Postindustrial’s newest columnist follows up her recent examination of art by the incarcerated with a journey overseas to Venice, where she was similarly struck by an art exhibit held inside a women’s prison.

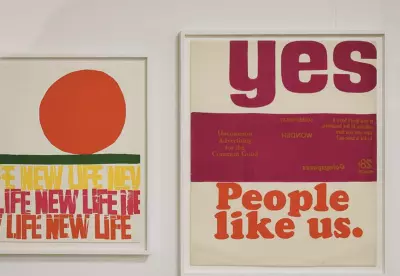

The theme of this year’s 60th International Venice Biennale Art Exhibition is Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere, and the curator Adriano Pedrosa followed through on that sentiment.

Image courtesy of Tamara White

Not only are creations displayed by international artists throughout the Arsanale, a complex of former shipyards and armories, and the Giardini di Castello, the largest green space in Venice, but this year also included the Casa di Detenzione Femminile, Venice’s women’s prison located on the island of Guidecca, a short boat ride adjacent to Venice.

This year, The Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church, presented its eleventh Biennale exhibition within the closed-off space.

Curated by Chiara Paris and Bruno Racinehe, the exhibition title, Con i miei occhi (With my eyes), is taken from a fragment of poetry that echoes an ancient sacred text and an Elizabethan poem. “I do not love thee with mine eyes” (Shakespeare, Sonnet 141) and resonates with 42:5 of the Book of Job: “Now mine eye seeth thee.”

As I walked through the space, the latter reference felt more relevant. I was seeing “thee.” I was seeing the bricks and bars and felt the invasive gazes of those locked away behind an unassuming wall along a stunning Venetian canal. Yet, the counterargument is that the women inhabiting the prison live amongst art they would not otherwise see.

The waves and welcoming calls from the incarcerated women hanging out in the exterior yard allude to their acceptance of the exhibition’s rotation of new faces as the monotony of another day is interrupted by the tours.

The exhibition also presents the prisoners with an opportunity to be contributors to the experience as tour guides and active participants in the editorial process by contributing to the Vatican City State’s daily newspaper, L’Osservatore di Strada.

My tour group was a blend of couples, mainly from Europe, who could understand the Italian spoken by our guides.

So, being the only American and solo visitor, I took in different details of the surroundings as the curated tour became a lyrical backdrop to my observations. Having visited American prisons, I found myself taking inventory of the difference. The first reflection being the inclusion of the exhibition and the ease in which I was able to enter the prison with only a reservation and my passport information. I am uncertain of the possible background checks that were involved prior to my arrival.

Additionally, I noticed that the women who greeted us in the outside spaces were not in prison uniforms but instead wearing what appeared to be their own clothing. With a children’s play area in the background, one might think that we were simply touring an urban art space rather than a centuries-old prison that was once a monastery, then a hospice for prostitutes, before transitioning to its current use in 1859.

There were patches of grass to enjoy, along with a large tree shading the benches. I noted the absence of barbed wire topping the perimeter walls. It almost felt serene despite the setting.

Unfortunately, a similar setting would never be considered for a similar exhibition in the United States. As the most punitive country in the world, the U.S. far outranks the rest of the world for the number of prisoners held behind bars. And female inmates in America number 127 per 100,000, whereas in Italy, it’s a mere 7 per 100,000 people.

Yet, presenting beautiful work within prison walls allows for a level of humanization rarely provided within a prison setting and lends to a rehabilitative quality.

As noted by writer and prisoner advocate Katrina Ray-Saulis, “Too often in our society we dehumanize incarcerated people, we lack compassion towards them, which serves only to perpetuate the very behaviors that got them arrested, to begin with.”

The trust the Vatican and Giudecca prison officials placed in the incarcerated community was moving. In my work with incarcerated American individuals, I am frequently heartbroken by the dehumanization and loss of empathy and understanding that exist within the carceral system. Seeing the exhibition in Venice provides a source of hope that one day, the United States, in its current efforts for restorative justice, will follow suit.