Jamie Wells doesn’t want to vote ever again.

The one and only time she did was back in November 2020. That single ballot caused so much stress and turmoil and mounting debt that she will probably never again do it..

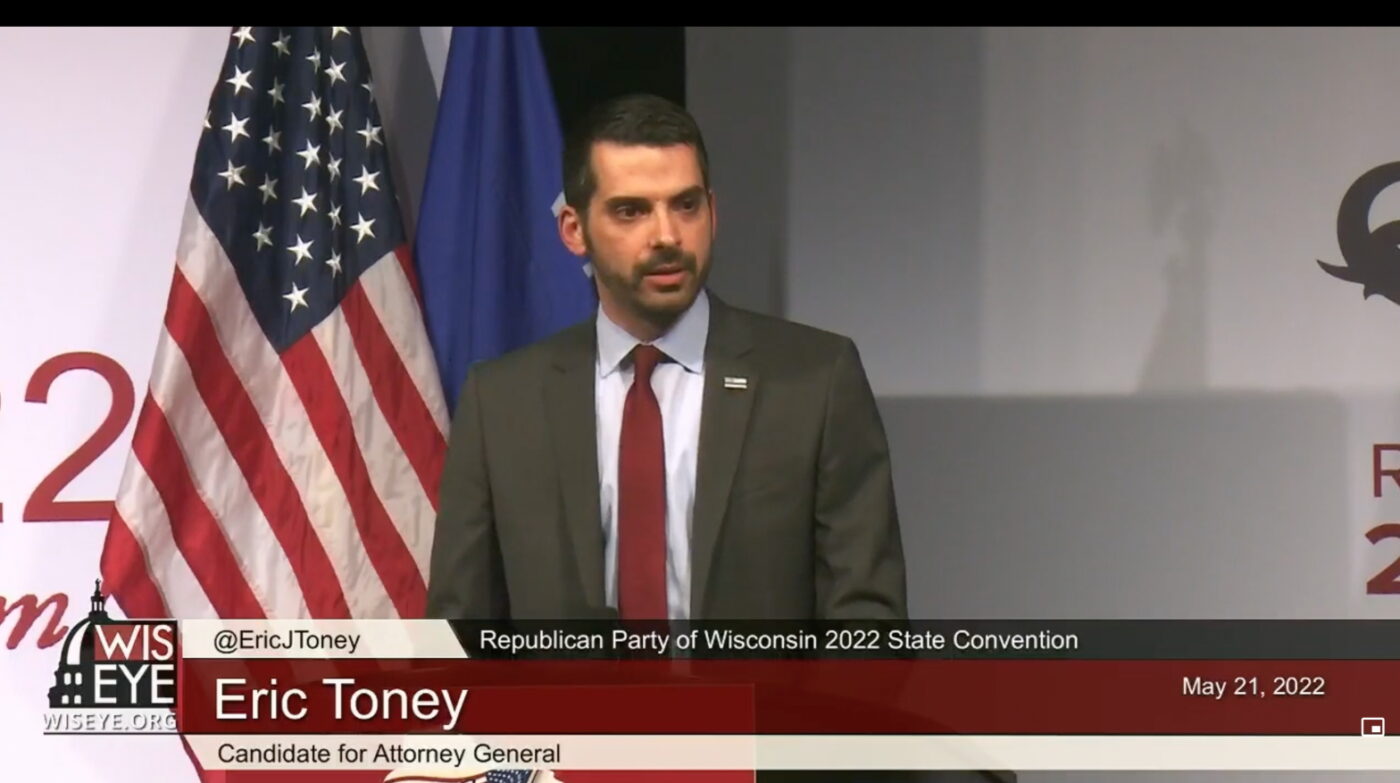

Wells, 53, is one of five people charged with election fraud for having a UPS Store listed as their voting address by Fond du Lac County District Attorney Eric Toney — a Republican candidate vying for Wisconsin attorney general who has made voter fraud and election security key issues in his campaign.

Wells and her husband, who was also charged, could be considered collateral damage of the widespread false belief that massive voter fraud marred the 2020 election. This lie has sparked numerous lawsuits in Wisconsin and a raft of GOP-authored bills seeking to impose voting restrictions — all of them vetoed by Democratic Gov. Tony Evers.

