Some folks celebrate Pride only in June.

But for Maigen Sullivan, that wasn’t enough. So she and Josh Burford decided to create an organization that catalogs and highlights the history of LGBTQ community in the Deep South called Invisible Histories.

Their origins in 2018 were modest, according to Sullivan.

“At the time, all we had was hope, nonprofit status, and about $1,500,” she told Postindustrial.

But how they’ve grown since then. Invisible Histories was recently awarded a $2.2 Million Grant from the Mellon Foundation to Save LGBTQ History in the Deep South.

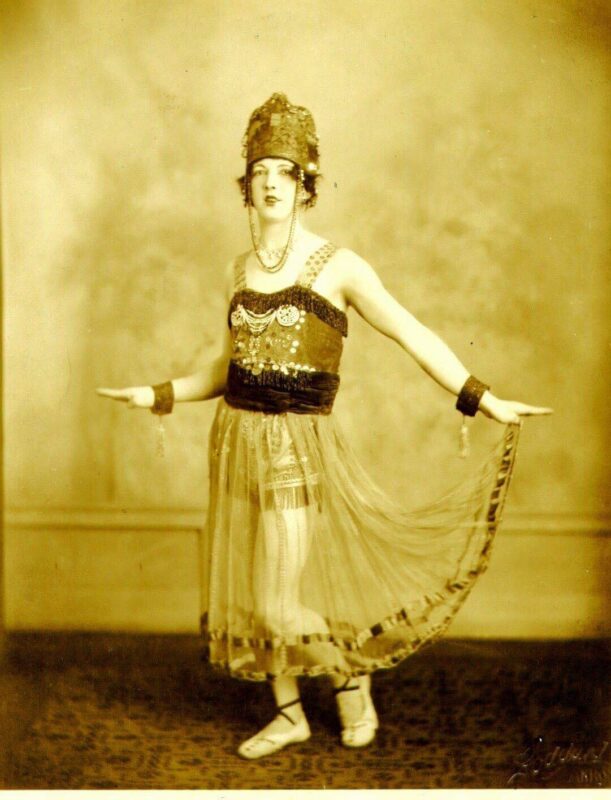

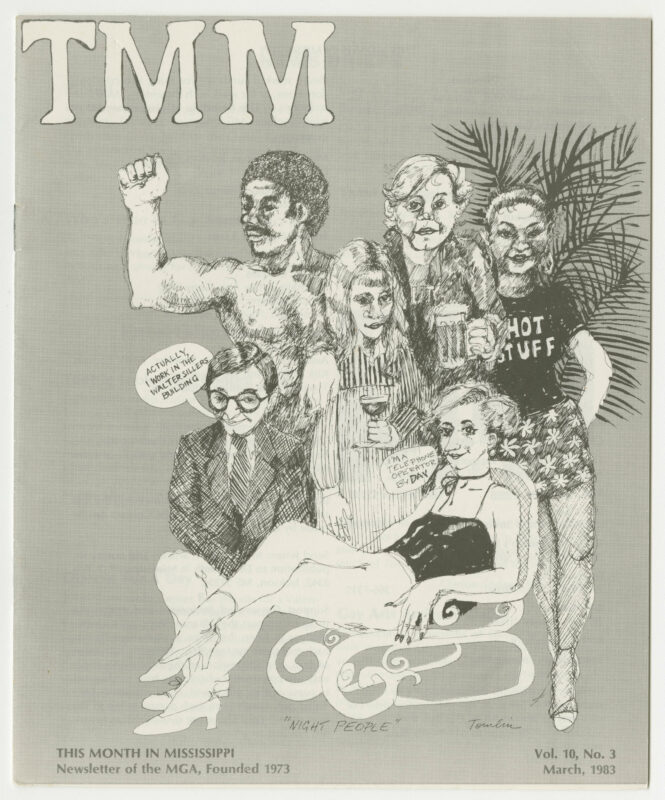

On top of that, their latest program teaches folks in the community how to properly collect and archive decades of photos, press clippings, and other materials chronicling struggles, triumphs, and celebrations over several generations. [Check out the photo from the 1920s below. Isn’t it amazing?]

Let Maigen tell you more about her’s and Josh’s boot-strap original story and the incredible progress they’ve made preserving the history of the Deep South’s LGBTQ community.

Postindustrial: What inspired you to create Invisible Histories?

Sullivan: In 2015, my co-founder, Josh Burford, and I reconnected at a Southern LGBTQ issues conference after several years living in different cities. I was co-hosting the event and Josh was there presenting his work in Charlotte to preserve the local community’s history.

We started talking about this work and how, quite frankly, we were unsatisfied with both our academic and student affairs roles in higher ed. This meeting led to a series of virtual events, mostly over Skype — if that tells you how long ago it was — where we planned out what an organization might look like.

Three years later, Josh quit his full-time job and started collecting our archival materials in February 2018. At the time, all we had was hope, nonprofit status, and about $1,500. In September of that year, I was able to come on full time as well. Some of the main driving motives for starting this organization were:

- We were tired of the South being overlooked or misrepresented in queer history and

- We felt the diversity and inclusion work we were doing on college campuses were too empty, performative, and not situated in any local culture or history. We wanted to change that. So now our efforts focus not just on telling Deep South queer and trans history, but on challenging traditional history, archiving, and educational institutions to think and practice differently, particularly in their efforts to save local narratives.

Postindustrial: What challenges have you faced chronicling LGBTQ stories in the Deep South?

Sullivan: The largest issue we have faced is funding. This might surprise readers, but trying to raise enough money to cover the amount of staffing and resources required to do this type of regional work as a humanities-based nonprofit in some of the poorest, least resourced states in the country is quite challenging.

While we have had phenomenal support from state humanities councils and our phenomenal funder, the Mellon Foundation, it still remains difficult to secure the needed amount of funding in a region so high in direct service need and with little free flowing capital.

People may think the persistent homophobia and transphobia, particularly at the state level, is our largest hindrance, but Southern queer folks are resilient and it has only empowered us to tell our stories clearer, louder, and more widespread than ever before. Last year, we did have an issue where I gave a talk at the Alabama Department of Archives & History that got some of our absolutely stellar state politicians’ panties in a wad — and they tried to shut down the talk, get their online ghouls to harass us, and punish the archives. However, the talk went on successfully and we have recently collected our 150th archival collection, so it clearly did not hurt the work we do.

Postindustrial: You have an exciting new program at Invisible Histories called the “Community Archivist Project.” What’s that all about?

Sullivan: The Invisible Histories Community Archivist program grew out of demand that we train local people who are not formally educated or experienced in community archiving or public history work on how to save their own community’s stories.

We are hosting our first cohort this year, and going forward each year, Invisible Histories will select 8-10 individuals/organizations to become an Invisible Histories Community Archivist. IHCA selectees will enter a yearlong cohort to conduct at least one local community history project that will be preserved by Invisible Histories.

They receive virtual training on what it means to do community archiving work, how to save materials, and memory working tools to use in the field. Participants also receive a free Queer History Field Kit filled with supplies they can use to document their community’s stories.

Queer History Field Kits contain everything someone needs to begin their journey as a community archivist and public historian. Invisible Histories supplies these backpacks free of charge to all selected for the cohort. IHCAs are to use the supplies for their year-long project, but are encouraged to continue to use them long after and keep documenting their community.