The far-right is having a moment.

But what’s the endgame?

I recently put that question to Darrell Sivik, one of the early members of the modern militia movement.

“I’d like to see them start running for public office — local office, state office and your federal office,” said Sivik, who lives in rural Crawford County, Pennsylvania. “Get rid of those incumbent seat polishers. Get rid of those people, because they’re the ones that are causing the problem.”

In some districts, that’s exactly what is happening.

When you think of groups, like militias, your mind may wander to the deadly riot at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6. If you want to understand why the self-styled Patriot Movement matters right now, though, you might be better served looking closer to home.

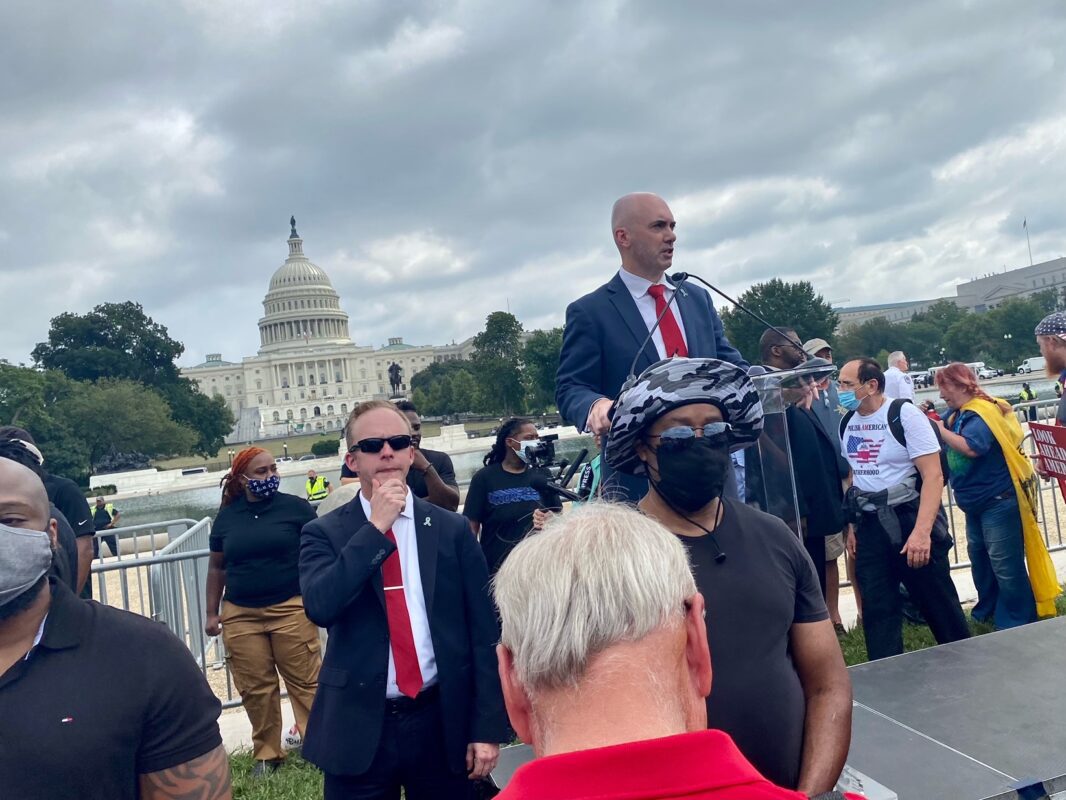

For the past three years, I’ve been reporting on the far-right, meeting with militia leaders, attending John Birch Society rallies and gun shows, and tracking the politicians who increasingly have been making common cause with the Patriot movement.

The next chapter of that work is Extremely American, a deeply reported podcast in partnership with Postindustrial looking at the nexus between far-right movements and mainstream politics.

I’ll take listeners on an immersive journey into the world of the American far-right, putting you on the ground at rallies, trainings, and and in the state capitols where they are increasingly gaining clout, and with the activists fighting back against them.

Subscribe to Extremely American on Apple, or listen wherever you get your favorite podcasts.

It’s a battle for the soul of the Republican Party and, maybe, American democracy itself, and it won’t end anytime soon.

