GLASGOW — Thirteen-year-old neighbors Alex Williamson and Mary Hart worked in a factory here more than 150 years ago. They married at 23 and had a family. Moved to America. Their kids had kids. And so on, so on, and so forth — until you get to me.

Alex and Mary, my great-great-great grandparents, were just two of the thousands who labored in factories, mines, and shipyards during the Industrial Revolution in Scotland. When the couple moved their family to a Central Pennsylvania coal town in the early 1870s, the Glasgow they left behind was overcrowded, polluted, and growing at a furious pace.

But the city that once built ships now builds satellites. The city that once extracted coal now explores using warm water from abandoned mines as a heat source. It’s a city with a legacy of empire, racism, and inequities looking to create a more forward-thinking, inclusive, and socially just atmosphere.

No single, simple narrative

Glasgow city proper was home to 635,000 people in 2020, about the same as the 2020 population of Detroit. Situated along the River Clyde in the Scottish Lowlands, it’s Scotland’s largest city, though Edinburgh — about a 90-minute drive east — is the capital.

Glasgow’s contrasting and sometimes conflicting personalities illustrate the difficulties of putting the city’s past into context. These personalities also influence movements and policies meant to move into a sustainable future without leaving groups of citizens behind.

“There’s a lasting legacy of the city as dangerous,” says Jamie Cooke, head of the Royal Society for Arts, Manufactures and Commerce Scotland. “It’s one of those cities — like a lot of gritty, postindustrial communities — that in the U.K. is still seen as a ‘hard’ city.

“The ‘Glasgow Hard Man’ is seen as a kind of threatening caricature at the same time as Glasgow’s regularly being voted in the top 10 destinations in Conde Nast as one of the most glamorous cities and places to go.”

This grit-versus-glam story is only the surface view of Glasgow. Cooke says it’s “an interesting balancing act for Glaswegians — how much do they feel ownership of that and how much do they still feel disconnected?”

Connecting through inclusion

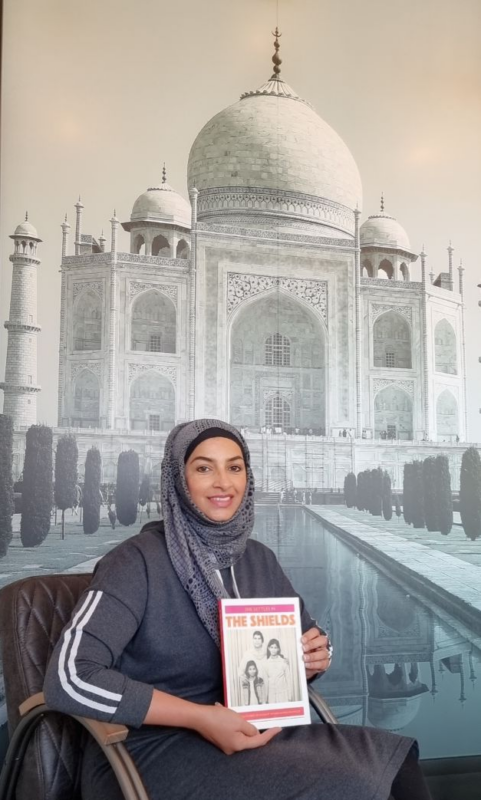

Syma Ahmed, development officer for the Glasgow Women’s Library Black & Minority Ethnic (BME) Women’s Project, says equity for historically marginalized groups is vital to making Glasgow a place where people want to live and work.

Organizations around the city have realized this, she says, and as they scrutinize their policies, demand for the library’s diversity and inclusion training program grows.

“What are these spaces offering, and is it inclusive? And if not, what needs to be done? We need to have these conversations,” Ahmed says.

Creating inclusive historical narratives made news in 2020 when The Hunterian, Scotland’s oldest museum, appointed Zandra Yeaman to a newly created position — curator of discomfort.

The museum, opened in 1807 at the University of Glasgow, charges Yeaman with challenging its representation of subjects including race and gender, adding context that the exhibits historically excluded.

