Celeste Malvar-Stewart’s first encounter with Gandalf, a gentle giant of a sheep, was with his fiber.

Newly relocated to Columbus from New York City, the sustainable fashion and textiles artist was looking for new material to work with and, if possible, a fashion community. She found both.

Wool from Gandalf, an American Lincoln longwool, became part of a collection Malvar-Stewart created for the Aveda Institute in 2016. He’s now such a favorite — his serene personality and his fiber — that she incorporates at least one of his locks into each couture wedding gown she makes.

Like the Postindustrial communities they call home, Malvar-Stewart and other designers have become experts of reinvention, some of them leaning more deeply over the past year into reuse and sustainability as an avenue to heal — themselves, the planet, and others.

“Especially with the tragedy of the pandemic, it’s given us time to think about where we want to put our money, whether we can really afford to buy fast fashion,” she said. “We also want to connect. I’m giving more workshops than ever. People are interested in knowing the animals. Even if it’s a pair of socks, when it comes from a sheep named Sugar, you just care more.

“Fashion has always been that superficial part of society, but I think we’re realizing it doesn’t have to be.”

Her non-seasonal line of clothing and accessories, MALVAR = STEWART, uses only salvaged vintage fabrics, wool from local farmers, and natural dyes. Her newest collection debuts this fall and evokes tension, joy and a sense of ethereal beauty as an expression of emotionally dynamic times, she said.

“As an artist, I think we’ve realized again in this pandemic that art can be healing, regenerating,” she added. “Art can be a response to grieving.”

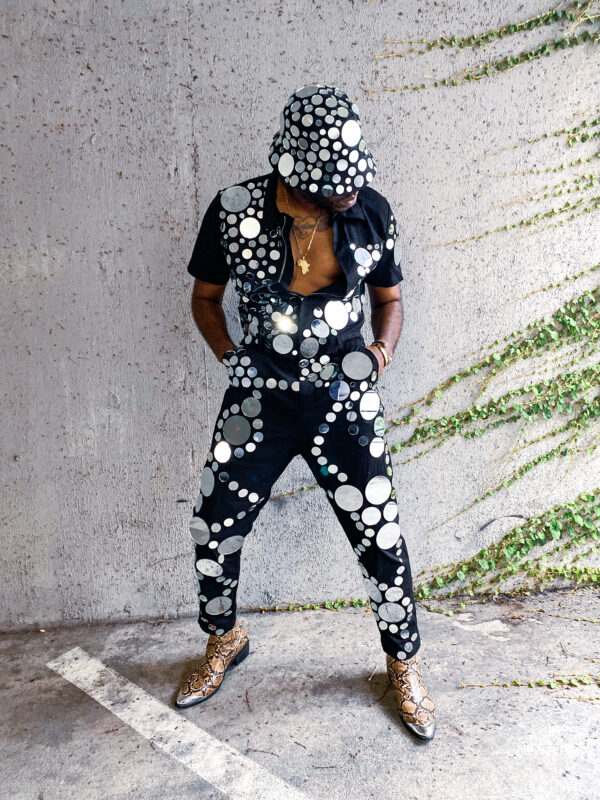

Birmingham designer Daniel Grier sees an emotional connection between his repurposed denim and the ways he once was looking to reimagine himself.

He’d started his career studying nursing and then switched to community health education because a cousin, who was also a close friend, was lost to AIDS. When Grier was diagnosed eight years ago with HIV, it took a journey into fashion and art — and a newly discovered passion for tie-dying jeans he loved too much to discard — for him to return to encouraging HIV awareness and eventually sharing his own story.

“I wanted to start building something that would make me proud,” he said. “I wanted to combine fashion, art, and activism. HIV awareness was part of the mission from day one.”

After a robust response to his jeans on social media, Splashed by DKG emerged.

His first runway collection debuted in 2014 at Alabama International Fashion Week. He co-founded Magic City Fashion Week in 2017 to cultivate and connect Birmingham’s art and fashion communities, and he now splits his time between Birmingham, where his business is based, and clients he works with in Atlanta.

