“I’ve loaded more coal in my sleep than I have in the mines,” says Terry Lilly. The words don’t come easy.

Though retired, Lilly remains ever a coal miner. It’s said coal miners are a stoic sort. Inner revelations aren’t in Lilly’s nature. But it’s also physically difficult for him to share those words.

Black lung has seen to that.

Lilly went underground in 1975, at 18. Thirty years in, shortly after returning from hernia surgery, he was buried in a collapse. “I broke a leg, both knees, a hip, my back. And while I was in the hospital, I had blood clots go through my lungs. I lay in ICU for 18 days. Should have died.”

Meanwhile, a physical had revealed spots on his lungs. He was initially misdiagnosed, as so many coal miners are, with lung cancer. After a biopsy at the University of Virginia, a doctor stepped into the waiting room and asked Lilly’s wife, “Ma’am, did your husband work in a dusty environment?” “She said, ‘Yeah; he worked in the coal mines for 30 years.’ ‘That’s your problem,’” the doc said. Black lung.

“Listen, these hands are as handy as they can be,” Lilly says. He’d spent a lifetime tinkering, tilling, restoring automobiles. But simple chores grew incrementally more difficult, and with that a deep-seated despair crept in, compounded by a tragedy.

At 3:37 p.m. on April 5, 2010, at Massey Energy’s Upper Big Branch mine in Montcoal, West Virginia, 29 men died in an explosion 1,000 feet below the surface. He had worked alongside those men. “I was very close to all them boys.”

What Lilly has endured – debilitating injuries, the death of dear friends, the slow choke of black lung – is, tragically, not so uncommon. That he sought help in addressing it is.

“What started it was my wife, she got concerned, because I didn’t want to get out of bed,” he says.

Drew Harris is medical director of the Black Lung Clinic at Stone Mountain Health Services in St. Charles, Virginia. He oversees a study believed to be the first to examine mental health issues in a large population of coal miners in the United States.

Nearly 3,000 coal miners completed a survey. The results revealed that more than 1 in 3 suffered symptoms consistent with major depressive disorder. Almost 4 in 10 experienced significant anxiety. More than 1 in 4 had symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. And more then 10% had contemplated suicide in the past year – four times the rate for men in Virginia overall.

“Just asking the questions opened up opportunities,” says Jim Werth, a psychologist who while at the Stone Mountain clinic launched the initiative. He was stunned by how many confessed to suicidal impulses. “Because they’d never been asked the questions, it had never come up.”

In Eastern Kentucky, West Virginia, Southwest Virginia, a coal miner rises well before dawn. It’s perhaps an hour or more drive to the site. A 10-12-hour shift, not uncommonly in a three-square-foot enclosure, under incessant threat of collapse, asphyxiation, explosion; never seeing the light of day. Six, seven days each week, 30-plus years, toxic dust infiltrating his lungs.

He then emerges, to retirement if he’s lucky, lungs besieged, essentially, in the words of black lung researcher and advocate Dr. Robert Cohen, “suffocating while alive.”

David Bound, 75, went in at 18 and mined for 34 years. “Every now and then,” he says, “I’ll bail out of bed. My wife will say, ‘What’s wrong with you?!’ ‘Oh, honey, the top was falling.’ You relive the top falling in on you, and you bail out of bed trying to get under cover.”

Historically, true to their temperament, miners have been reticent about their emotional scars. Many who have suffered are now opening up.

Heading into the darkness.

With the introduction of federal regulations 50 years ago, the number of miners stricken with black lung had long been in decline. But by the early 2000s, diagnoses were once again climbing, most particularly the most severe form: progressive massive fibrosis.

As mining techniques have evolved to make it possible to extract increasingly hard-to-reach coal reserves, miners are drilling through denser masses of stone and are thereby exposed to silica dust. Silica dust is extremely fine, easily inhaled, more toxic than coal dust. It remains trapped in the lungs. It’s deadly.

Ray Branham, 63, figured he’d work in the mines for maybe three years, “get what I wanted,” and get out.

His dad was a coal miner. “He talked to me about it. I’ll never forget one of the things he told me. He said, ‘Buddy,’ he said, ‘let me tell you.’ He said, ‘Once you start, you’ll never quit. They’ve got you.’”

At night, he could hear his dad’s labored breathing. When he died of complications from black lung and cancer, Branham was already in; he remained so until back trouble brought him out a little more than a decade ago. His breathing grows increasingly labored; he’s awaiting a diagnosis.

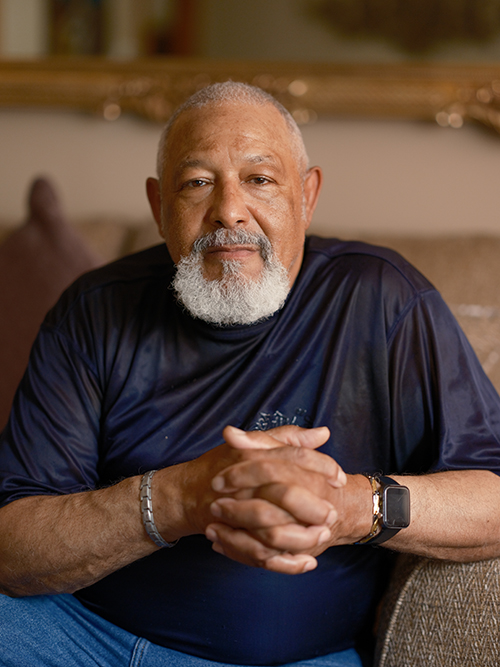

“I knew that he was sacrificing himself to give us the American Dream,” says Vonda Robinson of her husband, John: 27 years in the mines.

