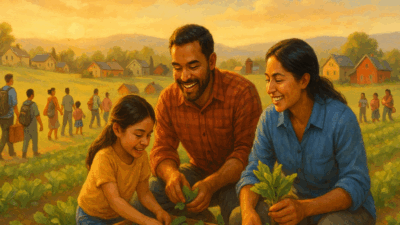

You couldn’t say Engilcheck’s old mines helped grow the economy. As part of the USSR, that wasn’t the aim, but for the people who lived there — like their stateside counterparts — life revolved around the industry.

While mining communities in the U.S. declined when that superpower started using more cheap foreign imports and labor, in Engilcheck it was the fall of the USSR that spelled the end for this community in a remote part of Kyrgyzstan, near the Chinese border. Today, only a handful of families remain, earning a living as herders or park rangers, still hoping that their town can be revitalized.

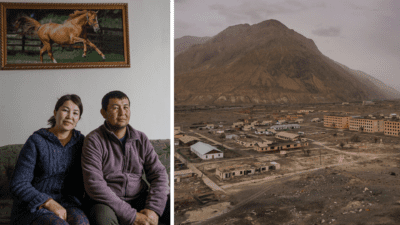

“There were 5,000 people living here when the mines were open,” said Ulan Asanbaeva, 32, who lives in the town with his wife, Nellie, and their two young boys.

After the USSR collapsed in 1991, he said, the Russian workers left, the mines were closed, and people gradually moved away. Now, only about 30 families are left.

After gaining independence in 1991, Kyrgyzstan floundered economically. The collapse of the Soviet system “led to the virtual paralysis of industrial production in the country, including the mining industry,” said a 2002 report commissioned by the International Institute for Environment and Development. “This resulted in social and economic decline.”

Ulan was born in Engilcheck but left with his family in 1995, relocating to the nearest large town, Karakol, 82 miles away.

“I didn’t like living here at first, but after a while, I grew to love it,” he said. “The main reason is it’s quiet, and we can save money because it’s very cheap to live here.”

Kyrgyzstan did subsequently develop some mining projects, the main one being the Kumtor gold mine that opened in 1996. Today, it’s the largest gold producer in the republic, producing 10 to 23 metric tons of gold per year, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. Unfortunately for Ulan’s family, Engilcheck’s tin mines were left to rot, and so the family decided to return to the ancient ways of their people: herding.

But the 100-year thunderstorm of Soviet collectivization had eroded traditions and washed away old migration pathways.

For the Kyrgyz people, the disbanding of the communist collectives caused an economic crisis that “left large numbers of semi-nomadic herders operating as individual family units, rather than as part of a larger collective or clan unit, for the first time in their history,” John D. Farrington wrote in a 2005 article published in Nomadic People’s Journal.

Worse still, the Soviets had over-grazed the land, and there wasn’t enough pasture to go around.

As Ulan put it, “Life was too difficult in Karakol because there were too many animals, so I decided to return [to Engilcheck] to continue my people’s traditions.” Today, he has viable herds of sheep, cows, and horses, plus a few yaks.

His wife, Nellie, teaches Russian and English at the town school housed in the old kindergarten. Outside, a rusty playground provides the only dashes of color in the dead, brown-and-yellow townscape. The nearby high school is one of the largest derelict buildings, with a rotting basketball court outside, bearded by shrubs.

Nellie said the town’s 27 children attend school for three hours a day through grade five, when they go to Karakol for high school — often living with relatives. “We moved here four years ago,” she said. “I didn’t like living here at first, but after a while, I grew to love it. The main reason is it’s quiet, and we can save money because it’s very cheap to live here.”

The road to Karakol is in OK shape, but it helps to have a four-wheel-drive vehicle or a very strong stomach.

Most importantly, it’s kept clear of snow during the winter by a team of workers who must be among the toughest contractors in the world, living among their bulldozers atop a 4,000-meter-high pass.

Engilcheck, which is named after a local species of moss or lichen, encrusts the base of a valley near the Khan-Tengri National Park. It’s within a 50-km buffer zone on the Chinese border, and foreigners need a government permit to travel there. Visit Karakol, a local tour company, has started offering tours of the ghost town and, starting this year, has taken seven groups. Ulan and Nellie see tourists as key to keeping the town alive and have offered their cozy home as lodging. “It would be really great if the government canceled the permit system and we received more tourists,” Ulan said.

Nellie agreed. “I have friends around the world now,” she said. “We met people from America, and our visitors from the Netherlands promised to come back. They loved it so much.”

Ulan said he isn’t worried about a sudden influx of travelers: “I wouldn’t care if a lot of people came here, as it would raise up our country and help with development. As long as the tourists are polite … I would always welcome them.”

9