America spends billions of dollars every year to warehouse inmates, some of whom spend their time behind bars creating art that expresses their troubled pasts and serves as a remedy for the creative incarcerated.

America the Great, so the saying goes, leads in many areas. Some good, some not so impressive.

One area where the United States is out front in staggering numbers is its rate of incarceration. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, the United States is currently spending over $80 billion to house the 1.8 million individuals who are behind bars. Another $2.9 billion is spent by families on phone calls and commissary purchases. And states spend upward of $9.3 billion each year incarcerating individuals for parole or probation violations.

In contrast to the billions spent on incarceration, the annual global art market is valued at $59 billion, yet few incarcerated artists receive the recognition they deserve. Validating these artists can enhance their self-worth and introduce art collectors to new perspectives and diverse narratives.

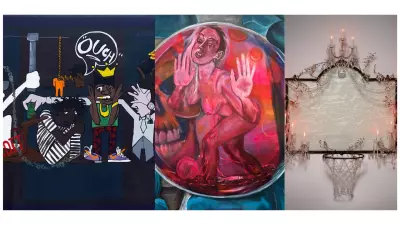

Prison art is increasingly entering the mainstream art world, earning prominent recognition through exhibitions like “Marking Time” at MOMA PS1 and “How Art Changed the Prison” at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Connecticut.

Ohio self-taught artist and filmmaker Aimee Wissman is a formerly incarcerated artist and co-founder of the Columbus, Ohio-based The Returning Artists Guild, an abolitionist-focused organization that supports directly impacted practicing artists across Ohio and beyond. Wissman’s work, including School to Prison, has been featured in the widely exhibited group show Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, curated by Nicole Fleetwood, and has been featured in numerous media outlets, including Smithsonian’s FOLKLIFE magazine. Wissman’s work is not sold nationally but is primarily featured in local exhibitions as a visual narrative of her journey.

In contrast, the American artist David Hammons uses his artwork to examine urban African American life through a politicized lens. His piece Untitled features a chandelier and basketball hoop, referencing “the fragility of a culture which places, as its highest pinnacle, the athletic performance of certain individuals”. Unlike regionally-sold art at accessible prices, Hammons art sold for $8 million in 2013.

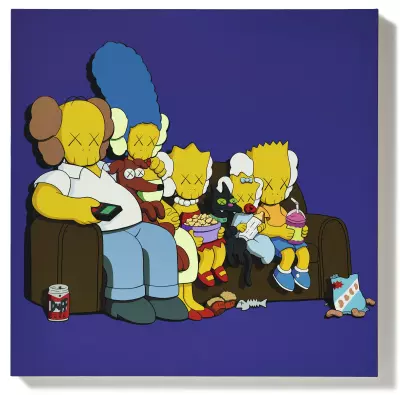

Another contrasting pair of artworks by the formerly incarcerated artist Kenneth Webb and the ubiquitous and world-renowned artist Brian Donnelly, known professionally as KAWS.

KAWS is a contemporary, million-dollar artist who began as a graffiti artist and has since become a fashion designer and collaborator on toys and furniture. His painting titled Untitled #3, a spin on the Simpsons, sold for $2.7 million.

Kenneth Webb was recently released from a California prison where he served more than fourteen years after being sentenced as a teenager. Webb says that he always thought of art as a gateway into containers of possibility. “When I reflect on how my artistic practice has served me throughout my time inside the industrial human warehouse we know as prisons– I find that, in many ways, the vehicle of self-expression has opened many portals–the most important being the portal of connection,” Webb said. He also believes that it’s an innate desire for a human to express that they exist inside space – to be known to connect the dots between form and blank space.

That connection and understanding is also the focus of the Ohio Reformatory for Women Portrait Project, intent on providing a different perspective on incarcerated women. The Ohio artist Kirsta Benedetti is painting portraits of the women to present them with value and dignity. According to Benedetti, “the minute somebody is painted, they are very important and seen as very valuable, so I have decided to be really conscious of who I paint.”

Hattie Gilbert for the Ohio Reformatory for Women

Portrait Project.

Another formerly incarcerated Ohio artist, Zeph Vondenhuevel, notes that “unleashing your creativity, through whatever medium it may be, is a transformative process. It has helped me heal parts of myself in ways that I never thought possible. Creating has helped me find community, and it has bolstered my advocacy. It has given me a purpose.”

Arts-based programming, both inside and outside of prison walls, is therapeutic and a powerful method for emotional self-regulation and higher-order thinking skills. Furthermore, life effectiveness skills such as learning from mistakes and self-reflection are associated with arts-based learning and the creative process which in turn has a direct impact on rehabilitation and rates of recidivism.

For Tyra Patterson, who was wrongly convicted as a teenager and spent twenty-three years in an Ohio prison, artwork is an avenue to reflect her life experiences. Warrior is Patterson’s most personal piece yet. “It’s about how my circumstances went from innocence to one of survival. I can’t help but look at the little girl in the photo and wonder what could’ve been. I think about the physical and mental remnants of every one of my fights. Even though broken glass can be put back together again, the cracks will never go away.”

The healing impact of artistic expression for those impacted by the carceral system, including emotional healing, an increase in understanding of oneself and others, the ability to develop a capacity for self-reflection, and reducing mental health symptoms, is clear. The lawyer, author, and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, Bryan Stevenson, astutely points out, “Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.”

Think about your life and journey, and then consider a past action that might have pushed the boundary of the law. Now, consider what that looks like visually. We each have our own landscape and visual story. What does yours look like?