A North Carolina policy that denies state employees coverage for gender-affirming care has been on hold pending appeal. For one transgender worker still awaiting surgery, the anxiety is “like somebody has got their hands around my neck.”

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week.

In the spring of 2022, Hann Henson accepted a job as a communications specialist for a North Carolina school district. Not long after his insurance kicked in, he pored over the hundred-page booklet outlining the state health plan for district employees.

When he came to the list of services that aren’t covered, he paused at a tiny footnote: North Carolina’s plan did currently pay for gender-affirming care — but only because of a temporary federal court order.

Henson’s heart rate rose as he considered his options. Since he was a child, he’d been burdened by a sense of deep distress about the mismatch between the gender he was assigned at birth and the gender he knew himself to be.

Henson had grown accustomed to state leaders and insurance plans playing political tug of war with his rights. In 2016, early in his transition, a Republican governor signed into law the country’s first statewide ban on transgender people using the bathroom aligned with their gender — forcing Henson to worry about violence from strangers when entering public restrooms. A Democratic governor largely scrapped it a year later. Henson spent the next several years jumping through every hoop his insurance company required before it would cover one of his transition-related surgeries, with a representative at one point telling him the company didn’t cover “tranny health care.”

Now, yet again, he faced obstacles to health care access because of his gender identity. As Henson found out after he started his new job, North Carolina had been fighting a legal battle since 2019 against transgender people on the state’s health plan, some of whom had sued the state for coverage of transition-related care. In 2022, a judge ordered the state to cover the care while the fight dragged on. But any moment, another court ruling could whisk it away.

As Henson had become more confident as a transgender man, the world around him seemed to grow increasingly hostile, with conservative rhetoric against transgender people accelerating an avalanche of restrictive laws. In the last year, state lawmakers across the country have considered nearly 500 proposals targeting transgender rights, and more than 80 became law — both unprecedented numbers. This legislative session, North Carolina passed laws banning gender-affirming care for youth, limiting instruction in elementary schools about gender and sexuality, and preventing transgender girls from playing on girls’ sports teams. A Republican supermajority in the legislature overrode the Democratic governor’s vetoes on all three.

In May, Dale Folwell, North Carolina’s state treasurer, sat for an interview with a far-right activist to explain his decision to keep fighting the lawsuit filed by transgender people over the state health plan. North Carolina is one of more than a dozen states with a health plan that explicitly denies coverage for gender-affirming care, and this lawsuit — one of several arguing that states cannot block access to the coverage — is the first to make it to a federal appeals court. Folwell, who is running for governor, argued that the state health plan’s board of trustees should have the authority to determine the scope of employee benefits — echoing the argument North Carolina makes in court documents that covering gender-affirming care would be a financial burden.

“When you have a plan this large,” Folwell said in the interview, “you have to focus on doing the most good for the most number of people. That’s how you set benefits.” He did not respond to ProPublica’s questions or interview requests.

Lawyers and experts for the transgender plaintiffs have pointed to evidence showing that covering the care would likely cost the state very little — and have argued that withholding it is discriminatory.

For several weeks this spring, Henson repeatedly checked the federal court website for an update on the lawsuit, gripped by a feeling of panic, “like somebody has got their hands around my neck.” One more major surgery separated him from the relief of his body fully matching his gender, and he wasn’t sure when the court would make a decision.

A few days after Folwell’s interview, Henson learned that the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, based in Virginia, would hear arguments on the case in late September. It was far from the ideal time: His surgery was scheduled for late November, and he’d need a follow-up surgery about six months later.

The tight legal timeline has made the waiting period for the surgery almost unbearable for Henson: “You’re on the highway in the car and you’re driving and you’re like, ‘I’m gonna make it, I’m gonna make it.’ And then your gas starts running out.”

A 28-year-old self-described nerd with a youthful face and quiet voice, Henson distracts himself with his hobbies: playing video games with friends and attending anime conventions in costume. He regularly visits his parents in rural North Carolina and talks on the phone daily with his fiancee, who lives a few hours away. He has a calm demeanor, except for the nervous giggles that punctuate his speech, especially when he describes his darkest moments.

As the last academic school year came to a close, Henson stayed late to take photos at a school board meeting, sporting a blue suit jacket and hefty camera as he herded together groups of students and teachers who had won awards. He headed down the hall to his office to upload the photos. The live video of the board meeting played on the computer in the background.

