Tara Collier doesn’t need new data to know how much the threat posed by COVID-19 has dropped in Michigan. The registered nurse at Sparrow Eaton Hospital in Charlotte lived through the days of jam-packed emergency rooms and the panic of patients — unable to breath and with few options — in the early days of the pandemic.

Now?

“I couldn’t tell you the last time I swabbed (a patient) for COVID and it came back positive,” she said. “It’s been a while.”

Probably two or three months, she said.

Collier is experiencing first hand the prolonged drop in Michigan of COVID-related hospitalizations and deaths — trends that bode well for a continuing ebb in the deadly disease that is blamed for the deaths of more than 38,700 Michiganders since March 2020.

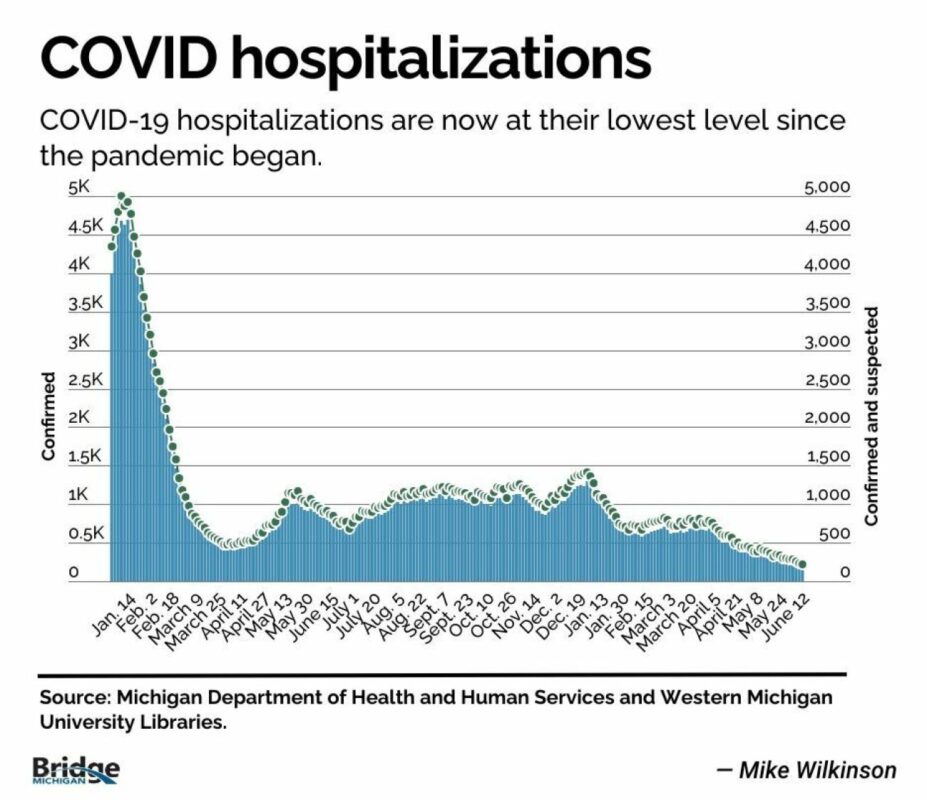

Hospitalizations are at record lows, with 219 patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 being treated statewide at hospitals as of Monday, down from 418 in May and 658 two months ago. At the peak of the Omicron surge in January 2022, there were over 5,000 COVID-19-positive patients in Michigan hospitals.

It’s part of a long and steady decline that began in March and mirrors steep drops in cases and deaths.

Consider:

- Just 18 COVID-positive patients across Michigan were in intensive-care units on Monday, according to state data. Since August 2020, when reliable data on ICU levels became available, that number had never dipped below 50 — a sign that the number of COVID-19 deaths will likely plummet as well.

- The 215 COVID-19 deaths in April was the second lowest — after the 150 in July 2021 — ever. And the state has recorded 113 deaths for May, though those will likely rise as more death records are analyzed and final.

