“Right now I wish we were back in Iraq,” yelled my friend and photographer Nish Nalbandian as our motorcycles idled in Nashville’s seemingly endless gridlock.

I was in the middle of my own full-throated gripe when the driver next to us started honking his horn for our attention.

“Hey guys,” yelled Bnyad Sharef, a smiling, young Iraqi Kurdish man we’d met the other day. The three of us laughed at the circumstance of our reunion and swapped complaints about the traffic till the light turned and we parted ways.

When we pulled over for gas, Nish and I pondered the near-freakish serendipity of crossing paths with Bnyad at the very moment we were waxing nostalgic for Iraq.

“No one is going to believe that just happened,” I told him.

We’d been reminiscing about Iraq for good reason. Nish and I worked there together several times over the last few years covering the war and were in Nashville to report a story about the Kurdish community, many of whom hail from Iraq.

An estimated 15,000 Kurds, an ethnic group whose population lives in Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and Syria, have made Nashville their home, making it the largest Kurdish community in the United States.

The first Kurds came to Tennessee in the late ’70s and early ’80s following a failed independence attempt and to escape persecution at the hands of former Iraqi leader and tyrant Saddam Hussein. A decade later, more fled Hussein’s wrath, this time genocidal chemical attacks that killed tens of thousands of Kurds.

The most recent Kurdish arrivals were escaping the horrors brought on by the Islamic State in both Iraq and Syria, many of them traveling through Turkey, then Europe, before settling in Postindustrial America.

Nish and I have spent much time in the company of Kurds in their native Middle East and Turkey, where they are the world’s largest ethnic group — an estimated 30 million or so — without a nation of their own.

We’ve heard many firsthand accounts from Kurds who endured these atrocities, yet remained resilient in the face of so much suffering. We rode into Nashville to interview those who left family and loved ones behind to brave uncertainty in a strange land and create better lives for themselves and their children.

Our last reporting assignment together in Iraq was also done by motorcycle, an old Russian bike with a sidecar that we bought in Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city.

Much of the city had been destroyed in the fight between the Islamic State and Iraqi forces and their allies, including the Kurdish militia known as “Peshmerga,” which roughly translates to “those who face death” in the defense of the Kurdish way of life.

We rode the Russian bike along the war-pocked roads linking Mosul and Erbil, which serves as the capital of Iraq’s Kurdistan region. Our moto mission in Iraq wouldn’t have been possible without the help of our friend and translator Sangar, an Iraqi Kurd who lived in Mosul until the fighting forced him and his family to flee.

So it only seemed appropriate that we saddled up on motorcycles again to learn about the new lives Kurds have made for themselves in a city most folks associate with country music and honky-tonkin’ good times.

An estimated 15,000 Kurds, an ethnic group whose population lives in Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and Syria, have made Nashville their home, making it the largest Kurdish community in the United States.

But this trip was different. Instead of riding a rusty, bullet-hole-ridden bike with faulty brakes through an active warzone, we were astride a couple of brand new bikes loaned to us by Yamaha and equipped with all the requisite bells and whistles needed to make our Nashville journey a joyride in comparison.

