In a community funded by tourism and affluence, much of Door County’s year-round and seasonal workforce is struggling to live comfortably.

Resorts, seasonal rentals, and second or third homes dominate the land, but without more affordable housing, the county could lose many of its employees.

According to a 2019 study by Housing Door County, three of the biggest forces driving the county’s demand for housing since 2010 are job growth; an expansion of tourism, particularly in northern Door County; and a heightened interest in second homes, especially for people in their 50s or 60s whose income is higher than the national median household income.

Many homes in the county — almost 10,000 as of 2019 — are in seasonal use but not rented. Based on interviews conducted as part of the report, some are empty year-round due to aging or busy owners and have the potential to support workforce housing.

Door County Land Use Services Department Director Mariah Goode said part of the housing problem is tied to construction costs, which have climbed higher due to the coronavirus pandemic and shortage of materials, slowing the construction of new housing.

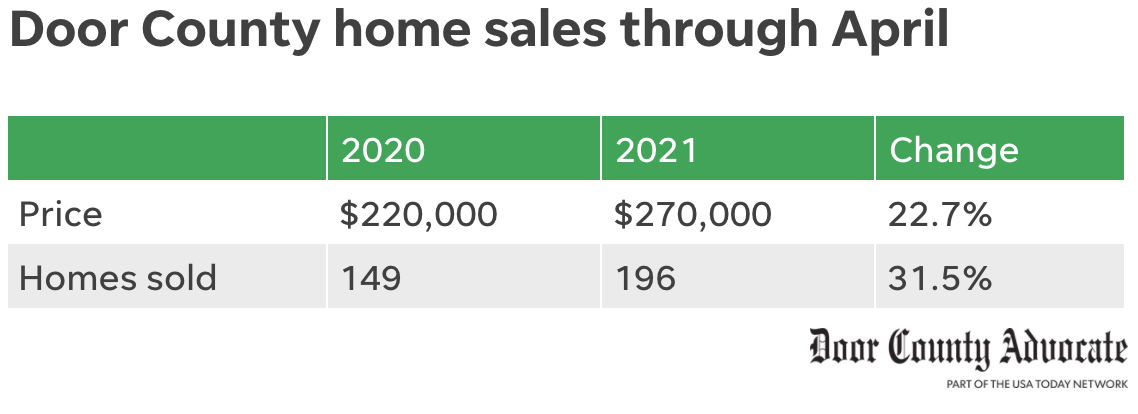

However, the pandemic did not stop a surge in the real estate market.

“People don’t even bother putting up ‘for sale’ signs here,” Goode said. “Something lists, and within a day, there’s multiple showings and multiple offers.”

Paige Funkhouser, now the Door County Maritime Museum’s community engagement manager, moved from Southern California to Sturgeon Bay in 2003, when housing was a little easier to find. A few years later, just before the recession hit in 2008, she moved further up the peninsula to the Gibraltar area, and spent a long time looking before she settled into a new house that she could afford that had propane heat.

“It was a beautiful house,” she said. “But here’s the problem: I set it on fire when the heat went out and I had to use the stove to keep warm.”

Luckily, she woke up before the fire spread past the carpet, but this wasn’t the end of her housing woes, as she later moved into a house where black mold grew on her walls, in her shoes and on her belongings.

Emily Johnson, a personal banker at North Shore Bank’s Sturgeon Bay location, also faced mold among other issues in a living space that was less than adequate, but affordable at the time.

“The day I moved in, the floor was flooded from the bathroom, and the floor squished when you walked on it,” she said. “In the same breath, I am very grateful for having a place when I needed it that was affordable for me.”

While they are living more stably now, Johnson and Funkhouser struggled in those times, working full time or holding multiple jobs, to stay afloat.

“I have always been raised that you do what you have to do to make ends meet and pay your bills,” Johnson said. “There were many years where I worked 60 to 80 hour work weeks just to be able to keep up, but that’s what I did.”

Funkhouser said she still notices that many residents earning modest incomes are paying so much for housing that they don’t have savings, and are barely paying the bills.

“Door County is one of those places people choose to live,” she said. “They like it here, but I’ve learned that after two or three years, they either make it or break it.”

Seasonal workforce housing is a unique need in Door County

The tourism industry raised the need for seasonal employees, which in turn raised the need for seasonal housing, one of the three main types of housing in short supply in the county, according to the 2019 county report.

The other two types are year-round workforce housing for employees earning 60% to 120% of the county’s median income, and year-round housing for independently living seniors ages 65 and older.

In 2019, the county had a workforce housing shortage of 470 apartment units, described in the report as a “basic mismatch” between job creation and new housing. The gap means that hired employees in Door County often have to live in another county for lack of suitable, affordable housing.

An employee who works in the county but has to live in Green Bay faces a long daily commute, which is seen as “prohibitive” to attracting employees, according to stakeholder interviews in the report.

Funkhouser has struggled to recruit both seasonal and year-round employees.

“I can’t recruit, because there’s no place for anyone to live,” she said. “We get a ton of inquiries, but guess what, the first question out of their mouth after ‘how much does it pay’ is ‘where can I live?’”

The housing needs of seasonal employees, especially workers on J-1 visas, for whom employers are required to provide housing, has further limited options for full-time workers.

Many employers have bought property to provide housing for seasonal workers, but that leaves fewer options for those seeking a year-round home.

“There are lots of employers that are snatching up houses for their workers, which is good, but also limiting,” Goode said.

As tourist growth triggered an increase in seasonal employment, it also increased demand for hotel rooms and other lodging, but that did not lead to new construction.

