One summer night last year, air began flowing into a steel canister across the street from the Little Bo Peep Child Development Center in Calvert City, Kentucky.

The pollution monitor hummed into the morning as parents dropped off their toddlers and later into the day as the kids played outside. Within a month, a lab analysis would reveal that the canister had captured a troubling concentration of ethylene dichloride, which has been linked to pancreatic and stomach cancers and leukemia.

No one, however, raced in to warn parents or alert nearby residents that the air they sucked in with every breath was laced with a poisonous chemical. No one took immediate steps to stop the stream or sue the offending polluter into compliance.

In fact, that Calvert City monitor had been running all year, along with two others around town. Each of them had registered more ethylene dichloride than any of the 123 other monitors nationwide designed to detect the chemical.

The results had been logged by Kentucky regulators and uploaded to a database managed by the Environmental Protection Agency.

If my child attended that day care, “I would be very concerned and working tremendously to get them into another school,” said Wilma Subra, an environmental health expert who advises the EPA on community concerns, after reviewing a summary of the air-monitoring results at ProPublica’s request.

It’s examples like Calvert City, experts say, that expose an infuriating conundrum with the U.S. systems for protecting citizens from dangerous pollution: Regulators install air monitors to flag hazardous emissions from local companies, then pull their punches in taking action against the offenders.

Meanwhile, the monitors serve as a false promise to residents that the findings will be used to keep them safe. Some people believe the mere existence of monitoring is “protecting them” from harm, said Barbara Morin, an air pollution expert at a nonprofit that advises the environmental regulators of eight Northeastern states. “Unfortunately, sometimes there’s just the monitoring and nothing happens to change the situation.”

ProPublica spent the last year crisscrossing the country to detail the failures of the EPA and state regulators to measure and address the community impacts of industrial toxic air pollution. The series of stories resulted in immediate response, including promises by the EPA to install monitors and track outputs — a move hailed as a victory for local communities. Residents of many of the toxic hot spots had spent years begging regulators to install them.

But an examination of the long history of air monitors in Calvert City shows that even when the monitors capture years’ worth of evidence that a polluter is putting a community in harm’s way, the path to clean, safe air is rocky and filled with well-funded obstacles, misdirection and inaction.

In this remote industrial city of 2,500, where manufacturing has long been king, regulators have had proof for at least three decades that residents are breathing dangerous amounts of air pollution. During that time, the EPA and the state have amassed an extraordinary amount of documentation establishing not just how hazardous the air is in Calvert City, but where the worst pollution is coming from.

They’ve watched in real time as the problem got worse and as the estimated cancer risks of area residents crossed the threshold level that the EPA considered acceptable — in places, reaching 17 times that limit.

Nicole Deziel, a Yale epidemiology professor and environmental health expert, said it could take decades to see the damage. Researchers often find themselves lagging behind, studying emerging cancer clusters and trying to reconstruct the cause, Deziel said. In Calvert City, where there’s already data that pollution levels exceed what’s considered safe, “we have the opportunity to actually intervene,” she said.

State and federal regulators have an arsenal of ways to do so and hold the culprits accountable, including levying millions in fines, requiring pollution controls and launching criminal investigations.

And yet, as the history of Calvert City shows, such action isn’t a given. In the face of a global petrochemical corporation, in a company town where residents are reluctant to criticize their employers, regulators have, again and again, stopped short of using all the tools at their disposal.

“Good Neighbor”

Founded on a railroad stop near the Tennessee River, Calvert City began attracting industrial development after the Kentucky Dam brought cheap electricity to the region in the 1940s. By 2020, more than a quarter of the private-sector jobs in surrounding Marshall County came from chemical plants and other manufacturing, with wages well above those in other fields. Every year, local families gather for a “Good Neighbor Night” hosted by a collection of plants whose employees hand out free swag, such as lawn chairs printed with the companies’ logos, as a turtle mascot named Wally Wise Guy teaches kids how to shelter in place in the event of an industrial accident.

Westlake Chemical moved into town in 1990, expanding over time into three plants — a maze of industrial boilers, tanks and wastewater ponds, with innumerable smokestacks and vents and pipes. The plants make polyvinyl chloride, better known as PVC, and petrochemicals used in construction, packaging and other goods.

The company got regulatory permits that authorized it to release thousands of pounds of carcinogens a year, but almost from the start, additional, unauthorized releases accidentally seeped or leaked into the air, according to EPA records. It wasn’t just ethylene dichloride, but vinyl chloride, which is highly flammable and has been associated with brain, liver and lung cancers. (The company did not respond to multiple requests for comment).