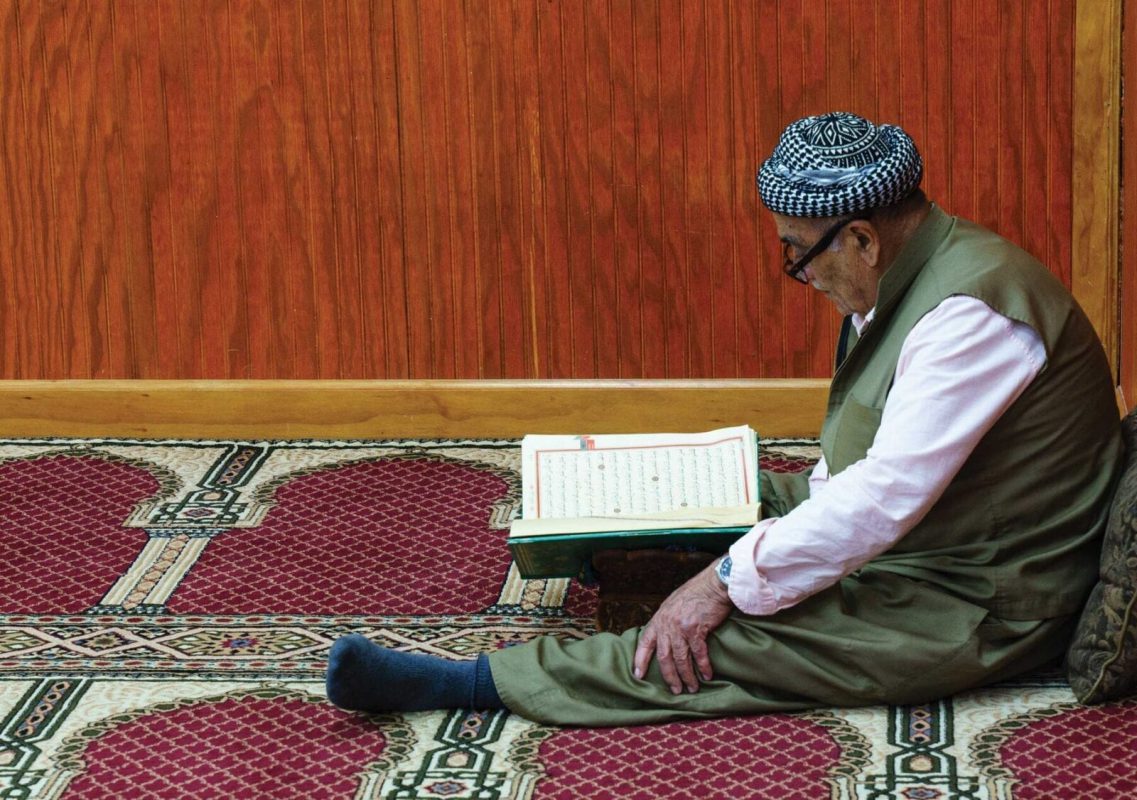

We spent our first day on the bikes cruising from neighboring Georgia into verdant, mountainous Middle Tennessee. After settling in Nashville, we struck out for the first stop on our journey to the heart of Nashville’s Kurdish community: the Salahadeen Center, a mostly Kurdish mosque that also caters to Muslims of all stripes located in a neighborhood known as “Little Kurdistan.”

There we met with Nawzad Hawrami, the center’s manager. Hawrami is a soft-spoken man who conveyed a powerful passion for the Kurdish community

in Nashville.

“Our mission here (at the Salahadeen Center) is to protect our community, culture, and language,” said Hawrami while showing us where the devoted pray five times a day. Nearby is a center where Kurdish youth in Nashville can improve their native language skills and learn the rich, oft-troubled history of their people.

That’s not to say the Kurdish community hasn’t experienced their share of trouble in the States. A few years ago, the Kurdish community was forced to deal with an American dilemma that arrived on their doorstep: some of their youth had formed a Kurdish gang and gotten into trouble with the law.

“During that time, we had a problem with our children,” he said. “But we worked with the police and community to fix it.”

Hawrami noted how it had been several years since those troubled times and that most of the Kurdish youth appeared to be on the straight and narrow.

The mosque’s imam, or religious leader, Salah Othman, nodded in agreement.

“You have to realize that kids here are growing up in a different culture,” Othman told us before afternoon prayers at the mosque, acknowledging the ongoing challenges Kurdish parents face in raising children in America.

“Sometimes there is a gap between the parents and kids … If we don’t have communication, our problem starts there.”

A young Kurdish man named “Hardy,” who asked that I not divulge his last name because of his previous work as an interpreter for U.S. forces in Iraq, said he’s preparing for those challenges with his four young children, all born in the United States.

Many interpreters from both the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have sought asylum in America for fear of being beaten, even killed, by extremist groups for working with U.S. troops.

“Most (Kurdish) parents want their kids to keep their culture but be good citizens in this country,” said Hardy. “We want the Kurdish people to think of this place (Nashville) as

their home.”

The three of us and a handful of others from the Salahadeen Center continued our conversation at a nearby restaurant where we dined on kabobs and other assorted delicacies from the region, the first of many times we were fed to the point of bursting by Nashvillian Kurds, as is customary in their homeland as well. Nish and I have often remarked at how every time we go to Iraq, we end up gaining a few pounds due to Kurdish hospitality.

After lunch, we asked Hawrami if he knew of any Kurds in Nashville who also rode motorcycles. We’d been trying to find someone in the community to ride with us for weeks before our arrival with no luck. He made a few phone calls, then produced a slip of paper with the phone number of a man named “Zari” who he said was eager to ride with us.

I called Zari, but no answer. After leaving him a message, we mounted our motorcycles knowing we had a bevy of new Kurdish acquaintances eager to help us tell their story.

