It’s a hot June day and Pennsylvania Human Services Secretary Teresa Miller is in a dark blue suit facing a flaming metal-and-masonry hearth in a Homewood parking lot. A group of culinary trainees from Hazelwood’s Community Kitchen are showing her how they make pizza in the oven, which was built by apprentice welders and masons.

Both of the non-profit organizations in this joint demonstration — Culinary Kitchen and the Trade Institute of Pittsburgh — provide tuition-free, 12- week workforce training to those facing employment challenges such as conviction records, lack of education or training, substance abuse, and/or family financial challenges. Both are funded by federal dollars and revenue generated through sales of goods and services performed by program trainees. And both, in Miller’s view, are “changing lives one person at a time and providing a really valuable service to the Commonwealth by helping the individuals that we serve to gain living wage jobs and, ultimately, transition off of public assistance.”

Community Kitchen occupies Hazelwood’s former G.C. Murphy Company store on Second Avenue, a few blocks from where the hulking exoskeleton of Jones & Laughlin Steel Mill 19 is being redeveloped into a light industrial and office complex.

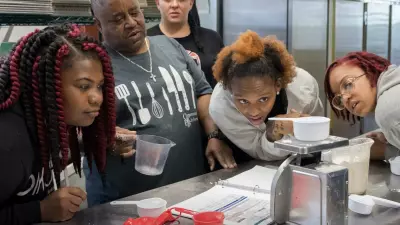

Inside its new kitchens, culinary trainees help fulfill contracts for catering and school lunches. There’s also a pay-what-you-can “showcase lunch” for the public every Thursday, and a dinner series featuring guest chefs from local restaurants. Someday there will be a full-service café, which will resemble the country’s first enterprise of this type, Washington’s DC Central Kitchen, founded in 1989.

Community Kitchen founder and Executive Director Jen Flanagan saw a local need for its services in 2013.

“Food service is an industry with low barriers to entry, meaning no advanced degree is required, there are openings at various skill levels, there are a range of shifts, which can accommodate people with kids or other life situations; and it’s an industry in which merit- based advancement is often how people get promoted. You show up, you work hard, you can get a promotion.”

As a partner in the commonwealth’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, half of the $10,000 per- student cost for training is covered by federal funds and the rest is covered by Community Kitchen, a nonprofit. Cost is calculated to include staff time, earning materials (including culinary knife kits, shoes, and bus passes) and follow-up services like job placement and retention counseling.

“We know the outcomes for these programs are pretty amazing,” Miller said.

According to Community Kitchen, their training program has a 92 percent placement rate for graduates upon completion and an 85 percent job retention rate after 12 months.

“Those are the tangible benefits for the state,” she continues, “We really want to see these programs expand, because they’re doing a great job of getting people to work.”

Job growth in the food preparation and serving industries could increase about 12 percent nationwide by 2027, according to the Pittsburgh-based workforce development organization Partner4Work. Community Kitchen graduates have the potential to take their training and use it to score one of almost 15 million jobs.

“It’s an industry in which merit-based advancement is often how people get promoted. You show up, you work hard, you can get a promotion.”

Less than five miles away, at the David L. Lawrence Convention Center in downtown Pittsburgh, three graduates of Community Kitchen’s culinary program are at work over a baby blue conveyor belt. They’re prepping 400 salmon entrées for a private luncheon.

Prepping the meals is easy for Executive Chef Dominique Metcalfe and her team in the institutional kitchen. During 2009’s G20 Summit in Pittsburgh, she oversaw an operation feeding more than 4,000 visitors daily at the convention center.

Sporting crisp white coats and black head covers, Sierra Moore and Marlyn Williams chat across a large metal tray, as they alternately scoop green creamed spinach onto white plates.

“Chef Dom” walks between them, exchanging a full, steaming tray for the empty one, mouthing something to the others. Simultaneously, the three women burst into laughter, as they keep dipping their scoops, sending plates down the line for the herb-roasted potatoes, bright orange young steamed carrots, and thick pink salmon filets to complete the composition.

When the dirty plates come back upstairs after lunch, they’ll be loaded onto more conveyor belts racks inside a maze of shining industrial dishwashers run by Orlando Reeves, a tall, fit, and serious coworker whom Sierra and Marlyn jokingly refer to as “The Grinch.”

While it reads a bit like a scene from a school cafeteria, these are all union jobs boasting some of the highest starting food service wages in the city: Dishwashers start at $15.15, prep cooks at $15.55; line cook 1 earns $16.80 and line cook 2 gets $17.80.

