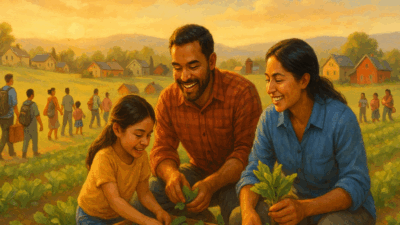

Once powering communities, former industrial sites in Pennsylvania and Alabama now draw history-loving tourists.

In Birmingham, Ala., the Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark tells the story of what was once the largest manufacturer of pig iron in the world, looking much today as it did a century ago. Near Philadelphia, the National Iron and Steel Heritage Museum collects and exhibits historical materials related to the coal and steel industry. Other sites in Pennsylvania — Cambria Ironworks in Johnstown and Carrie Blast Furnaces just outside of Pittsburgh — also are National Historic Landmarks.

Jim Kapusta is one of many people around the country who could tell stories about working in steel mills to tourists who visit their former workplaces.

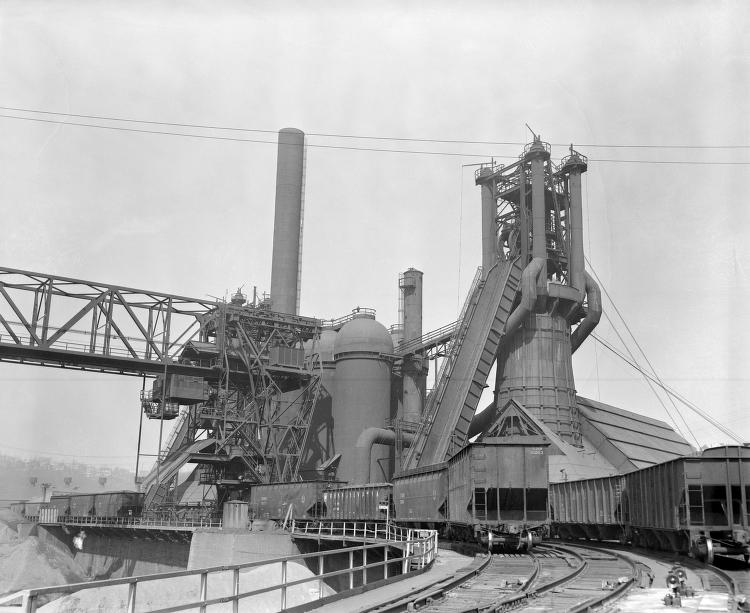

On a recent weekend, he reminisced to his tour group about the grueling active years of the Carrie Blast Furnaces, where he and his coworkers put out more than 1,000 tons of pig iron a day during the steel industry’s post-World War II glory days.

Kapusta, who worked at the suburban Pittsburgh mill from 1964 to 1982, still has a piece of metal lodged in his right thigh from an injury at the mill.

He remembered how the amateur furnace men and electricians wore orange hats and how employees’ green jackets would smolder when they got too close to the flames.

“If you didn’t get hurt, you were hiding,” Kapusta, a tour guide, told his audience.

The metal at Carrie Blast Furnaces has long gone cold since closing in 1978, and the steel era in Pittsburgh is over.

Carrie opened for tours in 2005 after furnaces No. 6 and No. 7 were preserved. Some 60 miles east of Pittsburgh, is the Cambria Ironworks in Johnstown.

In Alabama, Sloss Furnaces transformed iron ore, coke and limestone into iron starting in 1880. The mill closed in 1971 but reopened as a museum operated by the City of Birmingham and Sloss Furnaces Foundation in 1983. At Sloss, visitors explore such features as steam-powered blowers, and blower engines.

The city of Birmingham – rich in iron, limestone, and coal – was built to capitalize on these resources, said Tyler Malugani, Sloss education coordinator. By 1900, there were close to 30 furnaces in the Birmingham area, but the region has largely moved on from its industrial past.

“Since Birmingham was made as an iron town and you don’t see much of that history anymore,” Malugani said. “Having a site like that can help remind people of why Birmingham exists.”

Today, Sloss gives people “the opportunity to learn about that history … and walk right next to it, right where the men were working,” he said.