Such young men (around 95% of coal miners are male) were aware of the risks. But, says Bounds, “When we first went in the coal mines, every one of us thought we were six foot tall and bulletproof. We weren’t getting black lung.”

“I knew that he was sacrificing himself to give us the American Dream,” says Vonda Robinson of her husband, John: 27 years in the mines.

In his job interview, she says, John was asked, “‘Why do you want to work for us?’ And he said, ‘Because I want to give my family the American Dream. I want a nice house, car. I want to give my family nice things.’”

Avenues in Central Appalachia to that dream were, and remain, few.

“I’m either going to bag groceries, flip hamburgers, or go into the coal mines,” a teenage John Robinson told himself. His viable options came down to going “on top of the mountain and stripping the coal off,” or going “underground and mining it out. I chose underground.” Underground, he learned, offered top dollar.

Mines operate in a culture of self-reliance forged in a trust of the miner beside you. Veteran miners take novices under tutelage. When Lilly first arrived, he was mentored by a man who also wrestled on Saturday nights in nearby Oak Hill, West Virginia, under the name Black Diamond.

“He told me, he said, ‘Boy, I’m going to give you a piece of advice. Learn to run every piece of equipment in this mine and you’ll never be without a job,’” Lilly recalls. “I learnt to run a buggy, I’d slip over to a bolter, and then I’d go run the [continuous] miner.”

He thus made himself indispensable. Until such time as he was dispensable. When he received his black lung diagnosis, after having been injured, he’d missed more than two weeks of work and was terminated.

Coming out into the light

Paul White’s ascent from the mines of Eastern Kentucky was abrupt. His descent into depression, likewise.

White, 61, had been a miner for a decade and a half, when in 1985 a two-square-foot section of wall fell on him, jarring his brain’s cerebellum. For a time, he couldn’t even stand. It was uncertain if he would ever walk again.

White and his wife had just had their third child. “New home, new car. I was making good money. Twenty-five years old … you’re at the top of the world.”

“From the time I was 8, 9 years old, I’d had paper routes and mowed grass,” White says. “I always took a lot of pride in my ability to work.” He was suffering physically, mentally, and emotionally (and would later be diagnosed with black lung).

For so many miners, that loss of identity is devastating. Arvin Hanshaw, 67, went in as a teenager and remained 37 years. When his health forced him to leave, his wife went to work as a caregiver. “I’d promised her that I’d take care of her,” he says. “I’d promised her dad I’d take care of her.”

“See, we were brought up that we take care of the family,” says Gary Hairston, president of the national Black Lung Association. He went in at 20, in 1972, and labored for almost 28 years. When you can no longer work, Hairston says, “You tell yourself, ‘You ain’t no man no more.’” Or, “‘It ain’t nothing the matter with you; it’s just your lungs.’”

Equally debilitating is the severing of a bond. “All your buddies, your family – they’re just like your family,” Lilly says. “I went through divorces with guys … You go through what they go through because you’re a family.”

Robinson was known to his fellow miners as Big John: a six-foot-five granite slab of a man. He lives with advanced black lung; nearly died from blood clots; has had neck, shoulder, back, and knee surgeries; arthritis in his feet. But the absence of that brotherhood has been every bit as painful.

“Those first five years,” says Vonda, “oh, dear, Lord.” John would see miners, in uniform, heading off to a day’s work and break down. “He’d sit and cry,” she says, “and I’d cry with him.”

Reaching out

The Black Lung Association assists miners totally disabled by the disease gain access to their state and federal benefits – an often-grueling undertaking – and advocates for improved health and safety standards within the mines. It’s also recently turned more attention to mental health issues.

At the West Virginia chapter’s annual conference in May, a panel of retired miners with black lung shared their challenges. A similar panel will be convened at the national conference in September.

Doris Broach lost her husband to suicide in January. Tom was “not one to let you know things,” Doris says.

Tom Broach’s proximate cause of death was a gun to his chin. But arguably, it was black lung, decades of inhuman toil, a burden a man shouldn’t be tasked to shoulder: immediate, intermediate, and contributory causes of death.

“He was a hard worker,” Doris says. “It was nothing for Tom to go out for 18 hours, try to get two hours sleep, and go back again.” Away from his home in West Virginia, to Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, wherever securing work dictated. “He really worked himself to death.”

In those final months before the gunshot, Doris was in a nursing home recovering from a fall. Tom was home, alone, despondent.

“If he would have opened up,” Doris says, “to share with us what his feelings truly were. If he had just opened up.” Then, maybe, they could have sought help.