While a few plants run by other companies nearby also emitted these chemicals, Westlake’s authorized emissions would come to dwarf theirs. According to the most recent four years of available federal data, Westlake released at least 48,000 pounds of ethylene dichloride per year; the other companies combined released just 1 pound. Westlake’s annual vinyl chloride emissions during that time were at least 28 times that of the others.

Within eight years of Westlake’s opening, state and federal regulators had already been alerted to problems at the sprawling compound. In the decades that followed, news articles and regulatory documents would chart the company’s checkered record with the chemicals.

In 1998, for example, Westlake told the EPA that it hadn’t released any ethylene dichloride into the water when it had actually released more than 8,000 pounds, according to an EPA complaint. In 2001, it waited more than an hour before reporting a 2,727-pound leak; the same happened four years later, after a release of 7,700 pounds, the complaint said. The company was supposed to immediately inform a federal center for chemical accidents if it leaked 100 pounds of the potent carcinogen into the air.

Shortly after that leak in 2005, the local emergency response system made thousands of automated calls warning residents to shelter indoors, The Paducah Sun reported. The system had been adopted after 5,000 pounds of leaking vinyl chloride caused a fire and explosion at the plant in 2002.

Despite the calls in 2005, a Westlake manager told The Associated Press that air monitors hadn’t detected the carcinogen outside the plant’s boundaries.

In 2010, the EPA took the aggressive step of announcing a consent decree, a settlement that involves complex negotiations with the help of the Department of Justice. Under the terms of the decree, Westlake agreed to pay $800,000 and create a vast leak detection plan. Failure to meet those terms could lead to daily penalties of up to $5,000. The EPA predicted this would force Westlake to cut emissions of vinyl chloride by 2,300 pounds a year and of ethylene dichloride by 1,300 pounds per year.

Less than a year later, more than 11,000 pounds of vinyl chloride and 2,000 pounds of ethylene dichloride streamed out of a hole in a piece of Westlake piping, according to state and federal records. The leak destroyed the EPA’s goal in a single day; the agency later found Westlake hadn’t inspected the piping for mechanical integrity.

“Negligence Loophole”

With that leak in 2011, state regulators believed they had three separate air pollution violations, but Westlake wielded its legal might to fight back.

In the company’s lengthy response to regulators, a Westlake manager interrogated the definitions of basic terms like “equipment leak” or “standard” and argued that none of the violations were valid. In response, Kentucky regulators rescinded one of them, noting that the federal rule only applied to leaks during startups, shutdowns or malfunctions. Then they offered a startling rationale: The leak didn’t count as a “malfunction” because the problem partly stemmed from “poor operations and maintenance.”

“We are left with this loophole,” the regulators wrote.

Experts say such exit ramps from regulation are not uncommon. The system often presents a “laundry list of defenses” to polluters, said Seema Kakade, a former attorney in the EPA’s civil enforcement division who is now a law professor at the University of Maryland. Some provide leeway for unavoidable accidents and some are negotiated end-runs around the rules by corporate or other special interests, she said — with large, wealthy companies poised to take advantage.

Westlake benefited from what was “basically a negligence loophole” that “allows plants to avoid accountability even for releases caused by their own poor operations and maintenance,” Jim Pew, an attorney for the nonprofit group Earthjustice, said in an email. His organization has spent decades advocating for stronger EPA rules.

Over the next few years, the EPA unearthed four more leaks caused by faulty inspections or testing. However, none of these incidents broke the terms of the consent decree, as the agency concluded that these leaks concerned “alleged violations” of a different regulation from the one cited in the consent decree, said Tim Carroll, deputy press secretary for the EPA. (Carroll said Westlake has continuously demonstrated compliance with the 2010 settlement.) Despite the continued problems, and additional leaks cited by state regulators, Westlake was able to expand one of its plants — a move with so little pushback from the state that then-Gov. Steve Beshear, a Democrat, attended the ceremony. (Beshear didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

In 2017, two state environmental investigators were on the highway when they spotted a plume of black smoke, which they traced to a flare at a Westlake plant. Flares reduce pollution by burning off toxic gases, and they’re much less effective when there’s visible smoke. When the inspectors parked outside the facility fence to take photos, a Westlake security officer came out “and, after we had introduced ourselves, asked us to leave this location,” an inspector wrote in a report, which they did. Hours later, the plume of smoke was still visible from 10 miles away.