Instead, many homes and cottages that otherwise would have been vacant or available for rent have been turned into tourist rentals, such as Airbnbs, further narrowing the year-round housing pool.

Housing prices across Door County surpass what over half the residents can afford

In 2018, the average price for a home in northern Door County was $376,568, according to the report. Excluding waterfront homes, the average price was $268,137.

Southern Door County is less expensive, with an average non-waterfront house price of $195,014, and Sturgeon Bay is even less at $161,146.

Countywide, the median selling price of homes in the county this year was $270,000 as of the end of April. At that price, the typical mortgage payment, including taxes and insurance, would be about $1,600.

The U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development considers households “cost-burdened” when over 30% of their income goes toward housing, leaving little room for basic necessities and medical care.

Under that guideline, a household that earns the county’s median annual income of $56,500 could afford to spend $1,412 per month on housing, making a home purchase tight, but manageable.

But home prices put ownership out of reach of many residents, including entry-level patrol officers, registered nurses and elementary school teachers, according to the Housing Door County presentation.

An entry-level teacher, for instance, makes about $36,000 annually, allowing for a monthly housing budget, as recommended, of $900 a month.

That teacher would still be better off than the roughly one-third of working households in Door County that make just enough money to be above the federal poverty level, but not quite to a level that United Way calls “household stability.” For Door County, that’s about 31% of the population, according to a United Way of Wisconsin report.

These ALICE households — Asset Limited, Income Constrained and Employed — live on a survival budget and can’t comfortably afford necessities, such as housing, food, health care, transportation, child care and technology.

For these and other households, homeownership is particularly difficult, but finding affordable apartments and rentals also can be challenging due to a limited supply.

At the start of June, there was just one single-bedroom apartment listed as available in the county on apartmentfinder.com, located in Sturgeon Bay with a minimum rent of $1,170 a month. One two-bedroom apartment was available in Sister Bay with a minimum rent of $1,325.

Rent in the county often starts at $800 a month for a one-bedroom apartment, on the high end of the $500-to-$900 range the housing report identifies as affordable.

A single adult making an ALICE minimum income of $19,956 can afford to spend $499 per month on housing in Door County and not be cost burdened, and a single adult making a minimum wage income can afford to spend $377 per month.

The lack of less expensive rental options reflects the hesitance of developers and construction companies to build affordable housing projects because they often can’t make enough money to cover construction costs, Funkhouser said.

“The challenges go back to developers thinking not just, ‘How am I going to make money,’ but ‘How am I going to break even?’” she said.

In time, the housing market’s problems will eventually drive away the year-round workforce and slow the county’s economic activity, according to the report.

“I understand our tourist industry is what feeds us, but what people need to remember is that if you want to attract a workforce to keep up with your growing industry, they need a place to live and an affordable and decent home,” Johnson said.

Change coming as housing solutions develop

In the past two years, the county and housing organizations have begun to implement some of the recommendations included in the 2019 report.

According to Goode, construction projects in the county’s future include Habitat for Humanity houses; 45 affordable rental homes near the Northern Door Children’s Center in Sister Bay, which received a WHEDA tax credit award; and the West Side School project, which is funded by community development grant dollars and will consist of 15 units, with eight or nine of them being affordable.

Currently, the county’s Land Use Services Department is working on amendments to zoning regulations to encourage more affordable housing projects, Goode said.

Allowing smaller lot sizes, taller structures and fewer public hearings could make it easier to find land and build more multi-family units, the report suggested.

The zoning amendments would affect Sturgeon Bay and nine of the county’s 14 towns, and would act as a model for the remaining towns and villages, Goode said.

In addition to her office’s regular duties, Goode is also involved in some of the county’s upcoming initiatives.

The Wisconsin Housing and Economic Development Authority chose Door County, Marinette County and two counties on Lake Superior for a pilot program that aims to develop local solutions to the lack of affordable workforce housing in rural areas.

The initiative started in December and has completed the first phase, an analysis of the issues holding back development of affordable housing, including financing, land use and homeowners’ negative perceptions of affordable housing.

Another ongoing project is a University of Wisconsin- Madison program, UniverCity, comprising around 150 students in three classes studying real estate. The students were tasked with studying properties in Egg Harbor and coming up with project ideas, but the scope has since expanded into the other northern areas and Sturgeon Bay, with a focus on affordable housing.

“That project will be interesting because it will show what these properties could look like,” Goode said.

The program has one more year to complete, and the county can use the final draft to discuss ideas for the future, but isn’t required to adopt any of them.

Goode is also a board member for the Door County Housing Partnership, a non-profit housing trust that helps make housing perpetually affordable for working families.

“The trust acquires land and continues to own it so it can control who moves in and how much it’ll cost, based on the affordable price for families,” she said.

The trust pays the cost difference to builders, and the families can turn around and sell the house after they have some home equity. They can then use this money to live on their own more comfortably.

However, a lack of public support remains a major challenge in the effort to develop more affordable housing in the county.

Affordable housing efforts across the nation meet “not in my backyard” opposition, according to the report, and Door County is no different, with neighbors pushing back against proposed developments.

Concerns over these efforts have ranged from how the county will finance the projects to whether the county needs to develop housing for lower-income families, the latter of which often stems from confusion over what “affordable” and “workforce” mean.

“Low income doesn’t mean trailer park, and low income doesn’t mean we are trash,” Johnson said. “We are the ones you rely on to make your time up here enjoyable.”

Wisconsin Watch is a nonprofit newsroom that focuses on government integrity and quality of life issues. Sign up for our newsletter for more stories and updates straight to your inbox.