Several minutes into the public comment period, a man approached the podium, introducing himself as a clergy member and a parent. His voice grew louder as he questioned whether board members were “perverts” and “child molesters.” He listed children’s books featuring transgender or gender-nonconforming characters and insisted they would be used to groom children, “push down their throat puberty blockers or move them towards mutilation.” As he began to read a passage from the Bible, his mic turned off. His time had run out. The audience applauded him.

Henson watched the screen, horrified. He felt like the man was speaking specifically about him. Few of his co-workers attending the board meeting knew he was transgender. He had cautiously told only his boss and closest colleagues, nervous about gossip or uncomfortable questions. Alone in the room, the office door ajar, he began to cry.

In recent months, Henson had often considered where he would be if the attacks on transgender people had been as aggressive when he first came out a decade ago as they are now. “I probably would be dead,” he said.

During Henson’s senior year of college, North Carolina passed House Bill 2, a prototype for the state bathroom bills that conservatives across the country stamped into law this year. HB 2 prohibited transgender people from using the public bathroom aligning with their gender and stripped the ability from cities and counties to pass local nondiscrimination policies. On the floor of the state House in late March of 2016, Republican lawmakers emphasized that the bill would help people travel more freely across the state, knowing each business would have the same policy.

Henson had moved cautiously through his college experience. Years earlier, as a freshman, he came out as transgender to his new group of friends. It was the first time he had been so widely open about his gender identity, and he hoped they would understand. Instead, they told him he was just looking for attention.

Already burdened by feelings of shame and low self-worth, Henson tried to kill himself. His resident assistant rushed him to the emergency room, where he told a doctor that he’d been stressed about chemistry class and a recent medication change, and had fought with a friend about “some kind of gender identity issues,” according to his medical notes.

Henson never spoke with those friends again, but their comments looped in his mind after he returned to school and continued to move forward in his gender transition.

In his senior year, after several months on testosterone, his beard had begun to grow in, and though it was patchy, he wore it like armor to shield himself from strangers’ scrutiny. It didn’t always work.

He remembers walking into one of the men’s bathrooms on campus the first week after the law passed. A man standing at the urinal turned and asked, “Are you allowed to come in here anymore?”

Henson frequently experienced panic attacks, fearful of potential assault and furious at public policies that restricted his rights. He recalls standing in the middle stall at school and sending an angry email from his phone to then-Gov. Pat McCrory: I’m a transgender man in a public men’s room. Come and get me.

In the months after the law passed, when he and his sister, Ashlee Park, ran errands at the suburban Walmart near her home, she stood outside the men’s bathroom protectively while he was inside. Park knew her brother was struggling. He had recently seen a therapist who waved away his gender dysphoria as a “pathological need to be different,” Park recalled. Since then, he had stopped mental health treatment and continued to spiral.

“He would say things that were just like: ‘I shouldn’t be alive. I’m an abomination,’” Park said. She would respond, “There’s nothing wrong with you. There’s something wrong with the world. You need to get out of your head.”

Henson couldn’t absorb her words. “It just felt like my state had said: ‘I don’t want you. You don’t deserve to be here,’” he said. “And when you’re told you don’t deserve to be here, you sort of feel like, ‘Where is there to go?’”

One day in the spring of 2016, Henson was visiting Park at her home. Park and her mother were about to leave the house, when Park suddenly felt uneasy. She went back inside to look for her brother and found him in her husband’s closet, looking at the collection of firearms in his gun case.

Henson immediately grew ashamed and pleaded with them not to tell anyone that he’d considered killing himself. “He was begging. I remember him standing on the landing in the studio and looking at me with these incredibly brown eyes,” his mother, Kim Crenshaw, recalled. “And telling me how hard it was for him to be in his body and to feel like such a freak.”

He asked his mother and sister not to take him to the emergency room. They agreed, under the condition that he find a good therapist, and they began calling him every week to ensure he was searching for one. Crenshaw thinks back on the effort it took to bring her son back up from his lowest point. “That scares me so badly for all the kids out there that are going through this now,” she said.