Though this violation and others at the same plant could have entailed millions in penalties, the agency offered Westlake a $350,000 settlement, according to an email from Beth Clemons, a Kentucky environmental enforcement specialist, to Westlake. In the email, obtained through open records requests, Clemons called it “a good deal.”

Westlake flatly disagreed. “$350,000 may be a good deal if there were violations, which we clearly believe there are not,” Kevin Sheridan, a Westlake health, safety and environment manager, wrote in an email.

Clemons responded that state regulators believed “the violations are valid and we are pretty much in total disagreement with what you are saying.”

The parties eventually agreed on a $175,000 penalty and a list of required repairs — a sanction that experts say amounts to a financial hiccup for the corporation that owns Westlake. Last year, Westlake’s parent company, Westlake Corporation, reported $2 billion in net income from dozens of facilities across North America, Europe and Asia.

Such penalties are “like a nuisance to the facility. It doesn’t serve as a significant deterrent,” said Scott Throwe, a former senior staffer in the EPA’s Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance. Wealthy corporations see it as “the cost of doing business.”

In response to questions about the effectiveness of its enforcement actions, John Mura, director of communication for the Kentucky regulator, said in a statement that his agency “remains committed to safeguarding the health of all Kentuckians and believes that it has acted appropriately under its regulatory authority.”

Even the better-resourced EPA rarely seeks maximum fines, said George Czerniak, a former enforcement officer in EPA’s Midwest regional office. Doing so involves going to court, and there is no guarantee the judge will rule favorably. The risk, he said, has made the agency skittish about pursuing aggressive sanctions in court. In the 35 years he spent on air pollution enforcement covering six states, Czerniak recalled fewer than 20 cases that ended up before a judge or jury.

If the EPA is going to take a case to court, then it needs to be “assured this is an important case,” Czerniak said — and one that “we can win.”

Limited budgets and EPA leaders’ changing priorities drove a decline in EPA enforcement actions from 2007 to 2018, according to a recent EPA Inspector General report. In 2009, the office that manages Kentucky conducted 2,700 inspections and other related activities to ensure polluters were following the law; that number plummeted more than 50% over the next decade. After Donald Trump became president, his administration deferred more enforcement cases to the states; Throwe said state agencies are more hamstrung by political pressure and less able to act decisively. “That’s why EPA is supposed to be the neutral entity that goes in,” he said.

The EPA wrapped up another investigation of Westlake in 2019, issuing a consent agreement and final order for a series of leaks that occurred more recently. The order, which is less serious than a consent decree, came with a $49,000 penalty. The company also had to buy $183,500 worth of equipment for local emergency responders. Four additional EPA inquiries of Westlake violations over the past decade have resulted in less than $150,000 in penalties.

Throwe said it would have been more effective to require Westlake to install no-leak valves and other devices to reduce leaks.

“This shows how hard it is to actually effect change,” he said.

“You Can’t Use That”

Manufacturers in Calvert City benefited from yet another flaw in oversight: Even when regulators stocked the town with air monitors that logged damning evidence, bureaucratic bungles and missed opportunities rendered them virtually useless.

Alarm bells about dangerously dirty air began going off as far back as 2005. Some of the more than 10,000 air samples collected statewide by Kentucky regulators over the prior 15 years showed “levels of concern” in Calvert City, and officials announced a work group to investigate “elevated levels of hazardous air pollutants,” the Courier-Journal in Louisville, Kentucky, reported.