For example, Yeaman points out the Blackstone Chair. The museum description explains that students sat on the stone for oral graduation exams from the university’s 1451 founding until the mid-1800s.

“There’s nothing inaccurate about that. But wouldn’t it be even more interesting to know that the very first African American doctor sat on this chair for his exam?” she says, referring to James McCune Smith, who graduated in 1837 with a medical doctorate. “And wouldn’t it be interesting to know that no woman ever sat in this chair?”

Yeaman says education is just a first step.

“The goal is to shift practices, to shift thinking,” she says.

A proud tale of industry, reimagined

Understanding and internalizing history is key to building a sustainable, environmentally safe, and economically stable future, say those working toward those goals.

“We all are acutely aware and proud of our industrial heritage, but it does have some negative connotations,” says Jennifer Griffith of EGG Lighting.

The company remanufactures lighting equipment, essentially repairing and upgrading components to operate like new, rather than replacing and disposing of old units.

“Manufacturing into the 21st century needs to be clean,” she says. “It needs to be hitting that core identity and giving Glasgow something to be proud of again, but not with the past mistakes that we’ve made in producing more pollution and making the world dirtier.”

EGG Lighting is part of the Circular Glasgow Network, a Glasgow Chamber of Commerce initiative where sustainability-minded companies share ideas.

Alison McRae, senior director of the Glasgow Chamber of Commerce, says circular economy practices — where the goal is to waste nothing throughout the manufacturing or service process — are vital to combatting the climate crisis. They’re also a way to help Glasgow achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2030 — a goal 15 years ahead of the United Kingdom’s as a whole.

It’s also a robust business model, she says, because it helps companies build a reputation that attracts customers, clients, and workers whose ethics align with their own. It also makes room for creativity and innovation that can be lacking in traditional, linear processes.

Circular Glasgow Network member ACS Clothing, located in the Glasgow suburbs, extends its reach by regularly collaborating with schools such as Glasgow Caledonian University. Students there spend time touring ACS’ facility, which stores and cleans rental clothing and fulfills orders as part of its mission of promoting sustainable fashion. Master’s level logistics students learned about ACS practices such as collecting rainwater from the roof to wash clothes and filtering the “sludge” from laundry into drums to be sent off and transformed into building materials.

Reusing and reimagining the relics of an industrial past are also vital to designing a city that can make progress well into the 21st century, says Duncan Booker, chief resilience officer for Glasgow City Council.

He cites the ongoing Clyde Gateway development in the city’s Dalmarnock neighborhood as an example.

“The East End of Glasgow was one of the most heavily industrialized parts of Europe at one point,” he says, and to use it, “we had to remediate contaminated land with thousands of tons of earth, basically sifted for heavy metals like cadmium and the mercury from previous industrial use.”

The development — a mixture of offices, housing, and light industrial spaces — is being built on sustainable principles, addressing issues such as stormwater management and alternative energy, including geothermal, Booker says. Though still in investigative phases with the British Geological Survey, there is the promising prospect of harnessing energy from warm water in abandoned coal mines to heat homes and businesses in a more sustainable, affordable way.

Shared global narrative

Though all cities have their singular histories and problems, Glasgow’s challenges mirror many in the postindustrial regions of the United States.

The city is trading ideas with others worldwide through groups such as the Urban Transitions Alliance, which includes Baltimore, Buffalo, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and cities in China and Europe. In 2021, Glasgow and Pittsburgh formalized a Sister Cities relationship to address issues including health equity, climate change, and racial justice.

“That kind of global thinking of cities and regions now is important,” says Glasgow city councillor Ruairi Kelly. “Some (cities) are a couple years ahead of us: What have the issues been? What have they encountered? How have they dealt with it? And what unique solutions can we come up with that pertain to Glasgow? All of our cities would be different, but you need to have those conversations and learn from other people.”

The city would be one my great-great-great grandparents wouldn’t recognize. Every person I meet and every person I talk to here leads me to more stories and more facets of the city’s personality than I’d have time to explore in a year. I wonder now if modern Glasgow is a place Alex and Mary might never have left.