When a Florida company was looking to install a large-scale solar farm in Gettysburg, Clayton Wood didn’t think leasing his property to the company would be an issue.

“We are not putting up a laser tag place, or an amusement park. It’s just solar panels,” Wood said. “No traffic, no sewer lines, no extra taxes, maybe even a benefit to taxes.”

But after overwhelming public outcry, township supervisors deadlocked, and thereby rejecting the project. Developer NextEra appealed that decision to Common Pleas Court.

It’s a case that many others in Postindustrial communities may watch as more large-scale solar arrays spring up, the result of government incentives for “clean” energy and sometimes-lucrative returns.

NextEra’s 75-megawatt project would take up 1,000 acres in Mount Joy Township. It would be one of the largest, if not the largest, utility-scale solar installations in the Commonwealth.

“There is a place for solar, but this is not the place.” — Thomas Newhart

Ultimately, these developments generate power for companies, not individual homes.

Those who oppose the project didn’t want such a massive solar array in their backyards.

They point to the area’s agricultural setting and, more importantly, its proximity to the Civil War battlefields of Gettysburg.

“There is a place for solar, but this is not the place,” said Thomas Newhart, who raises black Angus cattle on a 65-acre farm. He and his wife bought the property 35 years ago.

In Pennsylvania alone, there are more than 300 proposed solar projects on the grid that guides electricity flow to 65 million people in 13 states and the District of Columbia. Only a fraction of these projects in grid operator Audubon, Pa.-based PJM Interconnection’s queue will come to fruition.

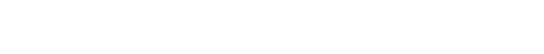

Leasing land for such projects is a winning proposition for many landowners: Rural communities throughout Postindustrial America are rich with swaths of land on which developers are paying owners generous per-acre fees to place solar panels.

“Our stance is we should be able to do what we want with our property and our land. … We have been hoping and wanting for this to come to a good conclusion sooner than later.” — Clayton Wood

Wood, 34, owns a dairy farm in Geneva, N.Y., but has a stake in his family’s former dairy farm, which encompasses about 200 acres in Mount Joy, about seven miles from Gettysburg.

He grew up on the farm. His grandfather and parents still live there, and Wood would like to leave the land to his two children, making them the fifth generation in his family to own it.

The solar project, he said, “added some sort of value to the community. We were getting some personal gain from it, of course, but who wouldn’t be looking for that?”

Wood called NextEra’s decision to appeal “great news.”

“Our stance is we should be able to do what we want with our property and our land,” Wood said, adding his family first met with NextEra in 2016, and “we have been hoping and wanting for this to come to a good conclusion sooner than later.”

Newhart and his allies vow to continue fighting against it.

Newhart said the solar farm would ruin his business, which includes the Iron Horse Inn, a bed-and-breakfast. Many guests have returned, he said, because of the undeveloped surroundings.

NextEra’s project would place an 8-foot barbed wire fence and 12-foot tall solar panels 50 feet from his property, Newhart said.

“This proposed project is mind-boggling. I mean, what are we doing?”

Wood said he is sympathetic to such concerns, but pointed out: “You don’t own your view. You own it if you own that land.”

He also is frustrated that his “neighbors’ concerns dictate to a degree what we can and can’t do on our property,” he said. “It’s not our community park.”

The issue is that the proposed project “interferes with everyone,” Newhart’s attorney, Nathan C. Wolf, said. “It’s an industrial-sized solar power plant that they put on ag(ricultural) land.”

His clients, he said, also are concerned about possible loss of habitat and potential environmental damage, including hazardous material in the solar panels.