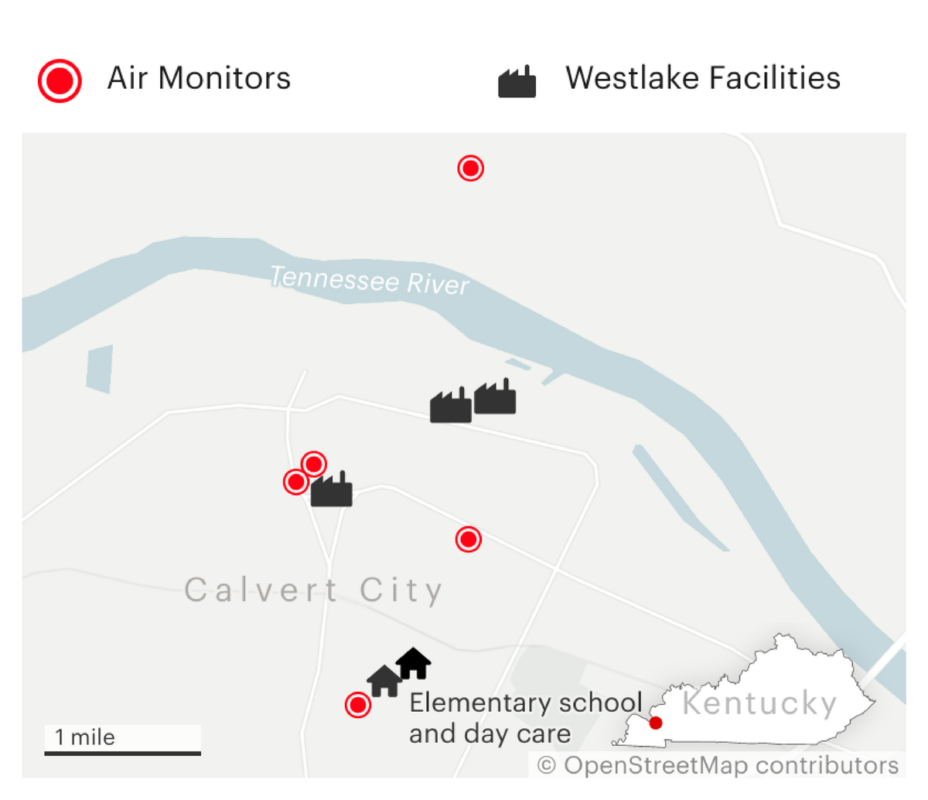

Between 2005 and 2007, state regulators installed five monitors in town, including the one at Calvert City Elementary School, across the street from the Little Bo Peep day care center.

Once every six days, the monitors took a 24-hour sample that was analyzed for ethylene dichloride, vinyl chloride and other hazardous pollutants. “What they’ve done here is way more air monitoring than what’s required by any EPA program,” said Morin, the Northeastern air pollution expert. “So the state clearly recognized there was some issue they wanted to deal with.”

By 2015, a quarter of the samples from the monitor closest to Westlake’s vinyls plant had levels of ethylene dichloride that violated EPA’s long-term cancer risk guidelines.

But an EPA audit that year found a critical flaw in the data; the state had never created a quality-assurance plan for the monitors, detailing the procedures to ensure that the collected data was reliable and accurate. Neglecting to do so, Throwe said, “gives ammunition to the industry to say, ‘You can’t use that.’”

Kentucky officials say they didn’t break any rules in their failure to implement a quality-assurance plan. But a spokesperson for the EPA regional office in charge of Kentucky said the federal government required such a plan.

The agency ordered the state to develop one in 2015, but two years later Kentucky still didn’t have one. By then, every one of the five monitors had captured elevated cancer risks, with ethylene dichloride and vinyl chloride the chief culprits. The EPA considers a 1 in 10,000 risk as acceptable, meaning that if 10,000 people in an area are exposed to a certain level of hazardous air pollution over a lifetime, at least one person would develop cancer as a result. (These EPA guidelines are used to calculate community cancer risk, and it’s nearly impossible to tie an individual cancer case to emissions from a specific facility.) In Calvert City, at least one sample showed cumulative risk as high as 60 times the limit, according to a 2017 risk screening analysis conducted by the EPA.

“Overall, the weight of evidence indicates that high levels of several VOC air toxics are present in the air in the Calvert City area,” concluded a report from Kentucky regulators and the EPA, while acknowledging that the lack of a quality-assurance plan “may affect the potential legal defensibility of the prior data collected.”

Mura said the state didn’t develop a plan because “no specific data monitoring objective was identified by EPA or Kentucky for the data collected.” Mura said his agency doesn’t know how many residents were exposed to those concentrations or for how long.

The failure to come up with a plan — rendering the results vulnerable to challenge — was baffling to experts and advocates. Monitoring for hazardous air pollutants is a costly, painstaking endeavor; no regulator would operate multiple monitors for years without a good reason, several experts told ProPublica. “You would think you’d want to get data that you can use,” Czerniak said.

And despite its worrisome conclusions, neither the EPA nor state regulators told residents about the cancer analysis. Billy Pitts, public health director of the Marshall County Health Department, said no one has contacted his office.

“We’ll Cross Those Bridges When We Get There”

It wasn’t until 2020 — five years after it was ordered to do so and 15 years after concerns about toxic air pollution were first raised — that Kentucky finally put in place a quality-assurance plan that would make the monitors’ data usable in serious enforcement efforts. It was the seventh straight year that one of Westlake’s plants emitted more ethylene dichloride than any other polluter in the country.