Under Wisconsin law, only residential addresses — where someone actually lives — can be used for voter registration.

Wells said she and her husband didn’t know using a UPS Store address to vote was a problem. She said she felt motivated to vote for the very first time to re-elect then-President Donald Trump.

The couple now faces up to three and a half years in prison and maximum fines of $10,000 each. Wells and her husband also would be barred from voting until they serve their full sentences, including any probation or supervision.

A Wisconsin Watch analysis of the state’s voter rolls found that Wells and the others charged in Fond du Lac County are far from the only people who could unknowingly have listed incorrect voting addresses.

There are 30 UPS Stores in the state, and 117 people have those addresses on their voter registrations. Additionally, a Wisconsin Watch search of 47 U.S. Post Office addresses in Dane and Milwaukee counties, where people can get a P.O. Box, found 44 voters registered at those addresses.

Wells said she and her husband have used that UPS Store in Fond du Lac as their address for decades without a problem. They registered to vote using that address because they didn’t have another one to list.

“But this (prosecutor) here seems to think I’m a criminal,” she said. “And that’s the part that upsets me most of anything.”

Wisconsin Watch found at least one district attorney in Wisconsin who received a similar referral of people using UPS Store addresses to vote. La Crosse County District Attorney Tim Gruenke said he was alerted to 15 people who had voted using these addresses in 2020 by the La Crosse city clerk. Gruenke, a Democrat, declined to prosecute.

“I’m not sure what kind of fraud would be happening,” he said.

Ion Meyn, an assistant law professor at the University of Wisconsin, called the cases against Wells and others in Fond du Lac County “a real abuse of (prosecutorial) discretion.”

Toney did not respond to multiple requests for an interview or answer emailed questions. But in a statement to Wisconsin Watch, he said attorney ethics rules prevent him from commenting on a pending case.

“Elections are cornerstone (sic) of our democracy which must be defended at every turn, not just when you agree with the law or the politics,” he wrote. “I want people (to) exercise their right to vote and ensure they do so lawfully. Wisconsin law requires someone to register to vote where they live, not where they receive mail. That is made clear on voter registration forms.”

Toney touts tough-on-fraud stance

Voter fraud is extremely rare because, among other factors, it’s difficult to do with all of the safeguards and checks in the process. Multiple reviews and audits found no widespread fraud in Wisconsin’s 2020 election — or in any other state.

Local elections clerks in Wisconsin referred 12 cases to prosecutors related to the 2020 general election, out of 3.3 million ballots cast. Wells and the others charged in Fond du Lac County were not among them.

Toney has said the tip came from Peter Bernegger, a Wisconsin man who has since been fined $2,400 by the Wisconsin Elections Commission for making “frivolous complaints” — including the one against Wells.

Despite that, claims of voter fraud remain ubiquitous, both in Wisconsin and across the country.

Election and criminal law experts questioned the motives behind, and the validity of, the cases against Wells and others. They say prosecutions like these — as well as disinformation about voter fraud and its prevalence — can discourage people from voting and lead to new laws that add unnecessary barriers to voting.

“On a prosecution where the level of wrongdoing doesn’t necessarily amount to a kind of criminal enterprise — and yet felony sanctions are what’s on the table — that sends a message that our political system may not care about fair access and balancing the interest in access and the interest in security,” Marquette University election law expert Atiba Ellis said.

“If a voter can’t trust that an innocent error won’t result in a felony conviction, that might make voters think twice about whether it’s worth it to vote at all.”

During a February news conference, Toney said there was a public education aspect to his decision to charge.

“It’s important to draw attention to this so people understand how do they vote or register, to make sure that they don’t end up with a referral to a local district attorney that could result in a felony voter fraud charge,” Toney said.

In April, Toney also asked Evers to remove five members of the Wisconsin Elections Commission related to voting in nursing homes during elections in 2020. Toney said he would criminally charge the commissioners if he had jurisdiction.

And during his introduction at the Republican Party of Wisconsin convention in May, Toney pushed his reputation as “one of the most aggressive prosecutors of election fraud” in the state.