Drew Harris at Stone Mountain’s black lung clinic acknowledges stigma has historically been a significant barrier to addressing the mental health challenges of men who work in “this sort of hyper-masculine environment.”

Resilience and self-sufficiency are highly valued traits in Central Appalachia, Harris notes.

“Trying to convince someone that it’s OK to talk about what they’ve experienced and how it’s affecting them is challenging.” Miners then bring a “more intense set of factors that contribute to mental illness.”

After his injury, White was taking a handful of pills each day, which “in itself is devastating to a body,” he says. “I just didn’t want to live. And so they forced me to go see a psychiatrist.”

It took time. White, a Baptist minister, consulted the Scriptures, and in them found further substantiation for reaching out for help – substantiation that purpose lay ahead. He went on antidepressants and continued to see the psychiatrist. His mental health improved in increments.

That initial Stone Mountain survey of miners has led to a six-clinic study.

“Getting people resources is step one,” Harris says. Step two is examining how to prevent the issues from occurring. Qualitative interviews will be conducted to explore risk factors, resiliency factors, barriers to care, and preventive measures. Harris would like to see peer-led support groups established.

A critical juncture in White’s recovery was the death in the mines of a member of his congregation and the conversations he had with the man’s father, also a coal miner.

“Once you go through something yourself,” he says, “and you get through the challenge, maybe it helps you to help somebody else get through the same challenge.” He aims to shine some light into that darkness.

“I loved it”

This past March, Terry Lilly attended a first-time reunion of miners who had worked at Upper Big Branch and family members of the men who died in the explosion there.

Lilly says when he arrived, he was loath to go through the door. He’d always dreaded seeing these folks at the grocery store or Walmart. What could he say to them? His wife prodded him in.

“It had a very, very slow start,” he says. Others were likewise reticent, unsure. It was the wives who got things rolling; the men took their cue. “The ice broke. There were a lot of people hugging and crying. Nobody spoke about the accident. But we all talked about old times and the people you worked with – and, man, it really got good then.”

“Afterwards, I felt pretty good about it. I felt like, that’s a pretty good deal,” he added. Another gathering is tentatively planned for late summer or fall.

Lilly had been seeing a psychiatrist since 2006, the year of his accident, “and when the thing at Upper Big Branch happened, that just piled more on. I was having trouble because I couldn’t comprehend. I couldn’t do nothing. And it took a long time to get me back out in the garage to do things I enjoy.”

“I deal with it, but I still have days I don’t feel good,” he says. “There’s just times you get to thinking …”

“My wife says she can always tell,” Robinson says. “She says, ‘You get real quiet. You don’t say nothing. You kind of draw back from everybody; pull back.’ Sometimes we just sit and talk.” He keeps himself busy on their hobby farm. “You just gotta stay busy. You’ve got to stay busy.” His wife, Vonda, now serves as vice president of the national Black Lung Association.

Hairston keeps himself occupied with his duties as the association president and with work around his home. But, he says, “Everything I do is in moderation.”

“I loved coal mining. I did. … I loved it, but I had to give it up. And it’s just like … it took a big part of my life. Something was now gone. A big part of my life was now gone.” — John Robinson

Hanshaw takes meds for depression and anxiety and shares what he’s experiencing with his buddies. “It does us good to get together and talk about things. We help each other out.”

When Lilly’s son graduated from high school, he was weighing the option of going into the mines. Lilly told him, “‘I’m gonna tell you something, and I mean what I say. If you mention this again about the coal mines, we’re gonna have to go to the emergency room.’ He said, ‘Why is that, Dad?’ I said, ‘So they can get my foot out of your hind end. You’re not going in the coal mines.’ And I meant what I said. I’d have gotten him into a headlock or whatever it took.” Thus ended that thought experiment.

But it’s complicated. More than a few miners will tell you that while they have, or would, discourage their children from coal mining, they feel it’s ultimately their own decision. They’ll certainly warn them of the considerable risks. But they acknowledge the allure of a relatively well-paying job and health care, a foundation on which to start a family in a region that offers so few opportunities.

And many, maybe most, will tell you the rewards, beyond monetary, were considerable.

“I loved coal mining. I did. I loved it,” Robinson attests. He loved the nature of the work, its challenges. Camaraderie. Purpose. “I loved it, but I had to give it up. And it’s just like … it took a big part of my life. Something was now gone. A big part of my life was now gone.”

Coal miners “sacrifice themselves, literally, their physical health, to be able to support their families,” Harris affirms, and with that comes a mental and emotional toll. He’s witnessed generations of men who’ve suffered from black lung, ladened with foreboding: “My dad and granddad died with black lung, and that’s my lot” – a culturally hereditary disease.

An ingrained abhorrence to any hint of weakness. A sense of “this is my burden to bear.” That stoicism. These surely account for much of the reluctance to reveal the costs.

But maybe that perceived stoicism is overstated. Maybe it’s that no one’s been asking the questions. They’re now being asked, and coal miners are speaking up. As John Robinson urges, “We’ve got to make some noise.”