- Another crucial metric — called the “r-naught” — has fallen to just below 1, according to the state’s latest data modeling report.The number indicates the “spreadability” of a disease. For every case of COVID, each infected Michigander, on average, will infect roughly one other person. In contrast, during the early days of the pandemic every infected person infected, on average, up to 2.4 other people, or even more, according to the World Health Organization and several studies.)

“It’s a really positive sign … that we have tools against COVID, and those tools mean that people are not getting significantly ill, they’re not ending up in the hospital, in the ICU on ventilators or dying as they did earlier in the pandemic,” said Dr. Natasha Bagdasarian, the state’s chief medical executive, told Bridge Monday.

The last time hospitalizations were this low — in June and July of 2021 — researchers were already anticipating the arrival of the Delta variant, which began hitting Michigan hard in August 2021, only waning just weeks before the Omicron variant shattered previous case counts.

There were hints of good news going back to this past winter. The winter’s surge peaked at 1,400 patients in early January, just a third of the previous year’s peaks, and hospitalizations have fallen steadily since March.

In addition to fewer patients, officials are detecting less COVID in wastewater surveillance, said Marisa Eisenberg, an associate professor of epidemiology and complex systems at University of Michigan. That’s important, because at-home testing results are now rarely reported, throwing off data that once tracked COVID spread.

“It’s not just that people aren’t reporting it,” said Eisenberg, who was part of the wastewater monitoring effort. “We really are seeing lower levels of COVID this time, which is great.”

Of course, real lives are still being lost — especially among seniors and people with chronic conditions — while many others have had their lives upended by long COVID.

And while patients are no longer waiting in packed waiting rooms and hallways for COVID care, the pandemic left scars across the healthcare system that won’t spring back easily, even if there are fewer patients testing positive.

Chief among them is a continued shortage of hospital staff. COVID drove thousands of workers — from doctors and nurses to support staff — out of the field, underscoring longstanding complaints among nurses and others of inadequate pay, brutal hours and not enough support from administrators.

“We’re down 8,500 nurses in the state of Michigan, and that has a very long tail on it,” said Sam Watson, senior vice president of field engagement at the Michigan Health & Hospital Association, an industry group.

“All the work that’s being done to try to get people into the pipeline (and) increase the number of nursing graduates … that takes time.”

Watson said that while hospitals are boosting recruitment and retention efforts, they also hope some of those “who left the field … will take a pause and come back.”

Experts acknowledge there are no guarantees the steep decline in cases, hospitalizations and deaths will continue. The virus likely will shift into seasonal patterns now, rebounding once again this fall, as the weather drives people indoors.

And like the flu, “there could be some viral respiratory seasons that are worse than others,” the state’s Bagdasarian said.

Another unknown is whether Michiganders will continue to seek out COVID vaccines as they are updated. According to the data modeling report, about 47 percent of Michiganders 65 years of age or older received the updated booster. But the overall rate, among all ages, was just 18 percent in Michigan.

The virus still “has the potential to develop these variants of concern and to spread in ways that we hadn’t really imagined in the earliest days of the pandemic,” Bagdasarian said. “We can’t really count anything out.”

Robin Erb leads health coverage for Michigan Health Watch. A long-time health writer, she documented the shock and grief of Michigan families in COVID’s wake, but also chronicled the triumph of research breakthroughs in the face of heartbreaking disease, the human spirit’s will to survive, and the policy shifts that will shape Michigan for years to come. Robin previously spent six years covering health at the Detroit Free Press, documenting the battle over — and the eventual passage of — the Affordable Care Act and Michigan’s Medicaid expansion.

Mike Wilkinson has been a reporter for Bridge Michigan since 2013 and focuses on data-assisted reporting, often finding stories by analyzing maps and data sets and has created Bridge’s dashboards on COVID-19, the state’s economy and Michigan’s elections. He held similar positions at The Detroit News and The Blade of Toledo.

Bridge Michigan is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that provides passionate and rooted Michigan readers with honest, fact-driven journalism on the state’s diverse people, politics, and economy. We serve as your watchdog on the biggest issues impacting your daily life, giving you insightful coverage you can’t get anywhere else. Receive Bridge in your inbox for free by subscribing here.