Pittsburgh, steel yourself for the new Iron City.

Pittsburgh Brewing Company now belongs to 62-year-old J. Clifford Forrest III, the Fox Chapel coal magnate who founded Kittanning, Pennsylvania-based Rosebud Mining.

Forrest’s name might ring a bell. When a storage tank leaked a licorice-smelling coal-cleaning chemical into the Elk River just northeast of Charleston, West Virginia, in 2014, Forrest’s chemical holding company owned the industrial polluter behind the leak.*That company, Freedom Industries, caught flak for not immediately reporting the spill, which left some 300,000 people without tap water for several days and sent at least 300 people seeking treatment for exposure to the chemical.

Forrest also made headlines in 2016 for donating $1 million to President Donald Trump’s inauguration fund, more than every other donor in Pennsylvania combined. He has a long history of political donations, mostly to Republican and some pro-coal Democratic candidates, as might be expected from a man who owns 18 underground coal mines and six coal preparation plants in Western Pennsylvania and Eastern Ohio.

Now Forrest is a beer man.

PBC was founded in 1861, but its beer hasn’t been brewed in the City of Pittsburgh since 2009. At its height, Iron City had a 43 percent market share, Forrest said. Today, PBC says it’s down near 3 percent, as it contends with big macro beers like Bud Light as well as Pittsburgh’s blossoming, 30-strong, locally owned craft brewery community.

Forrest has pumped millions into local advertising and rebranding efforts, and he has a deal in place to purchase back the original 8.95-acre Iron City Brewing compound in Lawrenceville, with plans for a new brewpub, retail complex, restaurant, office space, outdoor concert venue, and more.

Market challenges aside, Iron City evokes a sense of civic pride and nostalgia that’s difficult for Pittsburghers to resist. This 150-year history is PBC’s trump card, and it’s at the center of the company’s renewed marketing strategy: remind the city — especially millennials — that Pittsburgh and Iron City are one and the same.

“We have a good product, and we have this great history, and where I think there’s great opportunity is to exploit a couple generations that don’t know much about Iron City,” Forrest said. “It is an authentic brand, and it has history, and I think the millennial generation appreciates that type of stuff.”

If not millennials, who drinks Iron City? That’s the question PBC’s director of sales and marketing, Chad Primrose, faces every day.

“When Cliff bought it, I would say the people drinking Iron City were old-school yinzers, blue collar guys — you know, insert any stereotype you want for Pittsburgh — that’s the only people who were drinking it. It was a small base. IC Light would probably be tied to people that just love Pittsburgh, all they care about is Pittsburgh.”

“We’ve been trying to shift that,” he continued, “and that’s tough to do in the beer business, but what we’ve been noticing is craft beer drinkers, a Yuengling drinker, someone like that, you get them to try regular Iron City in a blind taste test, and more often than not we come out on top.”

Primrose said PBC’s annual output is around 1.5 million case equivalents, which is less than in years past. But distribution is up, with 100 new draft locations in parts of Allegheny and neighboring counties since partnering with a new local distributor, Frank B. Fuhrer Wholesale, last summer.

“Usually if you fall off, there’s no coming back,” Primrose said. “No matter what you do, you get a stigma attached to you: you’re an old man’s beer, you’re a grandpap’s beer, and no one wants to try you. So we’re trying to climb up this hill to be relevant to the young people, let them know that it could be cool to drink IC Light and drink Iron City.”

Primrose and Joe Avi, PBC’s director of business development, are the only new employees besides Forrest. In the early 1980s, the brewery employed over 300 union workers. In 2007, members voted to approve a $5 million reduction in their contract to keep the plant in Pittsburgh, only to see brewing halted in 2009 and moved to Wisconsin-based City Brewing Company in Latrobe, ending a nearly 150-year span when Iron City Beer was brewed in Pittsburgh.

PBC has 16 employees, and while it retains a brewer on the payroll, today it’s a marketing and sales company, with 100 percent of its beers still contract-brewed at the old Rolling Rock facility in Latrobe.

Forrest said he learned Pittsburgh Brewing was for sale while pursuing investments outside the coal industry with Wexford-based investment firm Tecum Capital.

“They didn’t expect me to have any interest in it,” he said. “Growing up in Pittsburgh, it’s an iconic name in our region. That’s what perked my interest: the history of the brand and the business.”