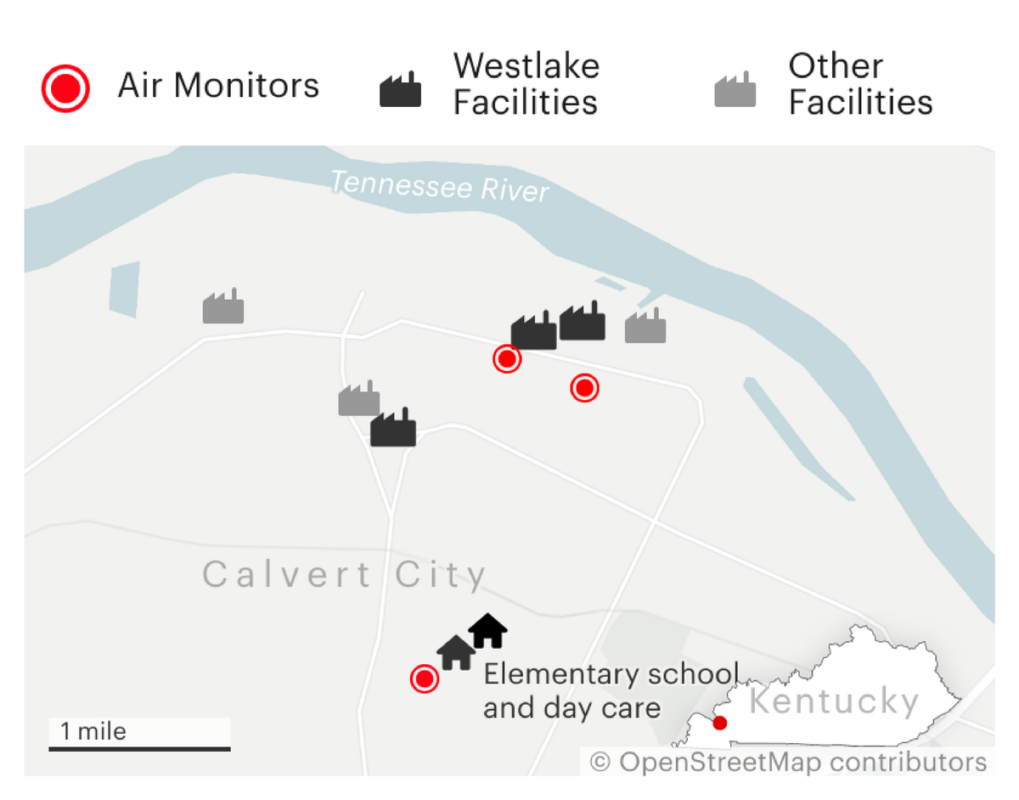

In 2020, the EPA installed new monitors in town after conducting air modeling to find the areas with the highest concentrations of the dangerous chemicals. The agency modeled vinyl chloride and ethylene dichloride emissions from the three Westlake facilities and three other nearby plants. Federal data shows that Westlake releases far more of these compounds than the other companies: Since 2010, only one of the non-Westlake plants has leaked vinyl chloride (a 15-pound leak in 2014), and none has leaked ethylene dichloride, according to state records. In contrast, regulators have cited Westlake at least a dozen times for leaking these and other hazardous compounds.

EPA and state regulators are analyzing data from the new monitors (and the one at the school) that was gathered from October 2020 to September 2021. A cancer risk analysis will be shared with the community once it’s complete.

If the results show a cause for concern, then “we’ll cross those bridges when we get there,” said Pitts, the health director, during an interview in his office. After ProPublica described the elevated levels from the past decade, Pitts said he wouldn’t “get too concerned until I see the facts that are presented.”

He later explained his department conducts a community health assessment once every three years, using data from local hospitals, schools and other sources. After ProPublica showed him air-monitoring reports from the EPA and state regulators, Pitts shared the materials with the team developing the health assessment, he said. The next assessment is scheduled for June, and the community would help decide the top public health concerns.

Interim updates from the current study, obtained through public records requests, show higher concentrations than the earlier data. While average ethylene dichloride levels at one monitor near the Westlake plants exceeded the EPA’s cancer risk guideline by 40% in 2017, the newer data showed the levels exceeded the limit by 600%. When ProPublica showed the data to Morin, the concentrations were so high in Calvert City that she initially thought there’d been a mistake.