Grier’s Freedom Collection, conceived during the pandemic shutdown, stemmed from bins of jeans he’d kept, some from as far back as 10th grade.

“That collection was entirely made of repurposed materials,” he said. “Freedom was allowing myself to do whatever I want. I took them all, sat down, washed them, and cut them into squares. I wanted them to take on a whole new look without having tie-dye. When I’m working, I’m always envisioning dressing superheroes. I want people to feel great; I also want to go up a notch. I want to give you your cape.”

That’s the way Grier has been channeling his voice since that first pair of jeans in 2013.

“That’s exactly what I did with the absolute worst news of my life,” he said. “I didn’t throw the old jeans away; I reinvented them.”

In Nashville, giving clothes a new story, or a second story, is central to the mission of Rank & Sugar, a vintage label by designer Suzanne Wade, who embroiders and updates military pants, jackets, patches, and other pieces.

Her journey started with an M51 jacket from World War II that she turned to during a difficult transition.

“I was going through a lot of change and upheaval, and I had this vintage jacket that just felt so safe and amazing and somehow, in a way, even empowering,” she said. “I felt I needed to express myself with words in it. These phrases I would embroider were sort of mantras for myself, and it just resonated with people. Then I expanded to Vietnam-era utility shirts and pants.”

When someone from J.Crew reached out, hoping to collaborate with her for New York Fashion Week, it was the nod she needed to go all in. She’s now found a home among the fashion-forward in Nashville, where she sells her work online and in boutiques.

Wade adds her touch to custom orders for people reaching out with family heirlooms.

“The only word that comes to mind is ‘sacred,’” she said. “I’m honored that people trust me with these pieces. They carry so much energy. I try to infuse as much love and peace as possible before I send them back out into the world.

“I really try to be sensitive, too, to the original purpose. They protected soldiers; they have these storied pasts. I want to give them a new life, but at the same time, I love this notion of protecting women in their new life, giving them a sense of empowerment and a voice.”

Her labels are Army name tape, made in the same place as U.S. soldiers’, and all of her Army patches are Army-issue, found at flea markets or on eBay. Authenticity is important to her. So are reuse and sustainability.

“Storytelling is something people are craving more. These pieces have a story and a past. There’s a way to connect with that and continue the story, and it prompts the telling of your own story.”

In Pittsburgh, fashion designer Tereneh Idia blends many of those elements — authenticity, sustainability and human connections — in her global eco-design collaboration, IdiaDega, which offers a platform to co-design, co-create, and revenue-share among IdiaDega, the Olorgesailie Maasai Women Artisans of Kenya , and the Beading Wolves of the Oneida Indian Nation.

She started the collaboration by launching OMWA in 2013, incorporating Indigenous adornment in sustainable textile arts and design and exhibiting in Paris, New York City, Nairobi, and Pittsburgh. In 2016, they expanded the collaboration to include the Beading Wolves, an Oneida family of artisans.

“The connections between me as a Black American, the Maasai, and Native Americans are at the core of this collaboration,” she said. Their co-designed work, sold online and in pop-up shops and boutiques around Pittsburgh, marry contributions by all three sources, sometimes in a single piece.

Her aim is to not only use sustainable materials, but also to sustain the human connection by honoring women and cultures that big labels often borrow from without crediting or compensating.

“Fast fashion is harmful to the environment as well as to the people working there,” she said. “Sustainability really does include the economics.” The collaboration offers a design stipend, pay for research and development work and selected samples, and then a portion of sales.

Idia, whose individual designs embrace a “global minimalist” aesthetic, works hard to be clear that this is not charity.

“It is creative collaboration, sustainable for each other and the planet,” she said. “It’s about how we maintain and how we celebrate who we are and what we are contributing. All too often, African American women, African women, Indigenous women, women of the global South, and women of the global majority really are the ones who are the innovators.

“They’ve invented a style of design, but they don’t always get the credit for the work they do. I think that’s something that needs to change.”