Twelve-year-old Shad Sharef loves astronomy, acting and watching Korean TV dramas so much she told me she plans to study the language.

Her older sister Yad, 19, laughed at her sister’s pop-culture obsessions, though she admitted she also liked the Korean shows, as well as Turkish soap operas.

They seem typical in many ways, though their lives have been fraught with perils far greater than those of most kids their age.

Along with their brother Bnyad, 22, they came to the United States two years ago with their parents to escape the violence that had consumed northern Iraq since the Islamic State took over large swaths of the country.

“We sold everything, our house, cars, and quit our jobs to come here,” Fuad Suleman told us one evening before dinner at his home in southern Nashville.

Fuad, along with his children and wife Arazoo Ibrahim, chose Nashville as their new home because of its large Kurdish population, and like many Kurds, said the forested mountains and mild winters of Middle Tennessee reminded them

of Kurdistan.

I could see why. We rode miles of backcountry roads before dinner that reminded me of the tree-covered slopes of Iraqi Kurdistan I’d come to know from years spent in the region.

However, theirs was an American immigration story that almost ended before it began.

As they were about to embark on the last leg of their journey to the U.S., the family hit a political roadblock. In 2017, the Trump administration instituted its majority-Muslim-country travel ban, including those from Iraq, temporarily halting their progress in Cairo.

Fuad and his family were forced to return to their hometown of Erbil in Iraqi Kurdistan until the ban was overturned. Only then would they finally realize their ambitions of coming to America and settling in Nashville.

“There were hundreds of people in the airport, holding signs welcoming us and chanting ‘Welcome Home,’” Fuad told us over dinner at his home, a selection of Kurdish delicacies including “dolma,” a variety of vegetable stuffed with meats and rice, followed by an assortment of homemade sweets, all prepared by Arazoo with the girls’ help.

Since their arrival in Nashville, Fuad, 53, has worked a series of jobs, most of which didn’t capitalize on his three university degrees.

“It was difficult at first finding a good job so I took what survival work I could including in a warehouse,” he said.

Recently he found a more satisfying, lucrative position working in the office of Lyft in Nashville, where he works with the ride-share company’s bilingual drivers, a position more suited to his education and language skills including Arabic, Kurdish, English, and Farsi.

Bnyad is hopeful he’ll have better career opportunities than his friends back at home in Erbil, where even those with degrees ideally suited to the region’s oil-rich industry can’t find work.

“I have friends there who are stuck and can’t find a job, friends with petroleum engineering degrees who don’t have work,” he said.

Bnyad studies computer programming as a local university and like his older sister Yad, who also shares a passion for computers, hopes to find work upon graduation in Nashville’s growing IT sector.

Though Arazoo is still learning English, she also works as a caterer, having started her own business, which she playfully calls “Zoo’s Kitchen.”

Her children laughed when I repeated the name, saying it sounds like their mother prepares exotic animals instead of traditional Kurdish fare.

Arazoo uses her cooking as a way to educate those that book her about the different dishes she prepares, the history of the Kurdish people and her own and her family’s journey to America.

“We cater events people always ask about the origins of the dishes and the people who prepare them,” she said.

While many folks welcomed Fuad and his family in Nashville, they have also experienced their share of discrimination aimed at immigrants such as themselves, particularly those who are Muslim.

During a recent event known in Nashville as Immigrant & Refugee Day on the Hill, the immigrant community converged on the state Capitol to share their stories and lobby lawmakers. At that event, Fuad said, some protesters said: “We don’t want you here.”

“Or they say ‘We want you here because you are legal. We don’t want illegals,’” he recalled, shaking his head.

“That’s not a good argument because my family and I were legal, then made illegal (due to the temporary Muslim ban imposed by the Trump administration).”

Our discussion for the rest of the evening centered on the festering resentment for immigrant communities in some parts of Postindustrial America and what can be done to rectify it. Unfortunately, none of us could formulate a ready answer to this growing dilemma.

Before saddling up and riding off from their home, we asked Bnyad to help us track down Zari, who still hasn’t given us a definitive date to join us for a motorcycle ride. Bnyad said he’d see what he could do to draw the elusive Kurdish rider out of the woodwork and onto the road.

When we weren’t enjoying the company of Nashville’s Kurdish community, or trying to track down Zari, Nish and I took in some of the more traditional tourist trappings of the Music City.