Forrest, a graduate of North Hills High School and the University of Pittsburgh, bought the Pittsburgh Brewing Company brand in January 2018, unaware that he also would have an opportunity to purchase the historic compound next to the Herron Avenue Bridge along Liberty Avenue in Lawrenceville. Since 2009, Pittsburgh Brewing has rented office space inside one of the enormous red brick structures on the site, the oldest of which dates back to 1884.

After several meetings with the current property owner, Jack Cargnoni of Collier Development, PBC signed a deal that is contingent upon finding a new 3-acre site for two public infrastructure companies Cargnoni owns and needs to have located in the city.

Forrest and Cargnoni have met with the city’s Urban Redevelopment Authority, and Forrest says despite this one contingency, he is “extremely optimistic” the deal will be completed as soon as March or April of this year.

“The URA is supportive of a vibrant, mixed-use development at the Pittsburgh Brewing site that is responsive to the community’s needs and concerns,” URA spokesperson Gigi Saladna said in a statement. “We’ve had a few discussions with Mr. Cargnoni and look forward to receiving more information on his site specifications.”

Assuming the purchase goes through, Forrest plans to turn the “Ober Haus” building and banquet room along Liberty Avenue into a brewhouse-type pub, where test batches and smaller runs of PBC’s Block House craft beer can be brewed on-site. Production of Iron City, IC Light and other beers will continue to be contract-brewed in Latrobe.

In the old Keg House, constructed in 1896, Forrest envisions a standalone restaurant. He’s also considering retail shopping and believes that some of the larger buildings could make for “very cool office space.”

PBC would also like to have a small concert venue in the outdoor courtyard between buildings.

“It would be great to have the ability to have Oktoberfest parties, concerts on weekends,” Forrest said, adding that these were “broad-brush ideas that need to be firmed up.”

“We were worried about the people of Polish Hill being upset,” Avi said, referring to the adjacent community. “Well, they’re ecstatic. … It’s a huge – I say hipster without it being insulting – but it’s a huge hipster community, and they’re excited to see the brewery going back in.”

Kim Teplitzky, president of the Polish Hill Civic Association, said that she’s unaware of new ownership approaching her group, but added that they could have spoken with residents individually.

“We’d love to be able to be part of the process,” Teplitzky said. “Our organization would love to talk with the new owners about what their vision is, and the things we think would be most beneficial for the area.”

Matthew Galluzzo, executive director of the Lawrenceville Corporation, said he’s been introduced to the new owners and is waiting for the sale to go through before having more meaningful discussions. He added that the site sits at the the intersection of four neighborhoods in Pittsburgh’s East End, “so seeing a productive reuse of that site — whatever that means — is really important to us as a neighborhood.”

“If we can’t win Pittsburgh, we’re not going to win anywhere else.”

Iron City was to Pittsburgh as Old Style was to Chicago; as Schlitz was to Milwaukee; as “Natty Boh” was to Baltimore.

“Every major city has an old vintage yellow beer brand that made it famous,” said Steven Grasse, founder of Quaker City Mercantile, “and if you do it right, you’ll have great local sales and relevance.”

Grasse’s company invents, markets, and distills its own spirits, and it has also developed a niche revitalizing classic beer brands, like Hamm’s, Miller High Life, and Narragansett. He also met with previous Pittsburgh Brewing Company owners to discuss a potential marketing deal.

“I feel like a brand like Iron City, what it does have going for it – the only thing it has going for it – is its history,” Grasse said. “Its history needs to be handled very deftly and with a certain amount of nuance so that it actually resonates with consumers.”

It’s not enough to sell the history of the brand, he argues, but the history of the city it comes from.

“What you want to do is build that ideal story in people’s minds about Pittsburgh, its heyday, its golden era, and that will translate anywhere in the world because its authentic to that place,” Grasse said.

German immigrant Edward Frauenheim created Iron City Brewery in 1861. By 1899, 21 breweries amalgamated into the Pittsburgh Brewing Company, becoming the third largest brewery in the country.

Leslie Przybyłek, senior curator at the Senator John Heinz History Center, said that after World War II, the beer industry underwent a period of extreme consolidation, leaving Pittsburgh with two breweries standing: Pittsburgh Brewing Company and the South Side’s Duquesne Brewing Company.

