Rachel Bridgeman thought she could hear God.

Locked in the Allegheny County Jail, she slid from reality. The voice in her head, the one she called Lord Jesus, told her that if she smashed her face against the floor and walls of her cell she would save humanity.

Jail staff knew she had a history of psychosis and had spent time at two inpatient treatment facilities back in Georgia, her home. But as the conditions of the jail eroded Rachel’s sanity, a process intended to help her would keep her there longer.

The court needed to determine whether Rachel, then 22, would be “competent” to stand trial. The legal procedure is designed to protect someone, who because of a mental health issue, cannot participate in their own defense.

But for Rachel, referral to the competency system meant that, because of her mental illness, she could not leave the place making it worse.

A six-month investigation by Spotlight PA and the Pittsburgh Institute for Nonprofit Journalism found that Pennsylvania laws and policies meant to aid people who have severe mental health issues and have been accused of a crime often do just the opposite.

The investigation also found there is no single state agency tracking what happens to people once their competency is questioned.

Instead, a patchwork of state and local agencies facilitates the detention, treatment, and trial of someone found incompetent, with little oversight.

The result is a system that can strand people with serious mental health needs in jail, where their conditions may worsen; a system that prolongs detention for low-level crimes that experts say are often a symptom of mental illness; and a system so broken, some defense attorneys avoid it altogether.

The true number of people in Rachel’s situation — people spending extended time incarcerated in Pennsylvania because of mental health issues — is not known. Spotlight PA and PINJ discovered Rachel’s case only after advocates contacted reporters on her behalf and provided detailed legal and medical records.

The public records that do exist are scattered in courthouses across the state, on standalone dockets for individual cases. Among them, there is no standardized system for documenting competency assessments and hearings, and no easy way to identify people who may be stuck in jail and getting worse.

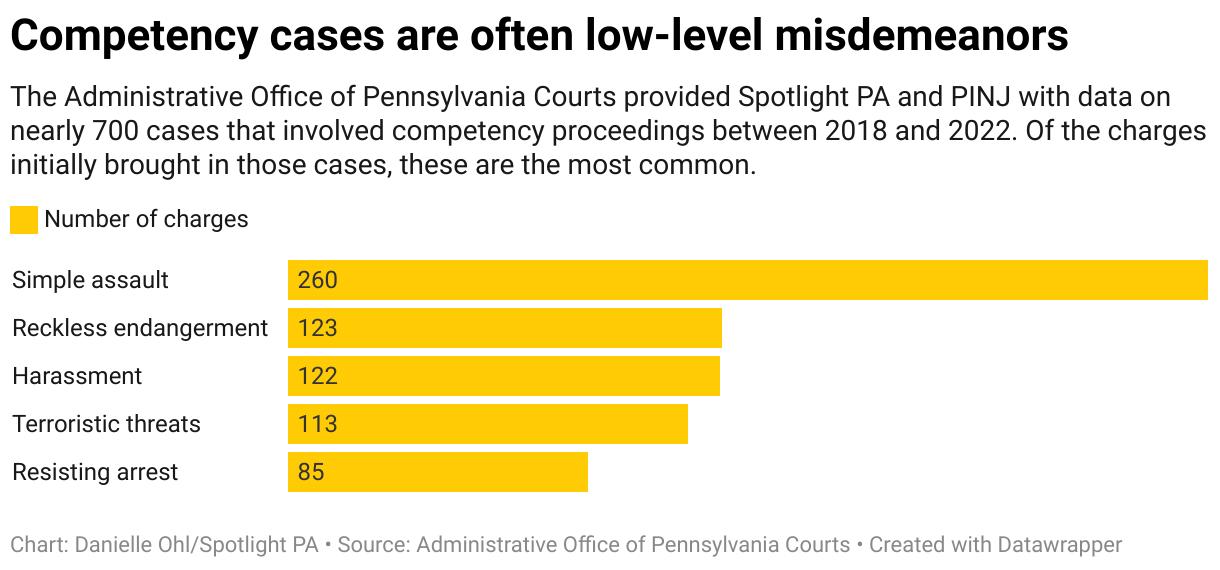

Spotlight PA and PINJ filed a request with the Administrative Office of Pennsylvania Courts, which maintains a management system for court records, for data from 2018 through August 2022 on cases involving questions of competency. Administrators identified more than two dozen terms that court clerks used to record competency proceedings.

A search using those terms yielded records of nearly 700 cases across 23 counties — only about one-third of the counties in Pennsylvania. The data do not include cases from some of the state’s most populous regions, including Allegheny County, where Rachel was arrested and charged. A court official in Allegheny County confirmed clerks there do not record competency proceedings on public dockets.