“We’ve earned the right to have an attorney general that will stand up for us, enforce the rule of law, lock up dangerous criminals and protect the integrity of our elections,” he said. “That is my track record as a district attorney.”

Couple leads mobile life

Wells considers Fond du Lac home, although her Louisiana accent might hint otherwise.

Wells met her husband when he was working in Louisiana, and they married in 1989. A month later they moved to Madison. His work on farms takes him all over the state. Instead of being separated for long periods of time or long drives, they live in a 42-foot pull behind camper.

It has three slide outs, a washer and dryer and feels just like a small apartment, she said.

They eventually found themselves spending more and more time in Fond du Lac, so they dropped their P.O. Box in Madison for a mailbox they’ve had for about 30 years.

Wells’ story is a near-perfect description of how election law experts say incorrect votes from eligible voters can happen.

In an interview with Wisconsin Watch, Wells said while she considers herself a Republican, she and her husband had never been politically active. She didn’t even know Wisconsin was a swing state — but Wells wanted to help President Trump get re-elected.

“I just figured Trump could do a better job,” she said. “And I just ain’t a Joe Biden fan. He seems like he might be a nice guy, but I just thought Trump was the better thought.”

So she and her husband registered to vote online. When it came time to enter their address, they put the same one they’ve used for decades.

“It never told me nothing (was wrong),” she said. “They gave us the voter registration. Sent our ballots. We sent them back in, and that was it.”

Police, reporter come calling

Then in January, while she was visiting family in Louisiana, Wells got a call from a Fond du Lac police detective.

“I didn’t think it was real,” she said, citing an increase in political calls around that time. “… He might have said he was a detective. I don’t want to lie if he did or didn’t. … And I spoke to him, and I told him the exact truth of what happened.”

That was the first indication that something might not have been right with her vote. But weeks went by and there wasn’t a follow up call or anything in the mail.

Then she started to get other calls she wasn’t sure about. Then came the texts and emails and voicemail messages left with family members for her. They were from a New York Times reporter.

She mentioned it all to a friend, who then looked Wells up in Wisconsin’s online court record system. It showed Wells was facing a charge of falsely procuring a voter registration.

“My friend calls me … and she said, ‘I have something to send you. Do you want me to send it to you or your daughter? It might upset you.’ I said, ‘No, go ahead and send it to me.’

“And that’s when I found out I was being charged.”

‘A hammer in search of a nail’

Election law experts are quick to differentiate between voter fraud — which is exceptionally rare — and voting errors.

In true voter fraud, a voter or group or people scheme to knowingly violate election law to get a vote cast that would otherwise not have been allowed. But incorrectly cast ballots come from eligible voters who mistakenly vote or register in the wrong way.

Eliza Sweren-Becker, voting rights and elections expert in the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice, said when there are instances of misconduct, it’s usually fraud targeting voters — not the other way around.

Ellis, the Marquette expert, agreed, pointing to a recent election fraud scandal in North Carolina.

In that case, a political operative intercepted blank absentee ballots and “unlawfully, willfully, and feloniously” submitted them, concealing that they were not sent by voters, state prosecutors alleged. The fraud occurred in the state’s 2016 general election and a 2018 primary for a seat in Congress.

During the 2018 race, the Republican candidate won by just 905 votes, the Raleigh News & Observer reported. The State Board of Elections refused to certify the results after questions emerged about an alleged ballot-harvesting scheme and later called for a new election. The winning candidate did not run in that election. The operative died earlier this year while awaiting trial.

That’s what an illegal voting operation looks like, Ellis said — not an innocent mistake by a person who is actually eligible to vote.

Ellis said the choice to prosecute cases involving incorrect votes suggests an effort not to ensure the integrity of elections but to promote a false narrative that there is widespread criminality in the voting process.

“Fraud is about an intent to deceive,” Ellis said. “And the danger in our current election integrity rhetoric is innocent mistakes get swept up and purported as deceptive acts.”

This rhetoric can be used to justify more restrictive voting laws, Sweren-Becker said. These laws tend to have a bigger impact on racial minorities, the poor and others vulnerable to exploitation, Ellis said.

