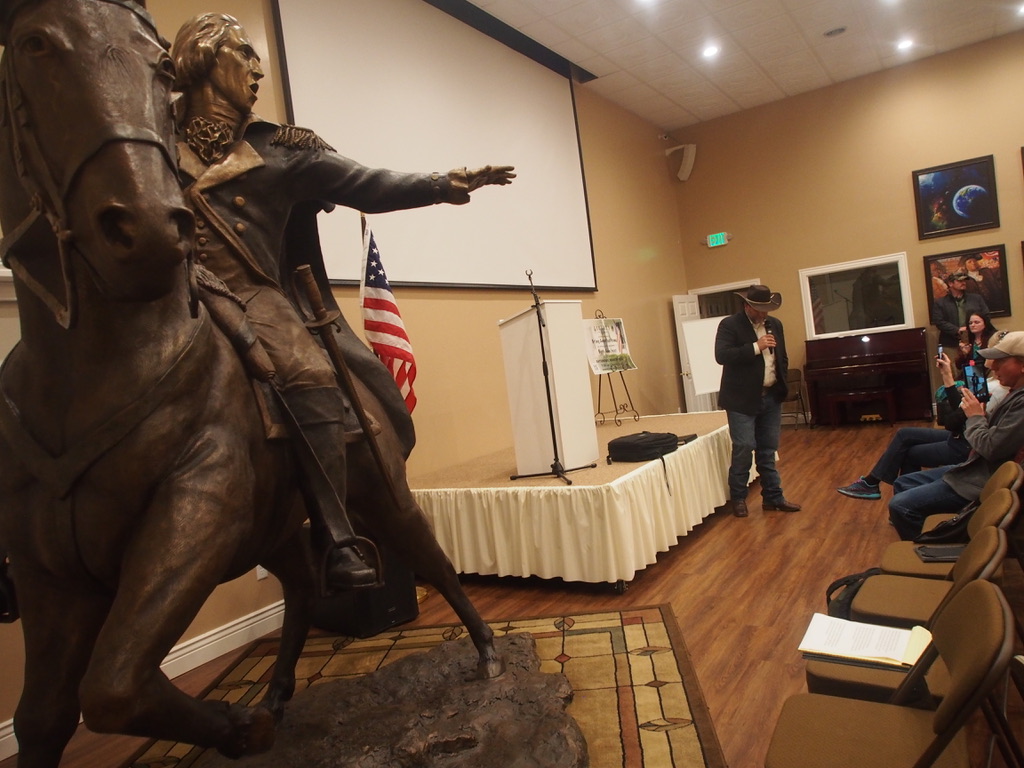

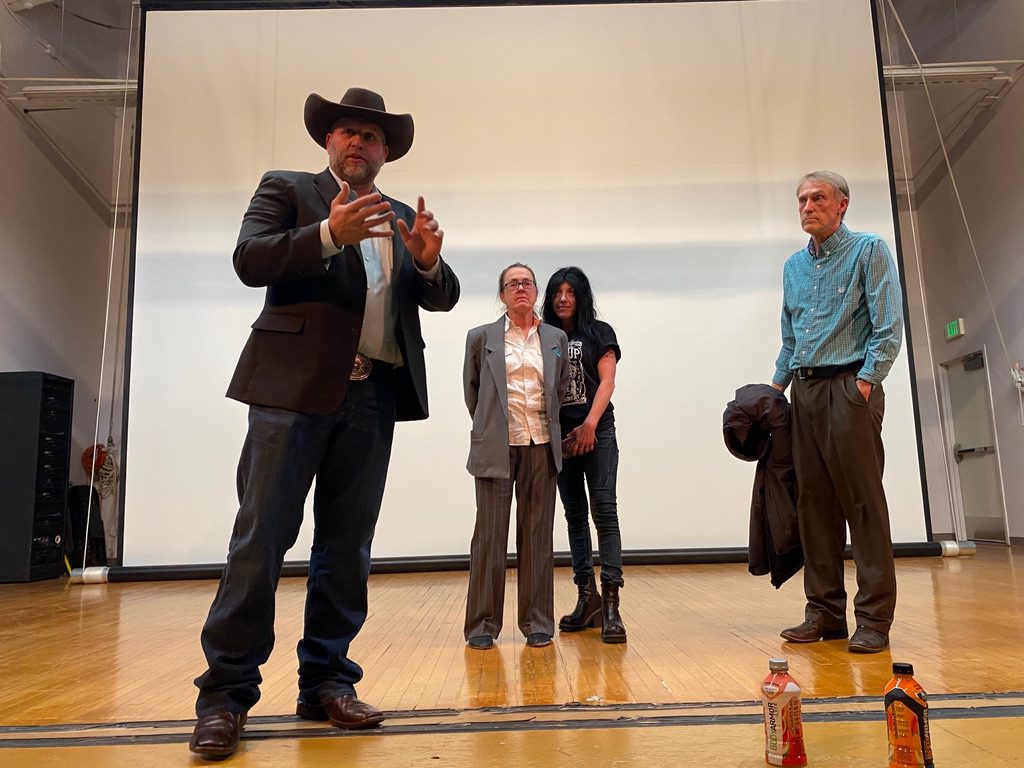

Ammon Bundy is in his usual cowboy hat, black blazer and jeans. He’s standing, mic in hand, inside a replica Colonial-era brick building next to a life-sized statue of George Washington astride a horse.

