The economic downturn for newspapers in the 2000s shuttered several small, community outlets, creating voids in local coverage throughout the country.

But in some communities, students, journalists and residents are creating hubs for local news, including programs in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Kentucky.

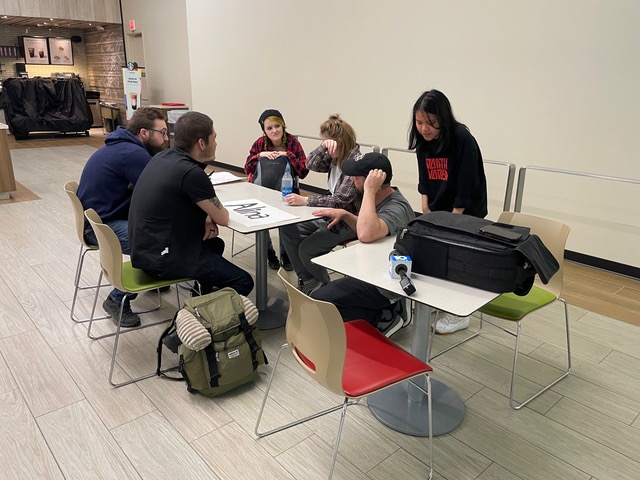

One program is the Reporting Project at Denison University in Granville, Ohio, about 30 miles west of Columbus. The project pairs student journalists with faculty to augment local news coverage.

Jack Shuler, a professor and author who runs the Reporting Project, said students were producing “really great work in class, stories about this community” that deserved a wider audience.

“For a while, we didn’t have a way to get those stories out to the world, and a platform to get it to people,” he said.

For the Reporting Project, they built a website, thereportingproject.org, to publish reported stories by the students and faculty, and to collaborate with area news outlets.

The first project was in February 2021 — a month-long series about Black lives in Licking County, in collaboration with the local chapter of the NAACP and the Newark Advocate. Each story was published in the newspaper and the website.

They now have five paid student interns and five faculty working on it.

“We think this is an important thing to do,” Shuler said. “Slowly, but surely, we get stories into the Newark Advocate and Columbus Dispatch.”

Both are larger, nearby outlets whose newsrooms have reduced staff in recent years, hampering their ability to provide regular coverage to smaller, nearby communities.

The most recent, big story The Reporting Project tackled was an interview with a student who was trying to get out of Ukraine amid the Russian bombardment and return to Columbus. They tracked her down, through her friends, and wrote a story that was published in The Columbus Dispatch.

“We can turn it around very quickly,” Shuler said.

This year, the students also are concentrating on reporting more about Intel’s plans to build a semiconductor chip manufacturing facility on 1,000 acres about 12 miles west from Denison. Intel plans to employ thousands — to build the facility and then manufacture the chips.

“It’s going to change this community,” Shuler said. “Some will feel better; some will feel like this is a loss to this community.”

Junior Jennifer Clancey, 21, a psychology major with a concentration in narrative journalism, says she loves working on the Reporting Project.

“You have people that are pushing you to write thoughtfully and really get involved in the local community,” Clancey said.

In Western Pennsylvania, Point Park University has stepped in with grant-funded programs to boost community journalism.One such project is in McKeesport, where the Daily News closed in 2015.

“You had a newspaper for 131 years and suddenly there’s no traditional news,” said Andrew Conte, Ph.D., director of Point Park’s Center for Media Innovation.

“I have been interested in what’s going on down there,” he said. “We have been doing some basic things with young people, asking them what are the stories you see in the community? You have rundown playgrounds, abandoned buildings, and no one’s telling these stories.”