Public court records of Rachel’s case offer no indication she spent months in jail because of her deteriorating mental health. They offer no hint that she’d been deemed incompetent.

They do not show, as similar records do in other counties, that she sat waiting in a cell because she needed a rare open bed at one of only two state hospitals that provide “competency restoration,” treatment meant to improve a person’s mental health and help them understand the nuances of the legal system.

“The reality is that too many people with serious mental illness who do not have money in Pennsylvania are lost,” said Christopher Welsh, head of the Delaware County public defender’s office, where attorneys represent a large number of people in competency-related cases.

“Whether they are lost in a jail cell, they’re lost in the state institutions, or they’re lost because they’re hanging out on the side of the road and no one knows that they’re there, they are like the invisible people in our society.”

Minor charges add up in competency cases

Before the storm, things were never perfect for Rachel Bridgeman.

She’d lived “on the edge” from time to time, she said. She dropped out of high school. She lost her apartment.

But she’d also earned her GED. She got her associates degree and completed a job training program. She reconnected with her family after years of estrangement.

Things were getting better.

Before the storm, Rachel had just turned 22.

She landed a job she really wanted. And she met a man. To Rachel, a spiritual person, their meeting felt like divine intervention. Maybe she’d met the person she could spend her life with.

Instead, Rachel said, their relationship quickly turned abusive — the beginning of the storm.

The resulting trauma caused her to check into a local hospital for help, the first time in her life she’d sought treatment for psychological issues, she said.

But after her release, still feeling unstable, the two reconnected. The storm intensified.

They traveled from Atlanta to Pittsburgh, she said, where they were arrested in August and charged with promoting prostitution.

Rachel had never been arrested before and hadn’t contacted her family in Georgia in weeks.

The man she was arrested with found a private attorney and left jail three weeks later, according to public court records. The charges against him were later dismissed. Rachel, however, stayed behind bars.

Her mental health grew increasingly precarious, according to jail medical records. She was moved to an isolated cell in the jail’s mental health unit, where staff described her behavior as “odd, psychotic,” and “bizarre.”

She refused food, medicine, and clothing, the records show. She was intermittently put on suicide watch.

Medical staff referred Rachel to Allegheny County’s pretrial services department, an office housed within the court system, for a competency evaluation.

The Mental Health Procedures Act, a law enacted in 1976 and seldom updated since, governs the competency process in Pennsylvania.

Treatment to restore a defendant’s competency to stand trial is supposed to be ordered only if a judge is “reasonably certain” the person can recover. According to the statute, competency treatment cannot take longer than 60 days without a new court order. If a court finds the person cannot regain competence, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in 2022 gave judges the authority to dismiss charges.

Once a person is found incompetent, the act prohibits the case from lasting longer than a person’s maximum sentence or 10 years — whichever is shorter. The only exception is in murder cases.

But even when defendants face minor charges, the penalties associated with each count can add up, resulting in months or even years in jail before they see trial. Because of this, attorneys and advocates say that across the state, the system traps people in jail or in state-run psychiatric hospitals.

Rachel would stay in jail for another week waiting for a competency evaluation that would never happen. And then, abruptly, she was free to go. A judge had dismissed her prostitution charges.

County jails ill-equipped to handle mental health issues

The jail released Rachel around 5 p.m. on Sept. 22, and she boarded a bus wearing only a white T-shirt provided by the jail and the clothes she was arrested in: a black dress and slide-on sandals.

Rachel got off the bus on Pittsburgh’s south side. Hungry and underdressed for the 50-degree weather, she walked into a nearby Rite Aid.

She chugged a bottle of water, she said, and eagerly ate a bag of chips. She began to shop, placing items in a cart. A Rite Aid employee called the police to report a “shoplifting in progress,” according to a police report. Within hours of her release, Rachel was arrested again for retail theft and defiant trespass, minor offenses that come with a maximum sentence of 15 months in jail.

In response to a survey sent by the newsrooms, leaders of more than 20 jails across Pennsylvania told Spotlight PA and PINJ that jail can be a costly and harmful path for individuals who come to the facilities because of crimes that are likely a symptom of their mental illness.

But in Pennsylvania, jails are often the only place that can house a person whose symptoms have resulted in a call to police.

Since the 1980s, Pennsylvania has closed 10 state-run psychiatric hospitals, reducing the number of people annually receiving state-funded mental health care from more than 10,000 to roughly 1,383 on average in 2021. Today, there are six hospitals left. And just two — Torrance and Norristown — handle competency-related therapy, with less than 400 beds available for that purpose.

