PI Perspective: How do we escape the conspiracy theory doom loop?

By Carmen Gentile

A right, a luxury, or a vital need?

~By FADOUA LOUDIY, COLUMN & PHOTOS

People all over the world crave freedom of speech. Some people give it all they have.

Without the freedom to express the truth, one becomes subservient to other people’s versions of the truth.

At the end of the day, America is still a democracy where the first rule of engagement is still free speech. In many countries, freedom of expression continues to be a pricey luxury that only the brave or the reckless, can afford, depending on one’s perspective.

Loudiy’s aunt, Saida, died at the age of 25 following a hunger strike. She was imprisoned in her native Morocco as a political detainee.

I grew up in Morocco, a country where the right to free speech is not sanctified in the constitution. While political matters have somewhat improved in the last 20 years, free speech is still not a birthright. Citizens, including journalists,continue to be harassed and jailed for expressing opinions that are deemed to question the political legitimacy of the monarchy, the state’s religion, or the country’s territorial integrity. In the early and mid-1970s, those were my father, my aunt and my uncle.

My father and uncle were the leaders of the largest leftist student organization (UNEM) at Mohammed V University in Rabat. My father was 23 and finishing his bachelor’s degree in sociology. In the 1970s student organizations in Moroccan universities were powerful political entities. The regime could not ignore their impact. Tall, strong, handsome, educated, articulate and charismatic, these two men were perceived as threatening to the state.

My uncle was arrested after the annual meeting of their party for questioning whether a contested territory belonged to Morocco. My father went to check on him and protest his arrest at the police station, unaware that my uncle had been released and that he, my father, was the one being hunted now. He was arrested as he walked in.