Indeed, at these sites, people can learn about the industrial past of a region, seeing the sites and walking around instead of simply reading about them, said Ron Baraff, director of historic resources and facilities for Rivers of Steel, which owns and operates Carrie.

“It’s more than just the physical structures themselves; it is the essence of the place,” Baraff said. “It has deep meaning … not just for us, but for the country. What happened here changed the world. All of the mills here … really allowed for America’s 20th century.”

Preserving a steel mill and converting it to a historic site is rare, as most mills are leveled once they close, and the metal is scrapped, said Scott Huston. He is president and director of the National Iron and Steel Heritage Museum in Coatesville, Pa., near Philadelphia.

“They kind of languish for a while because they are typically underutilized property,” he said. “Steel companies tend to eat themselves.”

Another possible destiny for a former mill is for the site to be cleaned up and redeveloped into something commercial that maintains vestiges of the industrial past. An example is the Waterfront shopping area of suburban Pittsburgh, where smokestacks from the Homestead mill stand near the AMC movie theatres.

In Bethlehem, Pa., Bethlehem Steel was converted into the 10-acre SteelStacks campus, which hosts concerts, festivals and other community events and celebrations. At SteelStacks, five of the actual “stacks” — blast furnaces from the steel mill — remain.

At Carrie, though the site that straddles the communities of Swissvale and Rankin is primarily a preserved historical spot, the owners also use it for events and attractions such as weddings, artist installations, and car shows. During the COVID-19 quarantine, Carrie has even turned into a makeshift drive-in theater, where socially distanced people watch movies on a courtyard screen.

The Coatesville museum site is a hybrid of history and a “hot spot” active mill, since part of Lukens Steel Co. is still operating there. The museum — which focuses on the science of steelmaking more than the history — acquired the rest of the buildings, including houses.

Historical mills offer excellent learning opportunities for students on field trips, and for adult history buffs, Huston said.

Those mills that are renovated for commercial use, like in Bethlehem, can become economic engines for those regions.

“People want to go where history happened,” Huston said.

Indeed, at these sites, people can learn about the industrial past of a region, seeing the sites and walking around instead of simply reading about them, said Ron Baraff, director of historic resources and facilities for Rivers of Steel, which owns and operates Carrie.

“It’s more than just the physical structures themselves; it is the essence of the place,” Baraff said. “It has deep meaning … not just for us, but for the country. What happened here changed the world. All of the mills here … really allowed for America’s 20th century.”

Preserving a steel mill and converting it to a historic site is rare, as most mills are leveled once they close, and the metal is scrapped, said Scott Huston. He is president and director of the National Iron and Steel Heritage Museum in Coatesville, Pa., near Philadelphia.

“They kind of languish for a while because they are typically underutilized property,” he said. “Steel companies tend to eat themselves.”

Another possible destiny for a former mill is for the site to be cleaned up and redeveloped into something commercial that maintains vestiges of the industrial past. An example is the Waterfront shopping area of suburban Pittsburgh, where smokestacks from the Homestead mill stand near the AMC movie theatres.

In Bethlehem, Pa., Bethlehem Steel was converted into the 10-acre SteelStacks campus, which hosts concerts, festivals and other community events and celebrations. At SteelStacks, five of the actual “stacks” — blast furnaces from the steel mill — remain.

At Carrie, though the site that straddles the communities of Swissvale and Rankin is primarily a preserved historical spot, the owners also use it for events and attractions such as weddings, artist installations, and car shows. During the COVID-19 quarantine, Carrie has even turned into a makeshift drive-in theater, where socially distanced people watch movies on a courtyard screen.

The Coatesville museum site is a hybrid of history and a “hot spot” active mill, since part of Lukens Steel Co. is still operating there. The museum — which focuses on the science of steelmaking more than the history — acquired the rest of the buildings, including houses.

Historical mills offer excellent learning opportunities for students on field trips, and for adult history buffs, Huston said.

Those mills that are renovated for commercial use, like in Bethlehem, can become economic engines for those regions.

“People want to go where history happened,” Huston said.