Supporters of the closures argued that with advances in medicine, people who could otherwise live independently were being unnecessarily committed. With proper community resources, they said, people could live with their mental health conditions outside state hospitals.

But in the years since, civil rights groups, defense attorneys, and corrections staff across the state have said the necessary community services never surfaced.

At the Snyder County Prison, “we appear to be a ‘dumping ground,’” Warden Scott Robinson wrote in response to the statewide survey. “It is very difficult to get detainees with serious mental health issues into an institution where they can receive proper care. Some can not even control bodily functions and it is a serious drain, mental and physical, on our staff.”

Some jail leaders who responded to the survey said that they are not equipped to provide adequate care for someone with mental health issues. Only six counties — including Allegheny — rated their ability to address the mental health needs of detainees a four out of five or higher in the survey.

Christopher Slobogin, director of Vanderbilt Law School’s Criminal Justice Program, said individuals with mental illness are often arrested on minor charges and then funneled through the criminal system because communities lack the resources to take care of them.

“They get picked up for crimes because police say, ‘What are we supposed to do with them? We’ll just arrest them for trespass or something,’ and then take them to jail,” Slobogin said. “And their life is probably made much worse. Usually the crimes they’re charged with are not a threat to society.”

Spotlight PA and PINJ obtained state court data on about 400 people who underwent evaluations for competency issues in the past five years. Though limited, the data confirm Slobogin’s assessment. Those defendants most often faced summary offenses, which are low-level crimes that typically result in little to no jail time, or misdemeanors, according to a Spotlight PA and PINJ analysis.

The most common charges — simple assault, reckless endangerment, terroristic threats, and harassment — can result from a person experiencing symptoms of their mental illness in public, said Witold Walczak, legal director of the ACLU of Pennsylvania.

“They don’t make sense. They’re loud. And people get scared,” he said.

People in these situations don’t need to go to state hospitals, Walczak said. Nor do they need jail, he added.

“They need help.”

Defense attorneys try to avoid struggling competency system

When Rachel was booked into the Allegheny County Jail just hours after her release, her mental health — well-documented from her prior five-week-long detention — prompted a new competency evaluation.

A judge denied Rachel’s bail, pending the assessment. The Allegheny Office of the Public Defender has said this is a common practice in the county. The office has challenged the practice of revoking bail for competency issues alone, calling it illegal and unconstitutional.

The Mental Health Procedures Act “states, in no uncertain terms, that an accused cannot be denied pre-trial release based solely on the fact that he or she has been deemed incompetent,” the office wrote in a May 2022 filing.

Joseph Asturi, a spokesperson for the Allegheny courts, said the administration had no comment on the public defender’s challenge.

Kate Lovelace, a private defense attorney working in Allegheny County, represents clients with intellectual and psychiatric disabilities whose cases often raise competency concerns.

When her clients face charges for minor infractions, Lovelace tries to avoid the court’s competency system altogether. Even the process of being evaluated can lead to bias, she said.

“When you’re trying to get out of an abusive institution like this, you don’t hang your hat on anything that could make it worse,” she said.

Attorneys with the Defender Association of Philadelphia, a public firm that provides no-cost legal counsel, said they also tend to avoid the competency system when clients with severe mental illness face misdemeanor or nonviolent charges.

“It’s not in our clients’ best interest,” said Gregg Blender, chief of the firm’s mental health unit.

Lack of beds leads to longer waits

On Oct. 12, a judge found Rachel Bridgeman incompetent to stand trial. But she doesn’t remember anyone explaining to her what that meant.

She didn’t know she was waiting for one of only 359 beds available for competency patients at Torrance or Norristown State Hospitals.

Waiting for treatment in a state hospital can take months. In one Beaver County case, someone languished at the jail for a year, according to officials.