On Jan. 6, there was a literal battle, as rioters brawled with police and chanted about hanging the vice president. But some far-right groups are quietly conducting political warfare below the radar.

Unlike at the Capitol, where a mob failed to overturn the presidential election, these groups are often winning seats on school, library boards, and city councils.

The Patriot movement encompasses militias, survivalist movements, groups such as Ammon Bundy’s anti-government People’s Rights movement in Idaho and the proto-fascist brawlers like the Proud Boys, who have a penchant for the former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet and firing paintballs at people they deem to be affiliated with antifa.

In some respects, they have proliferated during the COVID-19 pandemic on fears of government overreach.

But these are not reclusive 1990s militias hiding in the woods and eschewing the government they prepared to fight. That has given way to savvier leaders, many of whom say they want to change government from the inside.

Don’t get me wrong: Many people still train for guerilla warfare against what they see as a tyrannical government — they still stockpile guns and ammunition — but they’re also running for office, sometimes trading camo for suits.

Self-appointed defenders of the republic, they have their sights set on school boards, library boards, even grange halls, winnable elections that can have outsized effects on communities. But they have loftier goals, too — they’re looking to remake the country in their absolutist image. And to be clear, it is not to bolster democracy, at least not the way a lot of Americans think of it.

“We’re not a democracy; we’re a constitutional republic,” Patriot movement thought leader Alex Barron told me, a refrain I hear almost every time I attend a far-right rally. It’s kind of the leitmotif of the movement.

Barron, who grew up in Chicago but now lives in Idaho, had a follow-up:

“You can vote your way into an autocratic government, but often history has shown that you have to shoot your way out of it.”

Once anathema to any mainstream political party, militia members and other Patriot movement followers are in some areas embraced by the GOP now.

In Idaho, for example, the lieutenant governor uses Three Percenters as security and is close to the militia’s state leader.

In the crucial swing state of Michigan, the state’s Senate majority leader met with militia leaders, said they’re “getting a bad rap” and posed with one who is now imprisoned for allegedly being part of a plot to kidnap the state’s governor.

In Pennsylvania, state Sen. Doug Mastriano, a Republican and retired Army colonel, was amidst the mob outside the Capitol on Jan. 6 and joined some self-described militia members at a rally in Gettysburg.

Increasingly, the line between the far-right and mainstream politics has become blurred.

Militia members and other Patriot movement followers are running for office in Idaho, Washington, and other states, sometimes with the endorsement of the Republican Party. Some of them are winning. After a brief moment of widespread condemnation of the rioters who stormed the U.S. Capitol, many politicians have changed their tune.

Some have downplayed the seriousness of the insurrection, aimed at keeping Congress from certifying the election, while others are taking it further, calling those who were arrested “political prisoners” or even “hostages,” as Republican Congressman Madison Cawthorn of North Carolina put it.

A new crop of candidates, like J.R. Majewski, who was in Washington on Jan. 6, is running for office. And they don’t see their participation as a vulnerability. Majewski, who chartered a bus to bring people from Ohio to the Trump rally that preceded the insurrection, is proud of his role.

Daryl Johnson owns DT Analytics, which tracks far-right groups, and spent 25 years in the federal government monitoring domestic extremism. He said having some elected officials embrace once-fringe rhetoric and actions brings more people to extremism.

“The reason why we need to be concerned about it is because, as extremism becomes mainstream, it forces people to become more radical to be heard,” he said. “It gives this sense of having a permissive environment when you have politicians embracing these extreme viewpoints. It gives these people who embrace these extremist beliefs permission to operate and keep doing what they’re doing, which is recruit and radicalize people.”

Extremely American will be released early 2022, but stay tuned here, as I’ll be dropping reports along the way at Postindustrial.com and in Postindustrial magazine.

Sign up here to get the latest news about Extremely American, and to get the episodes first. Look for this original podcast produced and created by Heath Druzin, in December on Postindustrial.com, Apple, Spotify, and wherever you get your favorite podcasts.

Druzin traveled throughout the country to bring listeners a first-of-its-kind look and listen into the Patriot and militia movements, and why it should matter to you.