Przybylek said Pittsburgh Brewing began to distinguish itself in 1963, when it, in conjunction with Alcoa, introduced the first ever pull-top can. Duquesne folded in 1972, and not long after, PBC began to issue commemorative cans to celebrate the Steelers and Pirates world championships, cementing Iron City’s legacy as Pittsburgh’s true and only beer.

It’s upon this legacy that the new Iron City hopes to resurrect its once-iconic brand.

In spring 2018, Pittsburgh Brewing hired Millvale-based marketing consultant Top Hat to handle a brand relaunch. The message, from Forrest, was clear: Win back the city.

“We don’t want to do anything that’s not authentic with the DNA of Iron City,” Top Hat founder Ben Butler said.

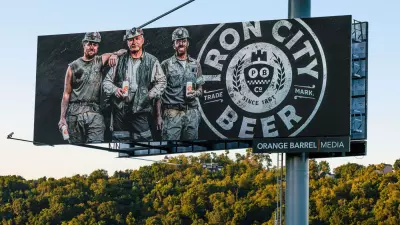

First came a social media campaign to tease the upcoming relaunch — “simple, iconic shots of Iron memories to remind Pittsburgh why they love it.” Then came a TV spot, during the first Pittsburgh Steelers preseason game. Then, 40 billboards across Allegheny County, up for four to six months apiece, to promote the revamped Iron City Beer, some with nothing more than the revampednew red bullseye logo and others featuring soot-covered miners from Forrest’s Rosebud Mining posing with crisp white cans of Iron.

To reach new, younger audiences, Pittsburgh Brewing announced a deal with web-series star “Pittsburgh Dad,” aka local actor Craig Wooten, who starred in a remake and parody of a classic Iron City commercial. It announced an exclusive merchandising deal with Steel City Clothing, which held a contest to win an “Iron Throne” of 1,861 bottles and cans of Iron City.

Pittsburgh Brewing also entered into a partnership with IheartRadio and pop music station 96.1 KissFM’s morning show, and they’re making a commemorative can to mark 102.5 WDVE’s 50th anniversary as a rock music station.

There are also plans for new beers. A dry erase board in the Pittsburgh Brewing offices sketched out an idea for a “Malt 69” in a can that opens at either end. PBC plans to revive IC Golden Lager this spring with Troy Hill’s Penn Brewery, Avi said, and it’s also bringing back a version of the IC Light Twist Rio Cherry, along with a lime-coconut version, both developed by longtime PBC brewer Mike Carota.

When it comes to Pittsburgh Brewing’s advertising budget, it’s only going to get larger. “Our spend is going to be in excess of a couple million dollars this year, which is probably an increase of over 100 percent of what it was last year,” Forrest said.

PBC’s marketing push can be distilled down into a slogan that features prominently on Iron City’s new packaging, cans, and billboards: “family owned, brewed here.”

Primrose said that “brewed here” means brewed in the United States. TopHat’s Butler said it’s a “double entendre” that can mean Western Pennsylvania when read locally, or, in a different market, brewed in the United States.

Both Avi, a longtime friend of Forrest, and Primrose praise Forrest’s character and humility, readily sharing stories of elaborate meals he’s prepared for his staff and other moments of generosity. At a recent tailgate thrown by PBC before a Steelers game in the Heinz Field parking lot, Primrose said that Forrest hung back to sweep up trash, telling the others he’d meet them inside.

As for “family-owned,” none of Forrest’s family works at Pittsburgh Brewing; however, Primrose said that because the company doesn’t have the money to invest in focus groups, they will bounce ideas off Forrest’s 18-year-old son to see if an idea will resonate with a younger audience.

“We’ll go to him because he’s going to be in that demographic,” Primrose said. “Hey, what about this idea? Do kids listen to Kiss FM? At 18, you know what the 21-year-olds are doing, because that’s what you’re aspiring to be. That would be the family end of it.”

“The last two owners were private equity guys,” Forrest said, “so, I think that just wanted to establish the fact that this is locally owned, and I have a couple younger children who are beyond excited about the prospects of growing Iron City … it’s never going to be what it used to be, but I think we can grow it by multiple, two to three times from what it is today.”

How much Pittsburgh cares about where Iron City is brewed and who owns it will be measured over time in sales of six-packs and kegs. In the meantime, the message being broadcast to the city is clear: if you like the Steel City, you’ll love an Iron City.

“The outlying counties, there’s certainly lots of potential,” Forrest said, “but if we can’t win Pittsburgh, we’re not going to win anywhere else.”