CLEVELAND — It’s mayoral season here and there are two candidates left: The millennial, nonprofit executive Justin Bibb, and the GenXer Kevin Kelley, the current City Council president.

As their candidacies have unfolded, so too have their talking points. Mostly, we’ve heard gaffless pedantics on each side about what the candidate thinks has or hasn’t worked in Cleveland (i.e., “We need to prepare our workforce,” “We need to fix the mismatch between open jobs and workless workers,” “We need to make our streets safe,” etc.).

Voters also have been bathed in the pale light that is the vague prognosticating about the future of Cleveland. Are we trending in the right direction? Regressing? Or stilled in a lukewarm bath of status quo?

While these platitudes and prognostications are not unwelcome, they have left the historians and policy wonks in all of us a little wanting. In fact, most politicians aren’t very good at offering a compelling vision of the places they represent. They also struggle with explaining how and why a city evolved the way it did — if only because they are pigeonholed into the local and thus unable to nest what’s local in the context of what’s global. This is unhelpful, because what’s global becomes local.

For example, the campaign trail, not surprisingly, has been littered with tactical talk: fix the permitting process, fix the deployment of squad cars, fix the recycling. No problem; it’s expected. But it’s only useful to a point. Because absent from the gazing through the navel is how these tactical issues manifest from our geopolitical reality. “[G]lobalization has been shown to increase the standard of living in developing countries,” explains a writer for the National Geographic, “but … globalization can have a negative effect on local or emerging economies and individual workers.” Put another way, geopolitical causes flap like a butterfly whose effect ends up in daily living on Cleveland’s streets.

Now, this is not a knock against politicians, local or otherwise. It’s only an acknowledgement of the constraints of politics, or the political milieu from which the politician is machined to operate. Politicians, after all, work in the time constraints of “short-termism,” in which the tactical for today continually usurps the strategic for tomorrow.

The philosopher Roman Krznaric notes this default setting toward short-termism flows from the electoral cycle, which he calls “an inherent design flaw of democratic systems that produces short political time horizons.” This, in turn, leads to myopic decision-making that keeps kicking proverbial cans down the proverbial roads.

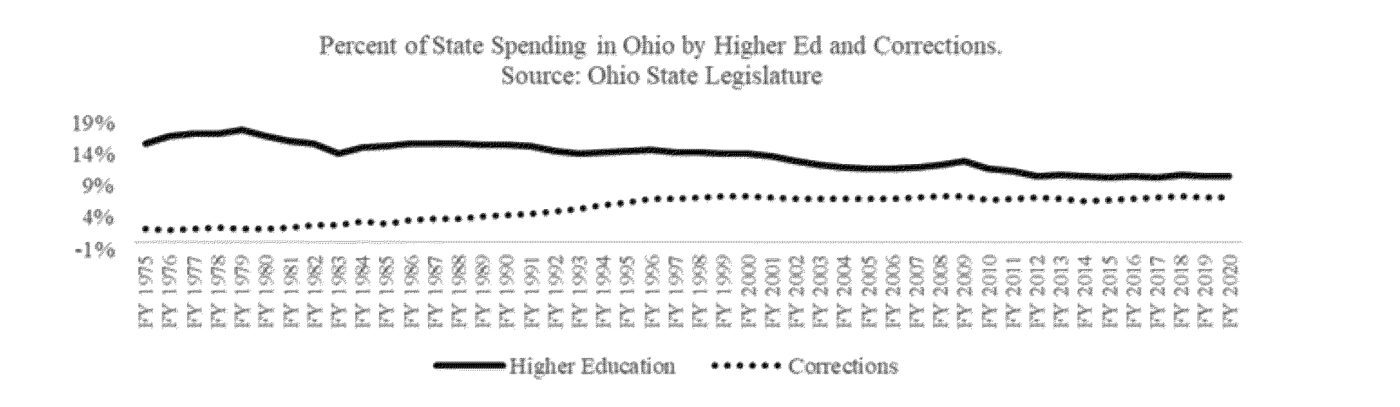

The figure below is illustrative. In 1979, Ohio allocated 17.7 percent of its budget toward investment in higher education. That’s down to 10.6 percent today. Meanwhile, spending on corrections increased from 2.2 percent to 7.1 percent over the same period. Such is the case of mortgaging the future to Band-Aid the present while neglecting the past. It’s policy quicksand that ends up sinking civil society.