With his family’s encouragement and support, Henson began regular therapy after graduating from college and started to feel more comfortable in his identity. He decided to move forward in his medical transition, wanting chest reconstruction surgery so he could stop binding his chest flat every day. But the prospect of engaging with the health care system was daunting.

His medical records from past emergency room visits provide some insight into his experiences: Several times, doctors incorrectly referred to him as “female” (or, in especially erroneous language, as a “transgendered female”), at times using his previous name and alternating between pronouns.

In 2016, the Obama administration prohibited medical facilities and insurance companies from categorically refusing to cover all health services related to gender transition. But despite the new federal rule, his insurance company at the time, Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina, threw up barrier after barrier.

Henson recalled that on one occasion, while on the phone with the claims department, the person on the call threw out a transphobic slur: “We don’t do tranny health care.” He hung up the phone and burst into tears.

At the time, Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina required transgender patients seeking gender-affirming surgery to provide a supportive letter from a doctoral-level mental health professional — an incredibly high hurdle given the shortage of those providers across the country. After an exhaustive search, Henson found one in 2018 and later that year was able to get chest surgery. He remembers the surgery practice’s billing department filing an appeal with his insurance to get the procedure covered. Doctors there told him he was one of their first patients who received insurance approval for chest surgery related to a gender transition.

Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina broadened its policy in 2020 to allow any licensed mental health professional to provide letters for transgender patients seeking gender-affirming care. In response to questions from ProPublica, spokesperson Jami Sanchez said the company provides training on gender identity to its customer service team to “ensure members are treated with dignity and respect.”

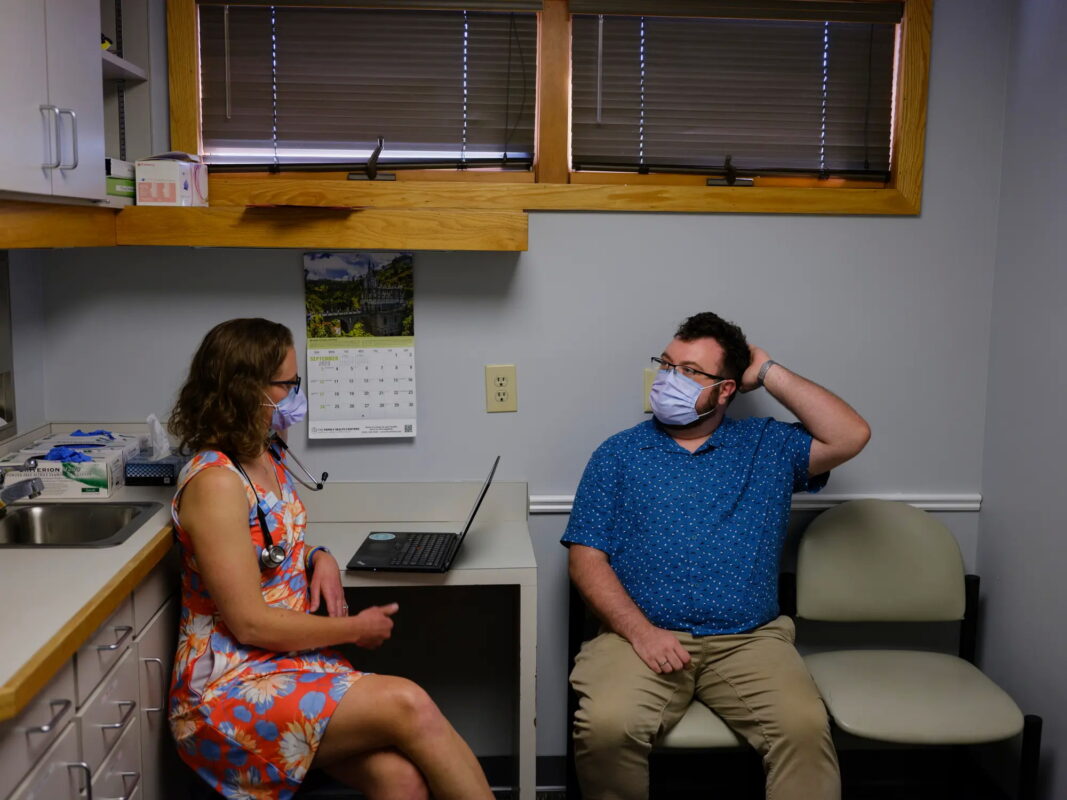

As the years passed, Henson found that more and more doctors understood how to treat transgender patients. After he took the job at the school district, he spoke with his general practitioner, Sydney Hendry, about getting a hysterectomy to treat the severe uterine spasms and cramps that can sometimes accompany testosterone therapy.

