Back in 2006, when Scott Shuford was Asheville’s planning director, he reluctantly accepted an invitation to attend a meeting about the impact of climate change on local governments.

“I didn’t see how a two-degree temperature change could affect the community,” he recalled, referring to the predicted rise in earth temperatures in years to come. “But I agreed to attend, thinking it would only be about 15 minutes.

“After about an hour-and-a-half I came out of the meeting drenched in sweat.”

All the plans he had drafted up to that day suddenly seemed to have overlooked a future fraught with unanticipated challenges. Those 2 degrees of temperature change meant greater threats of weather extremes — of torrential rains, floods, and landslides, and extended drought and wildfire.

“We weren’t ready,” Shuford said of Asheville’s infrastructure at the time. “We still had stormwater pipes made of oak trees from 100 years ago.”

But none of those natural threats holds the potential to alter Asheville and its surrounding counties as much as a different one: People moving to the region from other areas, many seeking escape from potential natural disasters like floods and wildfires.

Asheville Booms as “Safe City”

“Asheville is becoming known as a ‘safe city’,” said Mary Spivey, community manager of The Collider, an organization for local professionals engaged in climate services. “Many people are starting to migrate here and are using that term. Many others are claiming a spot so that they may come here when they feel they need to.”

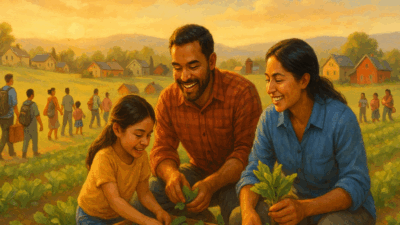

The region has long attracted residents for its temperate, year-round climate, recreational amenities, open spaces and — until recently — its relatively moderate living costs.

Between 2010 and 2019, Buncombe County’s population rose more than 10% to more than 260,000, U.S. Census Bureau estimates show. That’s more than double that of the state’s population growth.

Some forecasts predict that greater Asheville’s population will balloon by another 50,000 people by 2080.

Heading for the High Ground

Florida State University sociologist Mathew Hauer estimates that many people will come from such coastal cities as Miami, New Orleans, Charleston, Savannah, Boston. The reason: Sea levels by the end of this century are expected to rise one to eight feet — enough to displace as many as 13 million coastal dwellers, according to Hauer’s calculations.

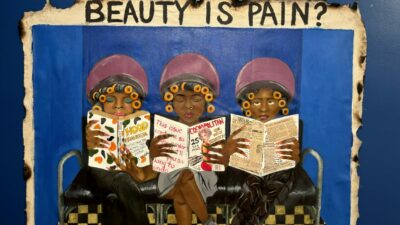

That total would more than double even the so-called Great Migration of Blacks fleeing racial bigotry in the south in the first half of the 20th century.

Others will come to the Western North Carolina mountains from inland parts of the south to escape increasingly suffocating summer temperatures.

The pandemic also may accelerate this migration because many people have adapted to working remotely.

“Now you have the ability to work where you live rather than having to live where you work,” said Shuford, who is now with CASEconsultants International, an Asheville firm that advises governments, and corporations on dealing with climate change.

“So how many times are you going to see your house in California burn until you’re going to decide to move to a place where that’s not an issue?”

A Great Migration

Early indicators of a population surge may be seen in the recent decisions by such corporate giants as Eaton Corporation, Amazon, and Pratt & Whitney to make multimillion-dollar investments here, with promises of creating high-salaried work forces.

Ben Teague, former director of the Asheville/Buncombe Economic Development Coalition, said that corporate investors historically considered such factors as land and labor costs, a talented workforce, quality of healthcare, and public safety.

“Weather never seemed to be there,” said Teague, now the director of Strategic Development for Biltmore Farms, which recently enticed aerospace giant Pratt & Whitney to build a $650 million manufacturing plant on its land. Teague said. “Now it’s more prevalent.”

Teague said the increased frequency of “billion-dollar weather events” makes clear that coastal investments in the southeastern United States carry high risk.

Local experts warn, however, that none of this should be taken to mean that Asheville as a “climate-migration winner” has little to fear.

“The broader question is whether Asheville’s growing reputation as a ‘safe city’ will trigger growth that might threaten its essence [because of] new development, traffic and all the pressures attendant to growth.”

The most recent North Carolina Climate Science Report foresees Asheville and its surrounding counties experiencing higher temperatures and heavier rain. This combination triggers more flooding and landslides.

Conversely, hotter temperatures can also bring on drought, which impacts agriculture, water supplies, and wildfires in tinder-dry forests.

In 60 years if nothing is done to slow global warming, according to the report, Asheville’s average temperature will be 9 degrees warmer.

Even if current measures to reduce greenhouse gases succeed in slowing the temperature rise, Asheville’s climate will be 3 to 5 degrees higher.

“Asheville is not immune,” said Karin Rogers, acting director of the National Environmental Modeling Center at the University of North Carolina-Asheville and author of the city’s risk assessment plan.

“There Will Be Consequences”

The extremes of nature aren’t the only challenges facing Asheville’s future, and they may not be the most serious ones.

“The broader question is whether Asheville’s growing reputation as a ‘safe city’ will trigger growth that might threaten its essence [because of] new development, traffic and all the pressures attendant to growth,” said Spivey, head of The Collider.

Shuford, the former city planner, says that as more people settle in the area “there will be consequences.”

Among the challenges: “Land is limited, so how do we make use of it? How do we accommodate growth? Do we even want to accommodate growth?”

And perhaps most sensitive are the still unanswered questions that caused him to sweat 12 years ago: “What do we do with the people whom we need to provide with services but they can no longer afford to live in this community? There are lots of really big issues that affect the real estate industry, local government and even people’s lifestyle decisions.”

The influx of newcomers will further distort the existing imbalance between Asheville’s well-to-do haves and its struggling have-nots, he and other say.

Most of the newcomers bring financial resources enabling them to build and purchase homes, and to pay the higher taxes necessary for government to build storm-resistant roads, drainage systems and other infrastructure necessary to defend against climate-induced threats.

But, Shuford asks, where does that leave residents who may be displaced?

Even experts can only guess at how people and policy makers will respond.

“We’re in the heart of an early movement,” said Teague, the Biltmore Farms developer, “although the size of the movement is yet to be determined.”