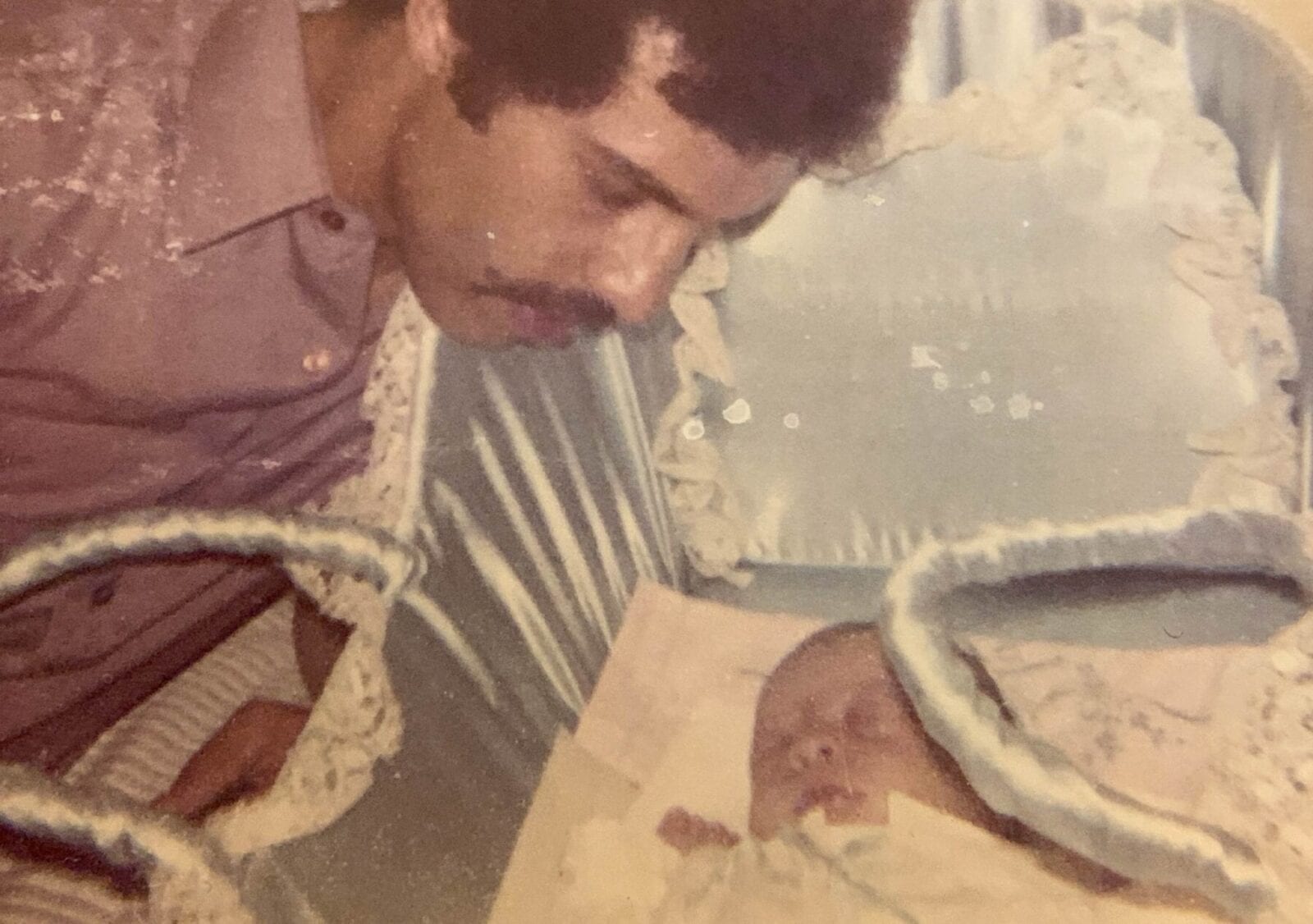

I was one month old and my mother was a medical student at the time. A year after his arrest my father was sentenced to 10 years in prison. For the first 10 years of my life, I saw him only behind bars. Occasionally, he and his friends would be taken to the hospital for a few days to get checked and my mother and I would have the luxury to see him in open space, without bars. Those times, drawing and playing with him in a hospital while he was wearing jail clothes, were perhaps the happiest of my childhood.

Loudiy as an infant with her father, who was imprisoned in their native Morocco for a decade because the government perceived him as a threat to the state.

After being initially released, my uncle was arrested again a few months later and released again. After months of secret detention and torture, he was released to await his trial. Having developed an illness as a result of his captivity, he escaped to France to seek medical attention.

He was sentenced to life in absentia, which meant he could not return to Morocco for 20 years. But the most tragic fate of all is my aunt, Saida. I was 5 when she died and, sadly, I only remember her funeral. But the book of poetry she wrote in prison was a fixture on my end table as a child. I re-read her poems a thousand times. Saida is my hero. She was kidnapped from her apartment after her boyfriend gave keys to the police after he was arrested.

While in jail, Saida asked to have the status of prisoner of conscience—meaning a person’s religious or political views don’t align with the government’ —which she and other political detainees were denied. She and her friends went on a hunger strike as a mode of protest.

She persisted, 34 days of a hunger strike, until her death. Even as my family pleaded, doctors refused to treat her, considering she was a traitor to the nation. She died alone at the age of 25 in 1977 in a cold hospital bed, with armed guards outside her room, while my family was hearing the beeping sounds of the heart monitor but could not see her nor touch her.

I often struggle to accurately express to my students how precious the freedom of expression they enjoy is. They are generally afraid to speak up, express their opinions, and articulate their truth to others, especially when it comes to politics.

Not surprisingly, this apprehension has increased exponentially in the last few years, even though it is not generated from practices of a repressive government.

Those who dare to express a truth that goes against the state’s narrative often do so at a cost. And yet, without people who find the courage or the folly to defy what some regimes define as red lines, the government would continue to destroy people’s livelihoods in total impunity.

Countless lives would fall into despair and, ultimately, into oblivion.

Fadoua Loudiy is the author of “Transitional Justice and Human Rights in Morocco: Negotiating the Years of Lead.” She also is a professor of communication at Slippery Rock University in Western Pennsylvania.

By Carmen Gentile

By Carmen Gentile

By Carmen Gentile

Welcome to Postindustrial, a multimedia company that’s redefining the Rust Belt on our own terms through stories, podcasts, and more. Sign up here for free updates!