The lie of widespread fraud has consequences: Two-thirds of Wisconsin Republicans told a June Marquette University Law School poll that they have little or no confidence in the legitimacy of President Joe Biden’s election.

However, Sweren-Becker said organized efforts to find voter fraud have mostly come up empty because it’s not widespread and rarely impacts elections.

The new laws and prosecutions are all “a hammer in search of a nail,” she said.

Wells doesn’t want to vote again

The months since Wells was charged have been tough on her, her family and even her marriage.

“I’m not a depressed person, you know, I’m usually a happy-go-lucky person,” she said. “(Now) just kind of my emotions run like a roller coaster. I find myself crying, and I’m not a crier. Don’t cry a lot.”

She worries about what people think of her now that she has been charged as a felon. And the publicity around the case has taken away her privacy.

Despite her experience, Wells does believe there was cheating in Wisconsin’s 2020 presidential election. According to the criminal complaint, she told the detective he should be investigating the election, because “they took it away from Trump.”

In March, the Wisconsin Elections Commission dismissed Bernegger’s complaint against Wells but sent a letter urging her to double check her voter registration. As of June 26, the registration remained active and unchanged.

A couple months ago, as she tried to set up a business credit card for her husband, she entered the address at the UPS Store.

Unlike the state’s voter registration system, the credit card company flagged the address and said she couldn’t use it.

DA refuses to prosecute ‘mistakes’

Toney wasn’t the only county prosecutor who had to decide whether to charge voters with a UPS Store address on their registration.

Gruenke, the La Crosse County district attorney, said he reviewed 22 cases referred to his office after the November 2020 election for people who used UPS Store addresses to register, including 15 who voted.

Gruenke gets a handful of referrals for suspected election fraud after major elections. He said he’s charged maybe five people in the past decade, but most referrals involve a simple mistake.

Sometimes someone requests an absentee ballot but then votes in person. Elderly voters who have memory issues may vote at the wrong polling location. Sometimes there’s a mixup due to a common name, like a father and son who are Sr. and Jr.

But Gruenke has charged some cases, including a man who falsely listed a vacant lot as his voting address and a person who was on probation and ineligible to vote.

He said violating the law requires intent, and that’s why he didn’t charge any voters who appeared to have made honest mistakes when listing their addresses. In those cases, his office investigated and found that some people were traveling or living out of state part-time. Gruenke mentioned one person who was moving and didn’t know where they’d be living at the time at the election.

The voters had registered online using the address on their driver’s license. They included their phone numbers — and many appeared to be married couples.

“There’s no way a jury would say they intentionally did something to fool anybody,” Gruenke said. “…You can be careful all you want and still make a mistake.”

‘A really tortured view’ of the law

Meyn, the UW law professor, said for a jury to convict Wells and the others, Toney would need to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that they weren’t eligible to vote — and that they registered knowing they were not qualified to vote.

Nothing in the criminal complaint alleges they were ineligible or knowingly misrepresented where they lived.

Meyn called it “saddening” and “abhorrent” that Toney is subjecting Wells and the others to criminal prosecutions and public humiliation.

“Here you have a prosecutor who is taking a really tortured view, in my mind, of what this provision (in the statute) means,” he said. “I just find that so irresponsible.

“It’s obviously for political reasons and it’s really disappointing.”

Wells and her attorney plan to fight the charge. They are optimistic they’ll win. But even if they do, the episode has already exacted a high cost.

The couple expects to rack up more than $17,000 in legal bills. Wells said relatives have pitched in to pay for their defense.

“We’re not millionaires, so we’ve had to borrow money,” she said. “… And yeah, (we) still have to pay it all back.”

Wisconsin Watch is a nonprofit newsroom that focuses on government integrity and quality of life issues.

Matt Mencarini joined the Center in 2022 as an investigative reporter covering voting rights and threats to democracy. Previously, he worked as an investigative reporter for the Louisville Courier Journal where he was part of the team that won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for breaking news for coverage of hundreds of last-minute pardons and commutations by an outgoing governor. He and a colleague revealed a racial disparity in who received commutations for drug offenses. Before that, he worked at the State Journal in Lansing, Michigan, as well as newspapers in Illinois and Florida.