Combatting short-termism entails creating, then institutionalizing, a long-term vision among policymakers. When I say “vision,” what does that mean exactly? It means trying to figure out what’s going on in this complex, crazy world and then thumbtacking Cleveland’s place in it, if only so the region has a compass to help guide it to move in accordance with the winds of change. Absent that, cities get left behind. “Globalization didn’t kill Detroit,” explains Jim Russell in the Pacific Standard, “globalization avoided Detroit.”

Below, the contours of a vision are briefly sketched out.

One of the most famous concepts in economics is that of “creative destruction,” coined by economist Joseph Schumpeter in 1942.

Creative destruction is a process wherein new technologies make the older way of doing things obsolete. There was the horse and buggy, for example, and then there were cars. Now there is Zoom. The shepherds of creative destruction, notes Schumpeter, are innovators and entrepreneurs who — while motivated by capitalistic gains — are also driven by the human instinct toward societal progress (Mark Zuckerberg notwithstanding.) After all, the lifeblood of innovation is to find a better way — or to make what was harder easier, or what was scarce more abundant.

The Industrial Revolution made the limits of manpower limitless by replicating it with steam and gears. The software revolution created a surplus of memory, unleashing information into our laptops and handheld devices. But progress doesn’t stop. Today’s value add is less about access to information than it is about making sense of it. It’s about knowledge. In fact, we have so much information that we are drowning in it, leaving us less informed, or worse: misinformed. Because while information is abundant, our ability to comb through it is scarce. The human attention span is limited. Explains Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, “Data is plentiful. Attention is scarce, and we’ll never get more of it.”

Enter artificial intelligence. The AI revolution is making the scarcity of human attention less so via the advance of cognitive computing. It’s the next “general purpose technology” to change the course of events, birthing a boom in our ability to find signals in the noise. As revolutions go, it is just getting started. “[W]hile we’ve seen the AI sun, we have yet to see it truly shine,” writes Craig S. Smith in the New York Times. “Researchers liken the current state of the technology to cellphones of the 1990s: useful, but crude and cumbersome.”

As the AI revolution inevitably unfolds, it will have a seismic impact that ripples across industries, firms, and products, not to mention the cities that make up the economic geography of those market entities. Elaborating, the Clevelands, Detroits, and Pittsburghs were kings when the steam engine and electricity changed the playing field. But as the global economy evolved from drill bits to data bits, the Rust Belt lost its global relevance. And it’s still fighting to claw its way back.

That’s because economic evolution is not played out evenly across space. As creative destruction happens, some cities win; most lose.

My research shows that only 13.4 percent of Cleveland’s economic output is from the information technology sector. In Pittsburgh, it is higher at 19.4 percent. Compare that to 34 percent in Boston, 43 percent in San Francisco, and 42 percent in San Jose, Calif. — home to Silicon Valley. And where tech clusters, so does wealth.

Among the largest 40 cities in the nation, San Jose is the most prosperous, with a real per capita income of $82,718, followed by San Francisco ($71,668), Boston ($64,783), and Seattle ($62,619). By comparison, Cleveland ($56,369) ranks 18th.

The solution? Become like Silicon Valley, naturally. That’s the most common, copycat response. In fact, this was the rationale behind Cleveland’s inane “Blockland” movement that took the city by storm circa 2018.

A briefer: Mercedes Benz salesman and current self-funded Ohio Republican Senate candidate Bernie Moreno was behind the initiative, which was meant to make Cleveland a global epicenter of blockchain technology.

Moreno was going to sell Cleveland as he would a 450 Coupe to blockchain technologists as the place to invest. Why Cleveland? No reason, really. No matter. He got the movers and shakers here all lathered up. And at not an insignificant cost of time and money, no less.

Alas, the effort quickly devolved into a thing called “City Block,” — which was a real estate project aiming to make Tower City, our Downtown’s defunct mall, an epicenter of technology start-ups.

That plan has devolved into a self-inquiring memory of “What the hell were we thinking,” — a memory that’s only alive as I write this. And dead as soon as I stop.

Nonetheless, such tech-incubating tactics are hardly unique to Cleveland. Cities everywhere want industries that are high-growth and hi-tech.

This has led to city-building strategies to be geared toward becoming “the next Silicon Valley.”