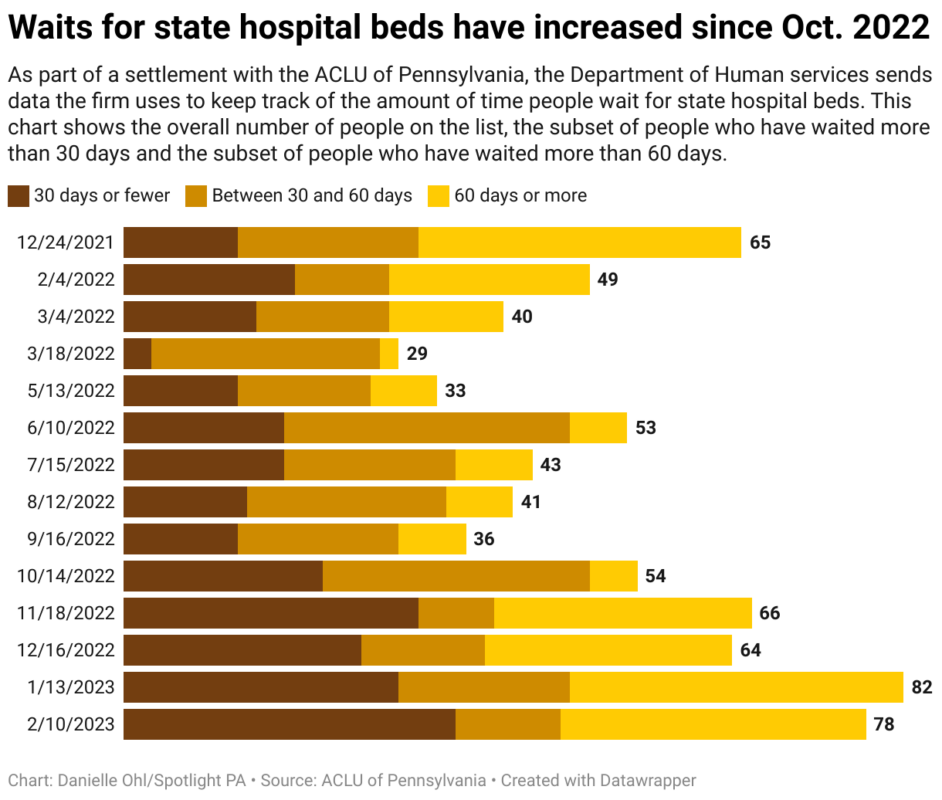

In 2015, the ACLU of Pennsylvania sued the commonwealth after two people died in jail while on the list for a state hospital bed. Less than a year later, the Department of Human Services (DHS) settled the case and agreed to reduce wait times.

Pennsylvania’s wait times improved nearly to the point of ending court supervision of the settlement in 2019, said Walczak, the ACLU attorney.

At the beginning of 2020, it took 15 days or less to get a spot in a state hospital, he said.

But wait times shot up again when the pandemic hit. More recently, there are people who have been waiting for a bed for more than six months.

Brandon Cwalina, a spokesperson for the department, said in a written response to interview questions that the pandemic affected wait times because a patient must test negative for COVID-19 before being admitted to a state hospital unit, and that the unit must not have an outbreak of the virus.

But even those numbers could be flawed, Walczak said.

“For the first time in several years, we’re not quite sure how reliable or comprehensive the data is that we’re getting.”

That’s because at the county level, “sometimes these people are sitting in jail for months before you get to the point where the court actually issues an order, which triggers the start time for getting somebody into treatment,” Walczak said.

Those months would not be reflected in the data the department sends the ACLU, according to Walczak.

DHS declined to make officials available for an interview with Spotlight PA and PINJ to discuss larger issues surrounding the competency process and state hospitals.

Cwalina said the department attempts to admit a patient to Torrance or Norristown State Hospitals within 15 days of receiving “all necessary information/documentation.”

In 2022, Rachel spent 49 days waiting for a bed.

In that time, her medical records indicate that she was tased, placed in a solitary padded room, and repeatedly injected with antipsychotic drugs.

The jail and Allegheny County denied requests from the Abolitionist Law Center and the newsrooms seeking reports documenting the force used against her.

A spokesperson for the Allegheny County Jail declined to comment on Rachel’s case, citing “personal medical information, and the safety and security of the facility.”

As Rachel’s condition worsened — her eyes blackened and bloodied, and her face swelled — at least one other woman on the acute mental health pod grew concerned enough to contact Jaclyn Kurin, a lawyer she knew at the Abolitionist Law Center. The center is a law firm that provides no-cost representation to people in jail. Someone needed to schedule a visit with Rachel Bridgeman, the incarcerated woman told Kurin. The situation was dire.

Rachel spoke with the attorney over a video call, bruises spreading like a Rorschach blot across her face. Kurin sent a letter asking the jail to take Rachel out of solitary confinement and improve her mental health care.

“Solitary confinement has caused Ms. Bridgeman substantial harm, including significant physical injuries,” the letter reads, “and ending her isolation is necessary to both protect her health and for the County to adhere to its legal obligations.”

After repeated visits with Kurin, Rachel began to feel more grounded. She started voluntarily taking her antipsychotic medicine. After Kurin sent the letter, the jail expanded her recreation privileges.