Downtown’s honky-tonk district along Broadway is where tourists try on cowboy boots and hats before bellying up to numerous bars where live performers chasing their Nashville dreams of country music stardom belt out the classics of the genre.

Later we rode out of the city to escape the midday swelter and headed for a nearby lake, where we took a dip with a curiously unafraid flock of ducklings, though we kept a respectful distance from the youngsters so as to not invoke the ire of their protective parents swimming nearby.

After drying off, I received a text from Zari, the first of many back and forth promising us he’ll meet for a ride though his work schedule these days is particularly “crazy.”

“Sorry, brother. I’m busy at work now,” he wrote me, assuring that he’d make the time to link up with us before we left town.

While exploring Nashville, we noticed that the Kurdish community wasn’t the only prominent immigrant group to call Music City home. We sped past Vietnamese, Salvadoran, and Mexican restaurants. We chose one area-favorite Mexican joint to meet Kurdish immigrant and former U.S. Army translator Mohammed Berwari.

Talking over burritos and tacos, Berwari, who goes by “Moe,” was less interested in rehashing his front-line exploits with American troops and more enthused about his life in Nashville, where he’s lived for the last few years.

His is seemingly the prototypical attitude of the aspiring immigrant, albeit one with a slight Tennessee drawl: “Here, if you work hard, you are going to make money,” he said while recalling his various jobs including a stint as a manager at Taco Bell and a towel boy at a YMCA.

But his opinions took a surprising turn when he expressed admiration and support for President Donald Trump, who has taken a hard-line stance to dramatically limit the number of immigrants coming to the United States.

“You’ve got to have borders and there has to be a better process for that (immigration),” said Berwari, adding that he liked Trump’s “tough stance” on Iran.

Aspects of Trump’s rhetoric didn’t, however, resonate with him. “Trump didn’t make America great— it’s been great since the (first) Fourth of July,” he said with the zeal of a new citizen, which Berwari officially became earlier this year following his swearing-in ceremony.

Berwari’s first order of business after becoming an American? He said he registered to vote.

After several days of riding around Nashville visiting with various Kurds, we felt like we were getting a handle on the community.

Some we spoke with expressed the importance of passing along the Kurdish traditions and language to the younger generations, particularly those born in the United States. Others, often younger Kurds, appeared to prioritize Americana over the ways of a world they either left behind or never knew.

To better understand this diverse community, our story needed historical context, which is why we rode over to Tennessee State University one morning to chat with Kurdish professor Kirmanj Gundi, an administrator in the school’s education department.

Gundi, who is working on a book about Kurdish history dating back to ancient Kurdistan, spoke to us of his homeland’s history starting at the end of World War I and the fall of the Ottoman Empire.

The Kurdish people were promised an independent state that never materialized and since then have been systematically marginalized and persecuted by numerous leaders of the nations they call home.

By 1975, a Kurdish revolution attempt aimed at carving an autonomous Kurdistan out of northern Iraq had failed, precipitating the first wave of Kurdish immigration to the United States.

Among those who arrived here was a young Gundi and his family. Now 58, he recalls those difficult early days.

“We arrived in Nashville on Aug. 24, 1977,” he noted in his precise recollection of his earlier days in America. “And the very next day I was working at a TGI Fridays in the kitchen washing dishes.”

Just a teenager, he didn’t speak English when he arrived and spent the next two years learning the language and struggling. “I could barely keep my head above water,” he recalled.

Dark times descended on the Kurdish community in Iraq. The Hussein regime used chemical weapons to kill 50,000 to 180,000 Kurds.

Meanwhile back in Iraq, Saddam Hussein came to power in 1979 and began ramping up the pressure on the Kurdish community there.

Less than a decade later, Gundi was a Tennessee State University graduate with a degree in computer science and a minor in mathematics. He accepted a position teaching at a local high school.

Dark times descended on the Kurdish community in Iraq. The Hussein regime used chemical weapons to kill 50,000 to 180,000 Kurds.

The genocide prompted another exodus from Iraqi Kurdistan to Nashville.

“There was a huge wave of Kurdish migrants to Europe and the United States” following the massacre known as the Anfal Campaign at the end of the Iran-Iraq war, Gundi said.

This represented the largest wave to date of Kurdish migrants to the region. Then in 2012-13, when the Islamic State began taking control of swaths of Syria and Iraq, the most recent wave of Kurds came to Nashville. The latest arrivals have had an immediate impact on their community, he said, noting how hard they have worked to make a go of life in America.