In fact, Philadelphia has branded part of its city as “Philicon Valley,” whereas New York has “Silicon Alley.” New Orleans has “Silicon Bayou” and Portland, Ore. has “Silicon Forest.” There’s “Silicon Swamp” in Gainesville, Fla.,“Silicon Slopes” in Utah, “Silicon Harbor” in Charleston, S.C. and a variant of “Silicon Prairie” in Dallas, Chicago, Omaha, Neb. and Jackson Hole, Wyo.

But there are fatal flaws in this approach. If every city wants to be the “next Silicon Valley,” then no city will be the “next Silicon Valley.” Economic development is about differentiation, not copycatting and sheepherding.

Still, there’s a flaw that runs even deeper than that, one unburied by the question: “Why be ‘the next Silicon Valley’ in the first place?”

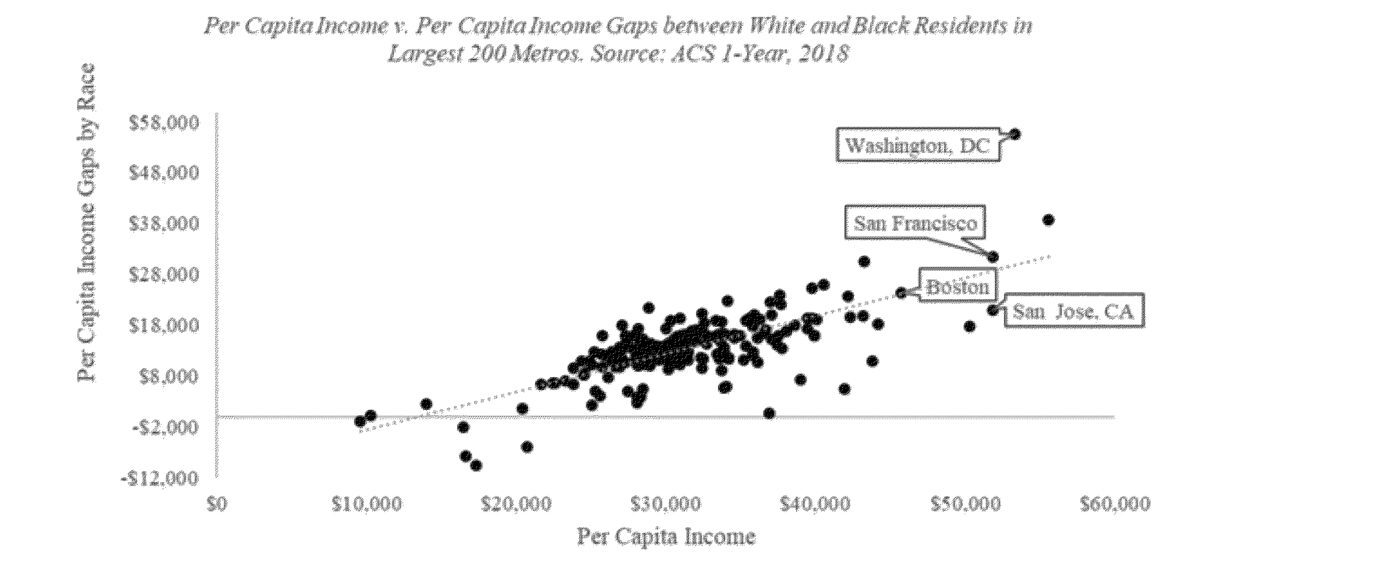

Note the figure below. It shows that the nation’s most prosperous regions are also the most disparate. That is, the higher a region’s per capita income, the larger the gap in incomes between White and Black residents. For those unfamiliar with scatterplots, that’s a pretty damn strong association between prosperity and inequity.

Now, if that’s success, I’d hate to see what failure looks like. And while Cleveland’s mayoral candidates surely will opine on the need for all things “hi-tech,” will they be able — or even try — to grapple with the inherent contradictions of modern capitalism?

I am not saying Cleveland shouldn’t innovate when it comes to economic development. That’s silly. It is only to acknowledge what even mainstream economists are acknowledging: Economic growth brings with it societal decline. Or, that progress does give rise to pain.

And while the above is not a complete vision for a post-industrial Cleveland, there’s a historically and theoretically sound context and direction that’s plotted out.

Here’s hoping the next Cleveland mayor has the clarity and patience to think long, hard, and correctly.

I don’t know how many more versions of the headline “From Believeland to Blockland” I can survive.