Czerniak, the former EPA regional enforcement officer, said that if he were in charge, he would assign three of the federal agency’s technical experts and a couple of attorneys to do a deep dive on the Westlake plants and neighboring polluters. Czerniak has conducted similar investigations during his time at EPA, he said. If the agency found that specific air-permit violations at any Calvert City facility are pushing air pollution past acceptable cancer risk, he said, it should require the facilities to fix the root cause. If the excessive risk is caused by the sheer quantity of local facilities, the case could be referred to EPA headquarters with the request that tighter emission limits be put on these types of facilities.

In an email, Carroll, the EPA spokesperson, said the agency “is continuing to take steps to address noncompliance” at Westlake’s plants. In response to questions about the company’s pattern of violations, Carroll cited the ongoing study in Calvert City and said the EPA “will address any noncompliance identified using the appropriate enforcement tools.”

The EPA is also investigating Westlake’s flares at its Calvert City and Lake Charles, Louisiana, facilities, according to the company’s 2021 annual report to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. The EPA has worked on the case since 2014 and “indicated that it is seeking a consent decree that would obligate us to take corrective actions,” the report said. The decree could lead to penalties “in excess of $1 million,” the report continued. “We do not believe that the resolution of these flare matters will have a material adverse effect on our financial condition, results of operations or cash flows.” (An EPA spokesperson said the agency “cannot comment on potential or ongoing investigations.”)

It might be time to raise the stakes by building a criminal case against Westlake, Czerniak said, as even the threat of a criminal investigation could change the facility’s behavior. “I realize that agencies have limited capacity to undertake criminal-type proceedings, but heck, when you have a community that is exposed” to cancer risks up to 60 times the EPA’s acceptable limit, he said, “make no mistake … there are people who are being impacted.”

The motivation to hold the polluter accountable may need to come from regulators, as most residents ProPublica encountered in Calvert City were unaware of Westlake’s environmental record or the pattern of alarming air-monitoring data. When a reporter and photographer visited community leaders in March, we found that no one had heard of ethylene dichloride, and most did not know there was an air monitor at the school. Some expressed concern after learning about elevated levels of carcinogens.

“We know the EPA monitors the area,” said Tammy Blackwell, director of the county library system. “I would hope that if anything was significant enough that we needed to be made aware of it, the EPA would let us know.”

Marshall County Schools Superintendent Steve Miracle was even blunter: “You can’t just record it. … You would think if they’re the EPA, they can actually go in and help those companies come up with a solution for correcting that.”

Others did not want to talk about the companies that support the tax base and employ their friends and family.

Mayor Gene Colburn didn’t respond to multiple inquiries for this story, including messages left in person. (The mayor and three of the six City Council members work for local chemical plants, but not for Westlake.) The principal of Calvert City Elementary School, Kendra Glenn, declined through a representative to listen to a single question when ProPublica reporters visited in March.

Connie Monroe, who owns the Little Bo Peep day care across the street, said that she’d want to learn more about the pollution if it’s harming the kids she cares for, but that her husband recently retired from a local chemical plant. “It’s made our living,” she said, “so I’m not going to say anything critical.”

Chemical plants “do a lot for the community,” retired nurse Sherry Todd said on a recent spring day while watching her grandson’s soccer practice. The plants pay taxes that go toward “making Calvert City nice.” She had no qualms about air pollution or the plants hurting the town. “I can’t believe they’d do something intentionally,” she said.

About the Story

Last year, ProPublica conducted an analysis of data from the EPA’s Risk Screening Environmental Indicators model to identify hot spots of cancer-causing industrial air pollution across the United States. We then compared the results of our analysis to data from the EPA’s Air Quality System (AQS), which is a database of state, local and federally collected ambient air-monitoring samples. Because the EPA does not require states to set up air monitors near most major sources of toxic air pollution, we were unable to make comparisons in many of the hot spots that we identified. We filtered and sorted the data to understand which air monitors in the AQS network were picking up high concentrations of cancer-causing chemicals. Calvert City stood out, particularly for its concentrations of ethylene dichloride, a potent human carcinogen. Our analysis of the RSEI model indicated that Westlake was the dominant driver of cancer risk in Calvert City, so we began investigating the enforcement history of the facility and the reason the monitoring program was established there in the first place. We obtained documents through public records requests and correspondence with the EPA and Kentucky Division for Air Quality.

Lisa Song reports on the environment, energy and climate change for ProPublica.

Lylla Younes was a reporter and developer on ProPublica’s New Apps team.