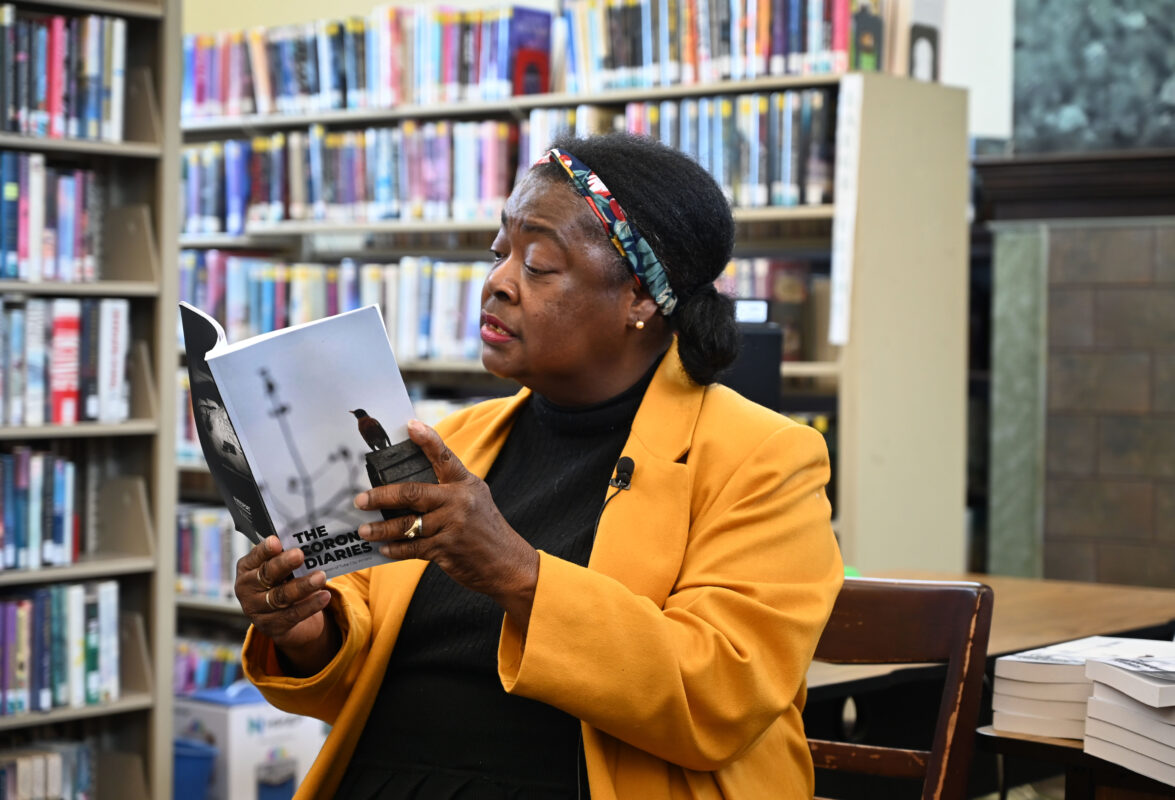

Point Park helped start a community journalism program in McKeesport, led by Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Martha Rial, who worked for more than 20 years at newspapers in Pittsburgh and St. Petersburg, Fla., as project director. The headquarters: The iconic Daily News building that’s more than a century old.

“The first thing I did was create a writers’ group,” Rial said. “I am very well aware of the fear many ordinary citizens have about writing — and they’re writing, that their writing is not good enough.”

She began a program called Tube City Writers in 2019.

“We had people as young as 16 show up, and people in their 60s. It was fantastic to have such a diverse group.”

They group also held a live reading, started a photography workshop, held an exhibition of their work, and during the COVID-19 pandemic maintained a blog, a collection published as “The Corona Diaries.”

“We are here to complement each other,” Rial said. “My group represents a wide range of interests and I want them to know that it’s hard work reporting on a community and a lot of responsibility comes with that. … I see it as building community by sharing your stories and the stories of others.”

There are other programs, too, that promote rural and community journalism.

The University of Kentucky has run the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues for 18 years. It’s a program with partners in more than 25 universities and colleges nationwide. It publishes The Rural Blog, described on its website as “a daily digest of events, trends, issues, ideas and journalism from and about rural America.”

The institute’s mission was to help rural journalism to define the public agenda in their communities, but, in the past decade, “we have focused more on the business side and the sustainability of rural newspapers because you can’t define the public agenda if you have no newspapers,” said Al Cross, the institute’s director.

He said local newspapers can sustain themselves if the communities they cover are sustainable.

“If you have a growing community, the news ecosystem ought to be OK,” Cross said.

Many news publications also depend on financial support from their audience, which means the standard of journalism needs to be high.

“People are not going to pay good money for bad journalism,” Cross said. “It requires rural journalism and community journalism to get better.”

One common thread in community journalism, he said, is timidity — publications fearful of angering their advertisers or public. But, sometimes, that’s inevitable.

“You have to help people understand it and get through it,” Cross said. “They have to help people understand the difference between news media and social media.”