“Fortunately a lot of people in our community are doing very well,” said Gundi with an air of pride. “I’ve never heard of a Kurd (in Nashville) who can’t make a living.”

We thanked Gundi for his time and insights, then rolled out of campus looking for some open road to ride. We barrelled down highways and backroads for the rest of the day, enjoying the fine Tennessee summer.

That night, while going over my notes, I received a text from Zari:

“I’m really sorry buddy but unfortunately this week has been really crazy for me.”

I asked him to make time for us whenever he could, even if for only 10 minutes.

Zari said he’d see what he could do, but couldn’t promise anything.

“When people sacrifice their lives for you, you have to pay them back.”

We spent our last few days in Nashville listening to Kurdish folks tell us their stories.

One of our favorites was hair salon owner and stylist Abdulwahab Omer, who spoke of his time translating for American soldiers while giving Nish a much-needed haircut.

Omer recalled harrowing times under fire with the troops, but said he’d do it again if his services were needed.

“If they (U.S. forces in Iraq) need my help, I’m not going to hesitate. I’ll do it again,” said Omer while shaving Nish’s scraggly goatee.

“When people sacrifice their lives for you, you have to pay them back.”

We timed our departure from Nashville to coincide with a celebration in Little Kurdistan of a mural painted by a trio of artists depicting life in Erbil.

The pastel-colored, building-length homage to life in the de facto capital of Kurdistan was a loving tribute to the history and heritage of the Kurdish people. In it, Kurds in traditional dress enjoy a meal in the shadow of the hilltop citadel in Erbil and the nearby marketplace.

“We’ve eaten at that table,” Nish remarked, pointing to a couple of Kurdish men depicted in the foreground of the mural eating near the historic structures we’ve come to know so well while reporting from Iraq.

The three artists who collaborated on the mural told us their respective stories. Rafif al Saleh is an artist and Arab from Iraq who drew Kurdish calligraphy in the mural.

“Words bring us one step closer to understanding this culture,” she said while translating the collection of words and poems, some of which take the form of birds circling over a group of Kurds talking. “The birds are carrying away what they are saying,” she said while explaining her artistic choices.

Nabeel al Yousuf, an artist who hails from Mosul and is still learning English, told me through a translator that he “cried so much” at the destruction of his hometown during the war with the Islamic State. But working on the mural in his adopted city of Nashville gave him hope for the future of Iraq. “It just felt so good to work on this project with Rafif and Tony,” he said.

The “Tony” of which Nabeel spoke is Tony Sobota, a Nashville local and artist who, though he never visited the area depicted in the mural, said he felt so embraced by the Kurdish community while working on the mural that he’s been given the nickname “Tony Kurd.”

Many of the people we’d met over the past week attended the mural’s unveiling, including our new friends from the Salahadeen Center and others.

“Events like this help us introduce the Kurdish community to everyone else,” said Salahadeen Center manager Nawzad Hawrami.

The mural’s official unveiling marked the near-perfect completion of our assignment, except for the one component we’d missed: our motorcycle ride with the now-seemingly phantom Zari.

But just as we were about to take off, my phone buzzed with a message from Zari.

“I’m about to come say hey and ride down there.”

Not sure whether Zari was really on his way, we decided to wait another 20 minutes before writing him off.

Then, just when we thought him a no-show, we heard the sound of a high-pitched racing bike grow louder as it approached, followed by the sight of a rider sporting a silver-decaled helmet topped with a GoPro.

Then, just when we thought him a no-show, we heard the sound of a high-pitched racing bike grow louder as it approached, followed by the sight of a rider sporting a silver-decaled helmet topped with a GoPro.

Removing his helmet to reveal a floppy mop of hair tied in a front-mounted ponytail, Zari Mouzoury, 23, offered apologies for making us wait until the last minute for our meeting.

He spoke of his arrival in Nashville at 13 and the culture shock that ensued.

“I didn’t speak English, not a single word, so other kids made fun of me,” he recalled.

A decade later, he’s a college graduate who works for a judge at a local courthouse, with an expert command of the English language, which he peppers with “bros” and “mans” like any 20-something rider of a high-speed bike like his might.

Alas, Zari couldn’t stay long.

“Brother, I wish I could ride with you, but I have to go,” he said after we grabbed a few photos of him racing up and down the street and glamming for the camera.

He promised he’ll have more time to ride with us the next time we’re in Nashville, giving Nish and I another reason, among many, for our planned return.