ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week.

Two national civil rights groups accused Illinois’ third-largest school district on Tuesday of relying on police to handle school discipline, unlawfully targeting Black students with tickets, arrests and other discipline.

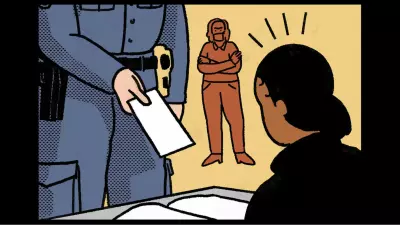

In a 25-page complaint against Rockford Public Schools, filed with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, the National Center for Youth Law and the MacArthur Justice Center said that Rockford police officers have been “addressing minor behaviors that should be handled as an educational matter by parents, teachers, and school leaders — and not as a law enforcement matter by police officers.”

The complaint adds: “Black students bear the brunt of this harm.”

The groups, which shared a copy of the complaint with ProPublica, asked the Education Department to find that the district violated federal law prohibiting discrimination and to order it to change its discipline practices and reliance on police. Using data obtained from the Rockford district and the Rockford Police Department, the groups argue that the district’s partnership with police funnels Black students — but not their white peers — into the justice system, even for the same infractions at school.

A spokesperson for Rockford schools declined to answer questions from ProPublica, saying the district had not been told by the Office for Civil Rights that a complaint had been filed and that it “will respond accordingly” if an investigation is opened.

The two national groups have won civil rights claims in school districts previously and also prompted change on criminal justice issues, such as solitary confinement in prisons. The groups began to investigate school-based ticketing in Rockford after a 2022 investigation by ProPublica and the Chicago Tribune into the practice in Illinois that included a database of thousands of student tickets issued across the state, including in Rockford.

“The Price Kids Pay” investigation found that even though Illinois law bans school officials from fining students directly, districts skirt the law by cooperating with police. It also found that Black students were twice as likely to be ticketed at school than their white peers.

The municipal tickets — for violating ordinances including those against vaping, truancy and disorderly conduct — can include fines of as much as $750 in Rockford and are difficult to fight. They’ve left some families with debt and other serious financial consequences. Unlike in juvenile court, students in local ticket hearings cannot get a public defender.

Rockford is the second large district in Illinois to face a civil rights investigation for racial disparities in ticketing since “The Price Kids Pay” was published. An investigation by the Illinois attorney general’s office into Township High School District 211, the state’s biggest high school district, was opened in May 2022 and is still ongoing, the office said Monday. The district has denied that students’ race plays a role in discipline there.

Using data obtained from the Rockford district and the Rockford Police Department, the groups argue that the district’s partnership with police funnels Black students — but not their white peers — into the justice system, even for the same infractions at school.

The Rockford district has about 28,000 students: 26% white, 31% Black and 32% Latino. The district oversees 41 schools for students in kindergarten through high school. According to the complaint, Black students were more than three times as likely as their white peers to be sent to a school police officer during the past three school years up until March.

As a result of disproportionate police involvement, the complaint alleges, Black students are then more likely to get ticketed. For example, at least nine Black students received police tickets for “trespassing,” or being on campus without permission this year. While 27 white students were accused of trespassing during the same period, none were referred to police or ticketed.

Representatives from the two legal groups said they attended about a dozen administrative ticket hearings, as recently as May, held at Rockford City Hall during the school day. They found that ticketed students were almost exclusively students of color.

“I have seen parents and families in the City Hall very confused and distraught that they were being ticketed for these things,” Zoe Li, an attorney with the MacArthur Justice Center, said in an interview with ProPublica. “The fact that I have not seen a single white kid at a ticket hearing in Rockford is a little surprising.”

Illinois lawmakers and advocates twice have introduced bills that would curb school-based ticketing in Illinois, including this spring, but both efforts fizzled. Even though the state schools superintendent and governor have said they support an end to the practice, some legislators and school leaders worry that banning student ticketing might unintentionally limit when police can get involved in more serious incidents.

But ordinance violations are by definition not criminal; students who bring weapons to school, for example, typically would be arrested, not ticketed. Rockford is a good example of the harm caused by ticketing and the need for a change in state law, said Angie Jimenez, an attorney focused on justice and equity at the National Center for Youth Law, which has pushed for reforms in Illinois law.

“The plan is to still move forward with the legislative advocacy to stop the practice of school ticketing,” Jimenez said. “We are hopeful that this complaint will help to support those efforts overall.”

The complaint also highlights racial disparities in discipline overall in Rockford. Black students are more likely to be suspended or expelled than their white peers, the groups found, even if the district’s code of conduct prescribed a lesser consequence such as detention.

The Rockford district has been the subject of discrimination complaints before. In 1993, a federal judge ruled that the district was illegally segregating students, including by steering Black and Latino students into lower-level classes. As a result of its disparate treatment of students, the district remained under a federal desegregation order until 2001.

Jennifer Smith Richards is a reporter for ProPublica pursuing stories about abuses by powerful government institutions and private businesses throughout the Midwest.

Jodi S. Cohen is a reporter for ProPublica, where she focuses on stories about schools and juvenile justice.