It sounds like a cliché scene in some lame Hollywood version of the far right, but it’s real. More important than the over-the-top trappings is the large crowd at Ogden, Utah’s Liberty Hall for Bundy’s speech.

It’s the second of 11 stops on a 12-day anti-government barnstorming tour for Bundy. Like many in the militia and broader Patriot Movement, he’s had to adjust his strategy after getting deplatformed and has ramped up his in-person events. But the backlash from the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection hasn’t cooled far-right rhetoric and hasn’t dampened interest in it, if the near-capacity crowds on Bundy’s first two stops are any indication.

The crowds are a mix of young and old and even some families with children in tow. These are not, for the most part, hardened militia members. In fact, they look like the crowd that stormed the U.S. Capitol in a haphazard attempt to overturn the 2020 presidential election.

What binds those who come to see Bundy (all unmasked, in violation of a Utah mandate) is that they, like he, seem to have given up on government completely and are searching for direction. Bundy is happy to provide that.

“We will find remedy is where remedy has always been found in the security of our liberty, and that is with each other with our neighbors.” – Ammon Bundy

“We are not going to find remedy to the security of our liberties in Washington, D.C., we are not going to find remedy to the security of our liberties at the Utah Capitol building, we are not in the legislature with the governor, and unfortunately we are not going to find it with our local governments,” Bundy said. “We will find [that] remedy is where remedy has always been found in the security of our liberty, and that is with each other with our neighbors.”

What he means is, the government is the enemy and laws you deem unconstitutional don’t apply to you. And when people think the law doesn’t apply to them, what’s left but conflict? That message is resonating with many Americans.

Bundy’s tour is promoting his anti-government network, called People’s Rights, which has grown to tens of thousands across the country, according to experts who track far-right groups. By Bundy’s estimate there are 50,000 members across 36 states, far past its original western strongholds, to places such as Wisconsin, Illinois, Michigan and even to the Eastern Seaboard in North Carolina.

Far-right influencer culture

People’s Rights is one of many networks that have built up in the open on social media platforms and now are operating largely in the shadows after many websites banned anti-government groups.

Cristina López G., a senior research analyst with Data & Society who studies political disinformation, says these groups grew and metastasized in online echo chambers where social media algorithms incentivized inflammatory speech. She likened it to social media influencers seeking more and more dramatic photos.

“(It’s) right wing, far-right influencer culture, but influencer culture, nonetheless, that in order to get more eyeballs has all the incentives to escalate the rhetoric,” she said.

The Capitol insurrection was really just a physical manifestation of an online gathering that had been building for years.

“That was like a Comic-Con of an entire movement that got there through different streams of (online) content,” Lopez G. said.

Lopez G. thinks de-platforming has cooled the temperature but that extremist groups retreating into the shadows could be a double-edged sword.

“These small closed spaces can also become incubators for radicalism, they can become quicker ways for folks to be siloed and isolated into groupthink that only escalates in extremism,” she said.

It’s also harder for law enforcement to track. And the potential for more political violence is likely to be with us for a while.

Amy Cooter, a professor at Vanderbilt University who studies paramilitary groups, said prominent militia groups such as The Oath Keepers and Three Percenters, whose members were tied to the insurrection, may lay low for a while given the negative attention.

“But I think that there’s a high probability that some of the smaller groups are still waiting for, from their perspective, the right moment to act,” she said.

In Washington, some politicians have talked about a response similar to the one following the attacks of 9/11, including creating harsher penalties for what is deemed domestic terrorism. That could have unintended consequences, including harming other activists and pushing anti-government groups who have been peaceful to more radical action, Cooter said.

“I don’t think it would be particularly effective. I’m afraid it would be actively harmful,” she said. “That’s exactly the kind of thing that is a harbinger of doom for them, that may very well serve as a massive radicalizing force.”

Where does this end?

Bundy has a go-to John F. Kennedy quote: “Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.”

He deploys it during speeches and when asked by reporters about the possibility his anti-government action could lead to violence. He said it twice to me during an interview in an Emmett, Idaho diner on a chilly winter morning just before his Utah tour.

For Bundy, it’s not a throw-away line. He’s been at the center of two armed standoffs with federal authorities, one of which turned deadly. The Capitol insurrection has not chastened him or others in the movement. Quite the opposite.

At one of his Utah speeches, a woman in the crowd asks for advice on how they can fight the government without sparking a civil war. Bundy seems to reject the premise.

“The answer is simply, we only act in defense; we do not instigate we do not try to force or change something that is not going to change; we defend,” he said. “And if then, at that point, they push it to the point where we have to defend ourselves enough that they call it a civil war, then it is justified.”