Hendry had to write a letter to the University of North Carolina Health surgical team verifying that Henson met the criteria for a gender dysphoria diagnosis and that a total hysterectomy would improve his quality of life. It was the first letter she had ever written for gender-affirming surgery. UNC Health provided a template that eased the process, avoiding the frustrating series of appeals and revisions that plagued Henson’s previous surgery.

Because of the federal court order, his state employee insurance agreed that it would cover the procedure. Henson had the surgery this March. But Hendry’s other transgender patients have told her that they’re scared about North Carolina limiting gender-affirming care for adults in the next year. “I tell them that they are my priority and that I will advocate for them,” she said.

“It feels like through my transition, there was this shift, where people became more educated about it and more knowledgeable,” Henson said. “And then in the past year or two, it’s starting to go back rapidly at a pace that is kind of scary.”

Henson feels that most people walking by him on the street see his full beard and stocky frame and don’t assume he is transgender. His fiancee, Aly Young, appreciates the sense of safety that comes with Henson “passing” but hates feeling like they’re hiding their true selves. “I don’t have thoughts in the back of my head like: ‘Should I be kissing him in public? Should I be holding his hand in public? Are people looking at us? Are we in danger?’” she said. “But at the same time, it makes me really sad. Because I don’t feel authentic. I don’t think Hann feels authentic.”

The two met when Henson began attending her small charter school in 11th grade, after years of home-schooling. One day, Young was hanging out in the hallway, when a math teacher called her over and asked her to comfort the new student crying in the bathroom. Young slowly coaxed Henson out and started to pursue a friendship. When Young moved away the following year, she kept in touch, writing letters that Henson now keeps in a box under his bed.

The pair talk often about moving away from North Carolina, even leaving the South altogether.

The South goes back generations in both their family lines, but this home feels increasingly hostile. Henson’s parents live in Sanford, where the Proud Boys showed up to a local brewery to protest a drag brunch. On the drive to Sanford, he passes by a supersized Confederate flag, which the Sons of Confederate Veterans erected in 2020 to protest the removal of Confederate memorials.

Looking forward, Henson counts down the days until his final set of surgical procedures, a genital reconstruction process commonly called bottom surgery. He had used up all his paid sick leave recovering from the hysterectomy, so he scheduled this next surgery for November, letting him use winter break to recover. Even if he is able to get the surgery before a ruling in North Carolina’s favor, the procedure requires a revision surgery about six months later, and Henson worries about being stuck with it incomplete.

On the morning of Sept. 21, all the active judges on the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals will preside over a second-floor courtroom in Richmond, Virginia, and listen to arguments from lawyers on both sides.

They will hear North Carolina’s case on the same day that they hear a similar one out of West Virginia that will determine whether that state’s Medicaid program must cover gender-affirming surgery. In both cases, federal judges in lower courts have already found the states’ policies discriminatory.

Recently, more than 20 conservative states filed an amicus brief in support of North Carolina, calling gender-affirming care “at best experimental and at worst deeply harmful” — a characterization that contradicts the consensus of major medical associations. More than 15 Democratic-led states wrote a brief in favor of the transgender plaintiffs, citing their own regulations that prevent insurance companies from “discriminating against medically necessary, transition-related care.”

In late August, Henson learned that the pastor who had railed against the school board back in June would soon be meeting privately with district leaders. He realized the man would be coming into the administration building where he works, meaning he could run into him face-to-face.

He thought about the benefits and drawbacks of not being immediately recognized as transgender: feeling safer but also forced underground, in a way, having to hear the vitriol against his community but powerless to stand up to it. He thought about how tired he was of feeling helpless and invisible.

That morning, he got dressed deliberately. Dress pants. A short-sleeved button-down shirt. And on the collar, a heart-shaped symbol of defiance — a pin in the colors of the transgender flag.

Aliyya Swaby is a reporter in ProPublica’s South unit covering children, families and social inequality.