Once working, employees receive annual raises each November and can apply for promotions through the testing protocol of Unite Here Local 57. That union represents hospitality workers in the hotel, gaming, food service, airport, textile, manufacturing, distribution, laundry, and transportation industries, including many Downtown hotels, PNC Park, and PPG Arena, as well as regional casinos

and racetracks.

David L. Lawrence Convention Center’s food services are run by Levy Restaurants, a 40-year-old Chicago company which today has 40,000 employees in 200 locations, mostly sports stadiums and convention centers. In 2000, Levy was acquired by Compass Group USA, which claims to be the largest ‘food service and support services provider” in the country, with revenues of $18.6 billion in 2018. Employees like Community Kitchen graduates Moore, Williams, and Reeves, thus, have ample opportunity to move around and up into other positions in a national market.

Metcalfe hired Moore, Williams, and Reeves straight from their Culinary Kitchen graduations. Prior to her June 2019 course completion, Williams had only home cooking experience, honed while raising three young children; Moore came into the program in 2018 with some previous restaurant and home- catering work experience, but no formal training; and Reeves, in 2016, came to the program, having learned to bake and cook when he was assigned kitchen duty inside the SCI-Somerset, where was he was serving a sentence for robbery. He eventually became the prison’s head cook.

It was back in 2016, when a career services counselor reached out to help place Reeves in a job, that Chef Dom first became aware of Community Kitchen.

“Normally we do background checks, so I asked my boss if I could just bring him in [despite his record] because he has a great work ethic,” she said. “He was all dressed up for his interview. And he’s not the first person we’ve hired who had a background like that. We do a little checking, but as a big corporation, we give everyone a 90-day probationary period, so why not just try? Everyone deserves a chance.”

Marlyn Williams works weekends as a security guard in the Frick Building Downtown. She’s paid $12.35 per hour, but that’s not enough to support her three school-age children. Even though she has a bachelor’s degree in psychology, she was having a hard time finding a job working only during school hours.

Also a working mother and her family’s chief breadwinner, Metcalfe said the two met when she returned to Community Kitchen this past spring to help students cook a showcase dinner event.

“She was working beside me rolling out gnocchi, talking about her home life. When she told me she could only work ten to two, and I said I’d hire her, she gave me the biggest hug,” Metcalfe said. “It warms your heart because you don’t know what’s going on in someone’s personal life, but it was like we were meant to be there [together] at that time, so she could work here.”

“They’re here to work and be a part of the team. They don’t just show up. They have heart and instinct.”

Williams still works the weekend security job—which Metcalfe encouraged her to keep—but her starting wage as a prep cook is $15.55 per hour when she works at the convention center on weekdays.

If Williams was underemployed, Sierra Moore is over employed. She works a full-time overnight job caring for developmentally disabled adults in a personal care home facility, where she cooks, cleans, does laundry, assists with medications, and runs errands for her charges. When scheduled to work both jobs, she stays overnight by herself at the residence and then returns home the next day to get a few hours rest before coming to work in the kitchen at the convention center.

After four years at her home healthcare job, she earns only $11.75 per hour — $3.80 less than the $15.55 she makes in Metcalfe’s kitchen after only one year. She’d rather work only in the kitchen and dreams of someday owning and operating her own business: a food truck with her youngest daughter, age 11.

Metcalfe’s co-executive chef for Levy, Todd Yeckel, chimes in about his Culinary Kitchen-trained employees’ work habits:

“They know the basics and they pay attention. They complete their jobs in a timely manner,” he said. “It’s a pleasure to have people who pay attention and learn and expedite the way you expect. They’re here to work and be a part of the team. They don’t just show up. They have heart and instinct.”

The main challenge going forward for making a bridge between workers like Moore, Williams, and Reeves and good jobs like those at Levy, is expanding the reach of education and training partnership programs like Community Kitchen, Miller said.

“It’s a small program right now. There’s about 309 people served by 14 programs statewide and they’re trying to meet a goal of having 30 partnerships by the end of the year.”

She said some mandated government-run programs attempt to simply place people into jobs.

“What we have to do is fix our intake process, because when we bring people in, we talk to them about getting to work but we’re not necessarily having a conversation with them about ‘what is it that you want to do?’ and ‘let’s talk long term about in three to five years, where do you want to be?’”

“A lot of the population we serve is anxious to work,” she said. “It’s about having a different conversation.”

Or, to put the Community Kitchen experience into Sierra Moore’s words: “I got awareness, good skills, and proper terminology. Everything they taught, I use and I needed. I knew how to cook, but they gave me the right tools to proceed professionally versus just being a cook at home.”

And the best part of Sierra’s new professional life in the kitchen?

“I like the real freedom of being able to learn. And I just love to see the happiness once people taste your food, to see their faces light up because they were pleased with my meal. That’s my end goal.”