Rachel stopped banging her head on her cell. Finally, the voice was gone.

A sister clings to hope

It had been weeks since Sarah Bridgeman put up missing person posters in her home state of Georgia when Tanisha Long from the Abolitionist Law Center reached her family with news: They found her sister.

Sarah called the stranger from the law firm 700 miles away, who explained Rachel had been arrested and her court date was soon. Could she come up to Pittsburgh and make a case to the judge?

She didn’t know then how her sister wound up in Pennsylvania, let alone the Allegheny County Jail, but she bought a bus ticket without hesitation. As she traveled the 21 hours from Georgia to Pennsylvania, Sarah clung to a sliver of hope.

“If I just get down there, and I go to the court date, I know they’ll free her,” she remembered thinking.

But as Sarah sat in the courtroom, her hope began to fade.

There is no audio recording or transcript of the hearing that day, according to court officials.

To understand how it unfolded, Spotlight PA and PINJ spoke with Sarah and Long, who also attended.

During the proceeding, Sarah heard an Allegheny County assistant district attorney say the office wanted to continue the case against her sister for allegedly stealing and walking back into the store after the officer told her not to.

She should stay in jail for another month, the prosecutor said, and continue to wait for a bed at Torrance State Hospital.

Sarah made eye contact with the judge and began to cry. Long spoke up from the gallery. Rachel’s family is right here, she told the judge, who asked Sarah and Long to approach the bench.

Sarah came to save her sister because she knew if Rachel was left in jail, she wouldn’t last.

The judge dismissed the charges.

Sarah started screaming and crying in the courtroom. She hugged the public defender, her makeup streaming down her face and onto the lawyer’s clothes.

Rachel was free to go home.

A lack of comprehensive solutions

Freeing Rachel Bridgeman from the Allegheny County Jail took a broad group of collaborators: a fellow incarcerated woman, dealing with her own mental illness, who recognized Rachel needed help; an attorney and a community organizer, who met with Rachel and found her family; her sister Sarah, who traveled across several states to advocate for her in the courtroom; and the judge, who was willing to dismiss her charges.

That type of cooperative, community-based intervention is uncommon in low-level cases, advocates said, but may be necessary to keep people who need treatment for their mental illness out of jail.

In Philadelphia, attorneys with the Defender Association said they have worked successfully with prosecutors, judges, and treatment facilities to communicate the nuances of a case and redirect clients to treatment, if applicable.

But Bradley Bridge, an attorney with the firm, admits their method isn’t feasible everywhere.

That tailored approach “only succeeds based on the goodwill of all participants,” Bridge said. This includes judges and prosecutors interested in helping defendants rather than putting them in prison, he said. “It takes an empathy that is oftentimes absent in other [forums].”

Across Pennsylvania, some local governments and police departments are working toward piecemeal attempts to fix the competency system and ensure people in crisis receive health care instead of jail time. But the state currently lacks a comprehensive solution, experts told Spotlight PA and PINJ.

Some jurisdictions outside Pennsylvania have found alternatives, said Slobogin, the Vanderbilt professor. In Florida’s Miami-Dade County, court officials automatically divert people who have serious mental illness and face misdemeanor charges to a civil system.

Pennsylvania needs resources outside of the criminal justice system to ensure jails aren’t the “de facto social worker,” wrote David Kratz, director of the Bucks County Department of Corrections, in response to the Spotlight PA and PINJ jail survey.

“If services in the community are not easily available to law enforcement, jail is the easier alternative,” he said.

DHS in December provided $8.25 million total to six counties for residential programs and other mental health resources. The department estimates the funding would help serve about 390 people annually and reduce counties’ reliance on criminal units in state hospitals.

And state court administration has created a new position that will focus on developing, implementing, and assessing court programs to improve the process for people with mental health needs, said spokesperson Stacey Witalec. “This will include collection and analysis of data on mental health issues in the courts and making pertinent recommendations,” she said.

Some Pennsylvania counties, including Allegheny, are exploring programs that would cut down on wait times for state hospitals and instead bring competency restoration therapy and additional mental health services to the community and the jails.

But in-custody treatment and restoration is still a criminal solution, Slobogin said.

“I’m not trying to say, ‘Well, there’s an obvious easy fix to this,’” he said. “But if you’re going to try to do something about it, using the criminal system is probably the worst way to go.”

This story is a collaboration between Spotlight PA and the Pittsburgh Institute for Nonprofit Journalism, published as part of a Pittsburgh Media Partnership project.